Carrion Crow

Introduction

This large, noisy, intelligent and inquisitive crow is widespread and familiar to many.

Carrion Crows are found throughout England and Wales, and most of Scotland apart from the far north-west, where this species is supplanted by its close relative, the Hooded Crow. On the island of Ireland, Carrion Crows occur only on the eastern fringes, while Hooded Crows are found throughout. In the areas where the two species overlap, including parts of Scotland, Northern Ireland and the Isle of Man, hybrids are found. In the UK, Carrion Crow numbers steadily rose from the early-1970s to the early-2000s, and have been fairly stable since. Carrion Crow numbers are controlled in some areas. The species is on the UK Green List.

The Carrion Crow's all-black plumage and bill sets it apart from the similar sized Hooded Crow and Rook. Unlike Rooks, Carrion Crows are more likely to be solitary, and their call sounds more assertive. Carrion Crows are omnivorous, taking grains, invertebrates, eggs, chicks, carrion and whatever else they can scavenge. They frequent almost all habitats, from uplands to gardens. Birds construct large nests, usually of twigs, and maintain a large breeding territory, producing one brood a year in the spring.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

ID Videos

This section features BTO training videos headlining this species, or featuring it as a potential confusion species.

Corvids

GBW: Jackdaw and Carrion Crow

Songs and Calls

Call:

Alarm call:

Flight call:

Begging call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

Carrion Crows have increased consistently since the 1960s (Gregory & Marchant 1996) although there are signs that the increase has slowed in recent years. Since 1995 the BBS has recorded ongoing shallow increase in England offset by stability (or minor decrease since 2000) in Scotland, with a fluctuating trend in Wales. The BBS map of change in relative density between 1994-96 and 2007-09 indicates that, despite strong increase in southeastern England and much of Scotland, there had been sharp decreases during that period in southwestern England, Wales, upland England and northeastern Scotland. Since 1968, nest failure rates have fallen steeply and laying date has advanced by eight days. There has been an increase among Carrion and Hooded Crows, taken together, across Europe since 1980 (PECBMS: PECBMS 2020a>).

Distribution

Carrion Crows are widely distributed throughout England, Wales, the Channel Islands and south and east Scotland. They are replaced by Hooded Crows in Ireland and western Scotland, including the Hebrides and Northern Isles. Densities are highest on low ground, with mixed and pastoral farmland, in southeast and central England into eastern Wales, the central lowlands of Scotland and northeast Scotland.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

There has been a 6% range expansion since the 1968–72 Breeding Atlas. Most gains were in western Scotland and Ireland, though many involve 10-km squares with only single birds and the occasional pair.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

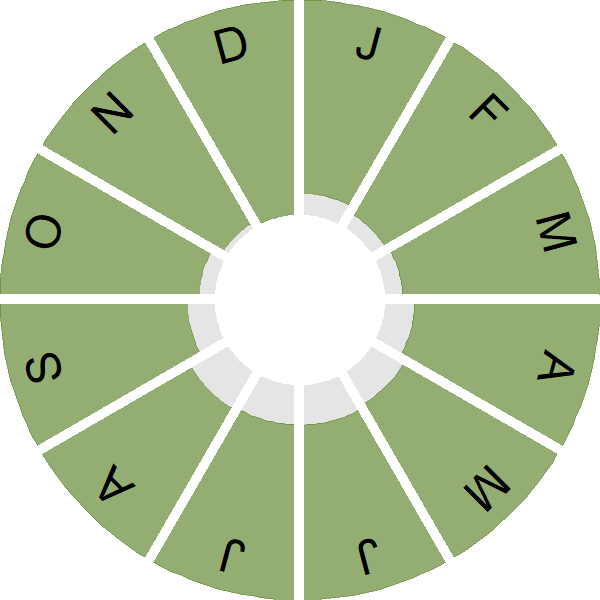

Seasonality

Carrion Crow is recorded throughout the year on up to 60% of complete lists.

