Barn Owl

Introduction

The Barn Owl's endearing appearance and readiness to hunt in daylight has made this species one of Britain's most popular birds.

This species has a distinctively heart-shaped face, grey-buff wings and pure white underparts. It is most often seen when hunting in silent flight, low over vegetation, but it may also be seen perched on fence-posts. Barn Owl breeding success can fluctuate significantly in response to prey abundance; in 'good' small mammal years, large broods of six or more chicks can be raised, but when small mammal populations are low just one or two chicks may be reared.

British and Irish Barn Owls are sedentary throughout the year, with movements largely limited to the chick dispersal period. Sadly, collision with road or rail traffic is a frequently recorded cause of death among recoveries of ringed birds. The species is widespread across Britain & Ireland but absent from the far north and west of Scotland, upland areas and urban centres.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

Songs and Calls

Song:

Call:

Alarm call:

Flight call:

Begging call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

An early population estimate for 1932 of 12,000 breeding pairs in England and Wales concluded that there had been substantial decline over the previous 30-40 years (Blaker 1933, 1934). Decline continued through the 1950s and 1960s (Prestt 1965, Parslow 1973 ). The 1968-72 Atlas suggested a population of 4,500-9,000 pairs (Sharrock 1976 ) and the 1988-91 Atlas estimated a 37% loss of occupied 10-km squares in Britain since then (Gibbons et al. 1993 ). Project Barn Owl, organised jointly by BTO and Hawk and Owl Trust and carried out during 1995-97, estimated 4,000 pairs in the UK, Isle of Man and Channel Islands (Toms 1997, Toms et al. 2000, 2001). The potential for breeding numbers to double or halve over periods as short as 3-4 years, due to the cycles of vole abundance (Taylor et al. 1988), and to crash following severe winters (Altwegg et al. 2006), hampers the interpretation of such studies. The lack of detailed demographic data for this species was addressed by the BTO's Barn Owl Monitoring Programme (BOMP), which ran from 2000 to 2009 (Dadam et al. 2011).

Numbers of Barn Owls recorded via BBS have increased strongly since 1995 and reached a peak around 2009. As BBS is a diurnal survey, the detectability of primarily nocturnal species is low and could be influenced quite markedly by changes in behaviour: thus the trends should be interpreted with extra care. The number of nest records for Barn Owl has also increased rapidly over the same period, strengthening the evidence that a national population increase has indeed occurred since Project Barn Owl in 1995-97. There is likely to be some regional variation in population trends, however. RBBP provide a county breakdown of 2005 nesting totals here (Holling & RBBP 2008).

Though previously amber listed through its loss of UK range, the species was moved to the UK green list in 2015 (Eaton et al. 2015). Data from the BTO Nest Record Scheme show a large reduction in nest failures and an increase in fledglings per breeding attempt.

Distribution

Barn Owls are widely distributed in Britain, avoiding only high-altitude and urban areas and being absent from remoter islands, including the Outer Hebrides and Northern Isles. Densities appear to be highest in eastern England, although diurnal surveys are not ideal for monitoring abundance for owls. In Ireland the distribution is sparser, with highest densities in the southwest.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

Large range expansions are shown for both islands in winter. In Ireland these contradict known breeding population declines, and a matched breeding range contraction, and probably reflect changes in recording effort. In Scotland, gains could partly reflect improved coverage but include real gains probably facilitated by recent mild winters and conservation initiatives. A recent breeding range expansion in England likely reflects milder winters, conservation management such as nest box schemes and agri-environment schemes.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

Seasonality

Barn Owls are present throughout the year but reporting fluctuates, with increases during nest provisioning in summer, and in winter when birds can be seen hunting in daylight.

