Black-winged Stilt

Introduction

This graceful long-legged wader used to be a rare passage visitor to Britain, but is now considered a colonising breeder.

With its striking black and white plumage, long bill, and red legs this species evokes the feeling of its Mediterranean home when it is found delicately wading through a lagoon, picking small insects off the water's surface.

Breeding was first recorded in 1945 (in Nottinghamshire) but we now see a handful of breeding attempts in most years, mostly in southern England, so this species could yet become an established breeder. The reasons for this are unclear, but warming temperatures and improved water quality in our wetlands probably contribute.

Key Stats

Identification

Songs and Calls

Call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Size

Population Change

The Black-winged Stilt first nested in the UK in 1983, and made only very occasional breeding attempts until 2014 (Ausden et al. 2016). There are encouraging recent signs that the species is in the process of colonising the UK and becoming a regular breeder,and 2019 was the sixth consecutive year that one or more breeding attempts were made (Eaton et al. 2021).

Distribution

Most Black-winged Stilts recorded in Britain & Ireland are in spring, comprising individuals and small groups. During 2008–11 such non-breeding birds were recorded in 24 10-km squares in southern Britain and two squares in Ireland. Some records related to pairs or trios, but where these did not remain for long, or the habitat was deemed unsuitable, no breeding evidence was assigned. Many records relate to the same nomadic individuals. Prior to the 2007–11 Atlas there had been six previous breeding attempts in Britain. In 2008 a seventh attempt took place, in Cheshire, but this was ultimately unsuccessful as all three chicks disappeared before fledging.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

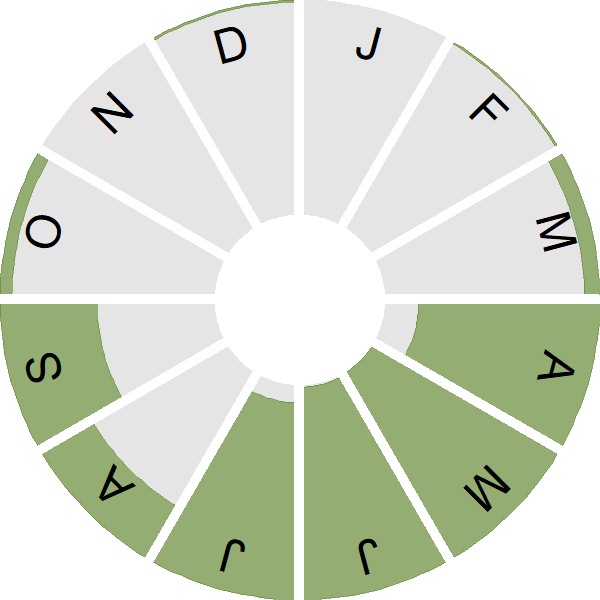

Seasonality

Black-winged Stilts are occasional spring overshoots and some birds attempt to breed.

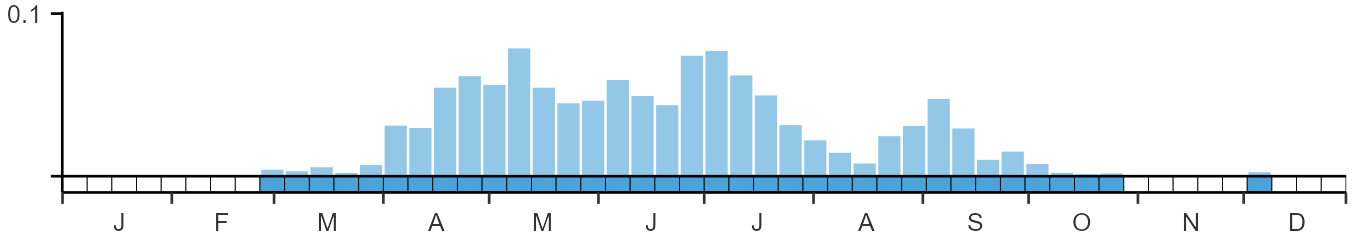

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Charadriiformes

- Family: Recurvirostridae

- Scientific name: Himantopus himantopus

- Authority: Linnaeus, 1758

- BTO 2-letter code: IT

- BTO 5-letter code: BLWST

- Euring code number: 4550

Alternate species names

- Catalan: cames llargues

- Czech: pisila cáponohá

- Danish: Stylteløber

- Dutch: Steltkluut

- Estonian: karkjalg

- Finnish: pitkäjalka

- French: Échasse blanche

- Gaelic: Fad-chasach

- German: Stelzenläufer

- Hungarian: gólyatöcs

- Icelandic: Háleggur

- Irish: Scodalach Dubheiteach

- Italian: Cavaliere d'Italia

- Latvian: garstilbis

- Lithuanian: baltasparnis kojukas

- Norwegian: Stylteløper

- Polish: szczudlak (zwyczajny)

- Portuguese: pernilongo

- Slovak: šišila bocianovitá

- Slovenian: polojnik

- Spanish: Cigüeñuela común

- Swedish: styltlöpare

- Welsh: Hirgoes Adeinddu

- English folkname(s): Longshanks

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

The occurrence of more regular breeding attempts in the UK follows increases in the nearest breeding populations. Climate change may be contributing to this range expansion and drought conditions are expected to occur more frequently in south-west Europe; however, habitat availability, predation and disturbance by humans are all threats that may affect the potential colonisation of the UK by this species (Ausden et al. 2016).