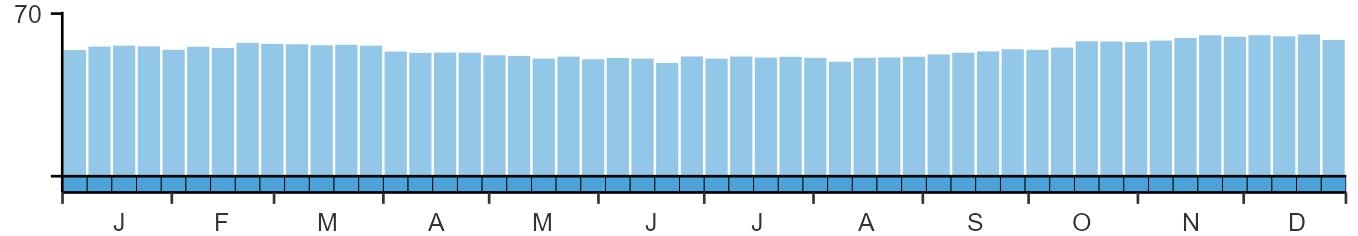

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

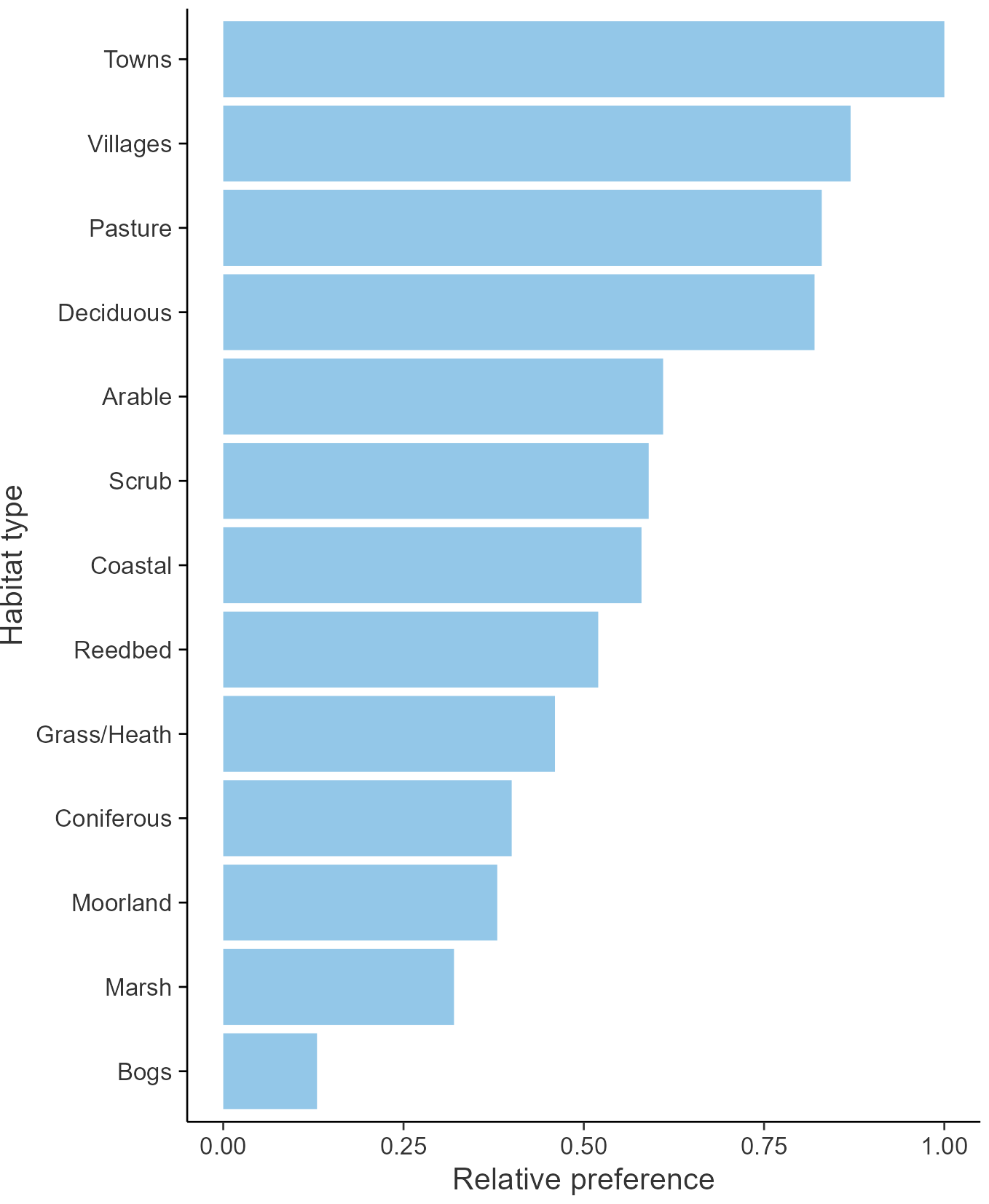

Habitats

Breeding season habitats

Relative frequency by habitat

The graph shows the habitats occupied in the breeding season, with the most utilised habitats shown at the top. Bars of similar size indicate the species is equally likely to be recorded in those habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Incubation

Fledging

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

lifespan

Survival of adults

Survival of juveniles

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Passeriformes

- Family: Corvidae

- Scientific name: Corvus corone

- Authority: Linnaeus, 1758

- BTO 2-letter code: C.