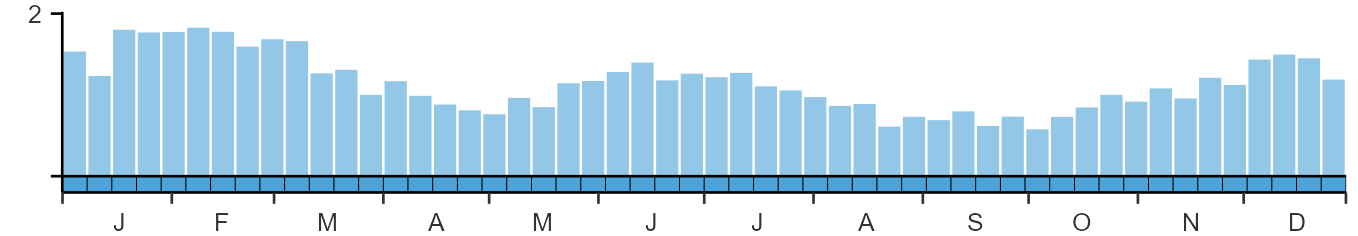

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Incubation

Fledging

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

lifespan

Survival of adults

Survival of juveniles

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Strigiformes

- Family: Tytonidae

- Scientific name: Tyto alba

- Authority: Scopoli, 1769

- BTO 2-letter code: BO

- BTO 5-letter code: BAROW

- Euring code number: 7350

Alternate species names

- Catalan: òliba

- Czech: sova pálená

- Danish: Slørugle

- Dutch: Kerkuil

- Estonian: loorkakk

- Finnish: tornipöllö

- French: Effraie des clochers

- Gaelic: Comhachag-bhàn

- German: Schleiereule

- Hungarian: gyöngybagoly

- Icelandic: Turnugla

- Irish: Scréachóg Reilige

- Italian: Barbagianni

- Latvian: plivurpuce

- Lithuanian: paprastoji liepsnotoji peleda

- Norwegian: Tårnugle

- Polish: plomykówka (zwyczajna)

- Portuguese: coruja-da-igreja / coruja-das-torres

- Slovak: plamienka driemavá

- Slovenian: pegasta sova

- Spanish: Lechuza común

- Swedish: tornuggla

- Welsh: Tylluan Wen

- English folkname(s): Yellow/White/Screech Owl, Billy Wix, Ginny Ollit

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

The use of toxic farm chemicals, loss of hunting habitat, increased disturbance, hard winters and the increase in traffic collisions have all been suggested as possible reasons for decline, but clear evidence is lacking. The upturn over recent decades has been aided by conservation measures including the widespread erection of nestboxes.

Further information on causes of change

Decline during the 1950s and 1960s was probably associated with use of toxic farm chemicals (especially organochlorine seed dressings), but also loss of hunting habitat, increased disturbance and the hard winters of 1946/47 and 1962/63 (Dobinson & Richards 1964, Percival 1990).

Causes of mortality potentially linked to the species' further decline include poisoning (Shawyer 1985) and collision with road traffic (Bourquin 1983, Massemin & Zorn 1998, Shawyer & Dixon 1999). Barn Owls are vulnerable to secondary poisoning from ingesting rodents killed by 'second-generation' rodenticides, which are used to control warfarin-resistant brown rats Rattus norvegicus (Shawyer 1985, 1987, Harrison 1990). Toxicological studies found that a small proportion of dead Barn Owls contained potentially lethal doses of rodenticide (Newton et al. 1991; Newton & Wyllie 1992a). There is no clear evidence, however, that links either poisoning or traffic collisions to population changes.

More recently, the erection of Barn Owl nestboxes, already numbering c. 25,000 by the mid 1990s, may have enabled the species to occupy areas (notably the Fens) that were previously devoid of nesting sites, and may have been a factor in improving nesting success (Dadam et al. 2011). In earlier decades, the plight of such a charismatic and popular bird led to extensive releasing of captive-bred birds in unguided attempts at restocking: by 1992, when licensing became a requirement for such schemes, it was estimated that between 2,000 and 3,000 birds were being released annually by about 600 operators, although many birds died quickly and never joined the nesting population (Balmer et al. 2000). There is some evidence, however, that releases might have aided population recovery (Meek et al. 2003).