- BTO 5-letter code: CARCR

- Euring code number: 15671

Alternate species names

- Catalan: cornella negra

- Czech: vrána obecná

- Danish: Sortkrage

- Dutch: Zwarte Kraai

- Estonian: mustvares

- Finnish: varis

- French: Corneille noire

- Gaelic: Feannag-dhubh

- German: Rabenkrähe

- Hungarian: kormos varjú

- Icelandic: Svartkráka

- Irish: Caróg Liath/Caróg Dhubh

- Italian: Cornacchia nera

- Latvian: melna varna

- Lithuanian: juodoji varna

- Norwegian: Svartkråke

- Polish: czarnowron

- Portuguese: gralha-preta

- Slovak: vrana cierna

- Slovenian: crna vrana

- Spanish: Corneja negra

- Swedish: svartkråka

- Welsh: Brân Dyddyn

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

There are few specific studies providing evidence for the causes of the increase in this species, although evidence presented here shows that increases in breeding success have been important. Ecological causes of this could be increases in food availability and the increasing suitability of urban areas (driving the species' expansion there), although specific evidence supporting these hypotheses is limited.

Further information on causes of change

The demographic trends shown here reveal that there was a strong increase in the number of fledglings produced per breeding attempt between 1968 and the late 1990s, reflecting a decline in daily failure rate of nests at the egg and chick stages. Clutch size is currently at a similar level to 1968, but brood size has decreased. The number of fledglings per breeding attempt has dropped slightly since the late 1990s, perhaps due to density dependent effects. This suggests that the increase in Carrion Crow numbers is related to increases in breeding success although, as there are no estimates of survival, it is not possible to say what part this has played.

This species is omnivorous and highly adaptable and is thus able to exploit changing habitats and the ephemeral food resources in intensive agriculture, from ploughed fields to grazed pasture, allowing breeding pairs to hold territories year-round. It is also able to exploit the varied food sources found in towns and cities. Richner (1992) provided good evidence that food-supplemented pairs had a higher nesting success and produced more and heavier fledglings, demonstrating that food limitation can cause low fitness for individuals and thus could potentially restrict population-level reproductive success. In a local study, Yom-Tov (1974) showed that provision of excess food improved chick survival, and concluded that the distribution pattern of food was the ultimate factor limiting breeding success, perhaps because this affects levels of intraspecific nest predation. Although the impact on population size was not considered in these studies, it is possible that food availability for Carrion Crows has increased and so helped support the population increase. O'Connor & Shrubb (1986) suggest that the general increase in density of sheep in upland areas, and the increase in carrion resulting from this, may be responsible for the expansion of Carrion Crow populations, although evidence for this was not given and this is clearly not relevant to lowland areas (where sheep numbers have decreased).

A second hypothesis to explain this species' increase is that control by gamekeepers has reduced, but evidence supporting this is limited. Tharme et al. (2001) stated that the control of Carrion Crows by gamekeepers was the most probable cause of the low densities on grouse moors, although they found no significant relationship between the number of gamekeepers and Carrion Crow density. Furthermore, bag returns have shown no overall change in the number of Carrion Crows killed since 1961 (Tapper 1992, Tapper & France 1992).

Information about conservation actions

Numbers have increased consistently from at least the 1970s onwards, hence the Carrion Crow is not a species of concern and no conservation actions are currently required.

On the contrary, legal control of carrion crows occurs on many shooting estates, and crows have been suggested as possible drivers in the declines of other species. In some cases it is possible that crows can have local effects on breeding productivity of songbirds (Stoate & Szczur 2010), although it is uncertain whether they can also have population level effects and hence whether controlling crows would be an effective method to help to conserve songbird populations. In the case of waders, nesting success for three out of six waders (curlew, redshank and lapwing) was significantly higher when avian predators (both Carrion Crows and Common Gulls) were controlled in one study (Parr 1993). However, another moorland study found that control of predators (including Carrion Crows) was ineffective and that population trends of waders at a managed site were no different to comparable trends elsewhere (Calladine et al. 2014a).

Publications (1)

Watching Out for Waders: The Working for Waders Nest Camera Project

Author: Noyes, P., Laurie, P., Wetherhill, A. & Wilson, M.

Published: 2024

This report presents the results of a trial involving the use of trail cameras by land managers and other wader conservation stakeholders to monitor the outcome of wader nesting attempts. It presents the results of the trial and assesses the potential for the project to improve wader conservation knowledge and management.

04.10.24

Reports Research reports