The Barn Owl is a specialist predator of small mammals, in particular voles, mice, shrews and small rats (Shawyer 1998), but frogs and small birds are also taken (Bunn et al. 1982). The field vole Microtus agrestis, the most important prey of Barn Owls in mainland Britain (Glue 1974), favours grassy cover and a thick litter layer (Hansson 1977). In the UK, positive relationships were found between abundance of small mammals and sward height (Askew et al. 2007), whilst other authors have found a positive correlation between bank voles Clethrionomys glareolus and the width of grassy field margins (Shore et al. 2005). In Switzerland a similar result was found between unmown wildflower and herbaceous strips and densities of small mammals Aschwanden et al. (2007). Foraging of Barn Owl in an arable landscape is largely restricted to uncultivated or ungrazed field margins (Andries et al. 1994, Tome & Valkama 2001). It has been estimated that Barn Owls breeding in arable landscapes need about 35 km of rough grass margins within 2 km of the nest for the population to remain stable (Askew 2006).

Variation in adult survival contributes most to annual population changes (Robinson et al. 2014). Barn Owls experience reduced hunting opportunities in snowy or wet weather (Shawyer 1987). The recent downturn, after two decades of positive trend, may have resulted from a series of cold winters, during which higher-than-average numbers of individuals were reported dead (Clark 2011, Demog Blog). Poor hunting conditions in spring and summer may decrease adult or chick survival or reduce adult body condition, with associated lower investment in reproduction or, in some cases, the suspension of breeding (Shawyer 1987). Vegetation growth may also be affected by cold weather, with implications for the abundance or availability of small mammal prey (Shawyer 1987, Clark 2011).

Information about conservation actions

The ecological requirements for this species are reasonably well understood and therefore a number of conservation actions have been suggested, although the most important drivers of change are still uncertain.

Barn Owls take readily to nest boxes, and the increases in recent years are likely to have been aided by the widespread provision of boxes. Nest boxes can be a useful conservation tool in areas that are devoid of nesting sites (Dadam et al. 2011; Petty et al. 1994); however Klein et al. (2007) found that pairs nesting in boxes had lower productivity rates and recommended that partial reopening of buildings should be preferred if suitable buildings were available.

Provision of suitable habitat is also important and conservation actions and agri-environment policies that enable the provision of foraging habitat may also benefit Barn Owls. It has been estimated that Barn Owls breeding in arable landscapes need about 35 km of rough grass margins, 4-6 m wide, within 2 km of the nest sites for the population to remain stable (Askew 2006). Areas of rough grassland cut every 2-3 years supported more Barn Owl prey than areas cut annually though this was only significant for common shrews Sorex araneus (Askew et al. 2007). In Sussex, land cover was less heterogeneous at successful breeding sites, with home ranges characterised by a few habitat types of regular patch shapes; unsuccessful sites had significantly more improved grassland, suburban land and wetlands surrounding them (Bond et al. 2005).

Anticoagulant rodenticides (rat poisons) have been found in some Barn Owl carcasses in the UK, in most (but not all) cases at low concentrations which were unlikely to be considered a contributory cause of death (Walker et al. 2013, Walker et al. 2014). Nevertheless, precautions such as prompt removal and safe disposal of poisoned rates, as well as continued monitoring, would be prudent.

Publications (1)

Informing best practice for mitigation and enhancement measures for Barn Owls

Author: Henrietta Pringle, Gavin Siriwardena and Mike Toms

Published: 2017

Using the BTO’s ring-recovery database we have been able to analyse dispersal movements, with the aim of providing insight into Barn Owl movements in the UK. The results of this work suggest that new, high-quality habitat aimed at mitigating negative effects of HS2 on Barn Owls should be located between 3 km and 15 km away from the railway route, depending on the importance placed on minimising juvenile, as opposed to adult, mortality.

20.02.17

Reports