Golden Plover

Introduction

The Golden Plover is arguably one of the most beautiful birds of upland Britain and its mournful fluty call in summer is evocative of wild places.

The spangled golden back gives this bird its name, set off by a rich black breast and belly in breeding plumage. During the summer months the Golden Plover is a bird of the uplands, from the Pennines north into Scotland, with a few pairs in Wales and western Ireland. Highest densities occur on Scottish islands, such as the Outer Hebrides and Shetland.

In winter, Golden Plovers can form large flocks anywhere in lowland Britain & Ireland, often mixing with Lapwings on farmland. Wetland Bird Survey records show the Humber Estuary, East Anglia and the Somerset Levels as areas where Golden Plovers are most plentiful.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

ID Videos

This section features BTO training videos headlining this species, or featuring it as a potential confusion species.

Grey & Golden Plovers

Songs and Calls

Song:

Call:

Alarm call:

Other:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

There was no annual monitoring of the breeding population before the inception of BBS. Since 1995, BBS shows stability in Scotland and in the UK as a whole. This is believed to follow an earlier decline (Gibbons et al. 1993). A detailed survey confirmed that a sharp decline has occurred in Wales since the 1980s, with just 36 pairs located in 2007 (Johnstone et al. 2008). Analysis of BBS data from 1994 and 2009, using land cover data, suggested the UK population may have increased slightly over this period, to 57,000-67,000 pairs in 2009 (Massimino et al. 2011). However, the report warns that sample sizes were very low in some regions, and subsequent BBS records suggest counts were unusually high in 2009, so this estimate should be treated with caution and it was not used in the latest update of UK population estimates (APEP4: Woodward et al. 2020).

Numbers across Europe have been broadly stable since 1981 (PECBMS: PECBMS 2020a>). Winter numbers counted by WeBS, although mainly at coastal sites and omitting some big concentrations inland, increased strongly in Britain between the mid 1980s and 2006, since when a sharp fall until around 2011 has been followed by fluctuations (Frost et al. 2020); these birds are mainly of Fennoscandian or Russian origin. The species has recently been on the amber list, because of the international importance of the UK's wintering population, but was returned to the green list in 2015 (Eaton et al. 2015).

Distribution

Golden Plover winter through most of the lowlands of Britain and the midlands and coastal regions of Ireland. They breed in the uplands of north and west Britain and Ireland. In Scotland, highest densities occur on the Outer Hebrides, Shetland and the flows of Caithness and Sutherland. Comparable densities still exist in parts of the English Pennines.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

One third of the Irish range and one fifth of the British range have been lost over the last 40 years. Losses have been greatest in the southern uplands of Scotland, and around the margins of the smaller outlying British and Irish populations, fragmenting them further.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

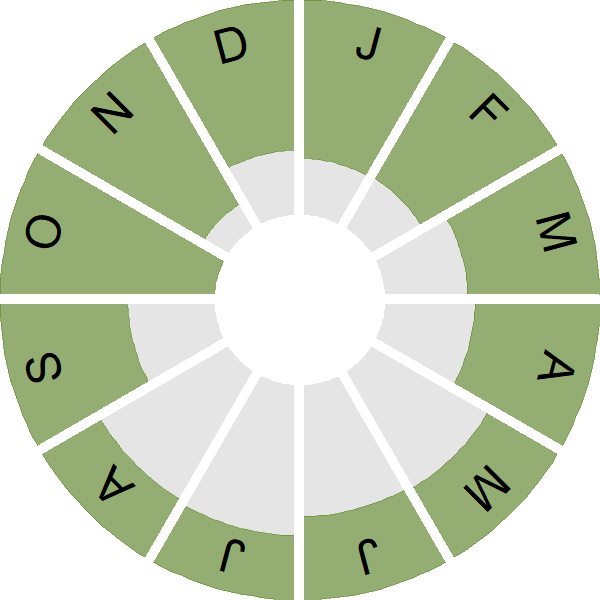

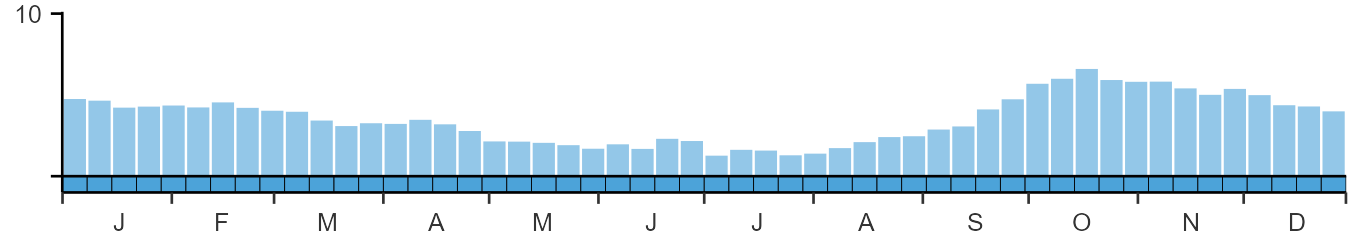

Seasonality

Golden Plovers are recorded throughout the year but with a noticeable peak during autumn migration when birds of northern and eastern origin arrive.

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

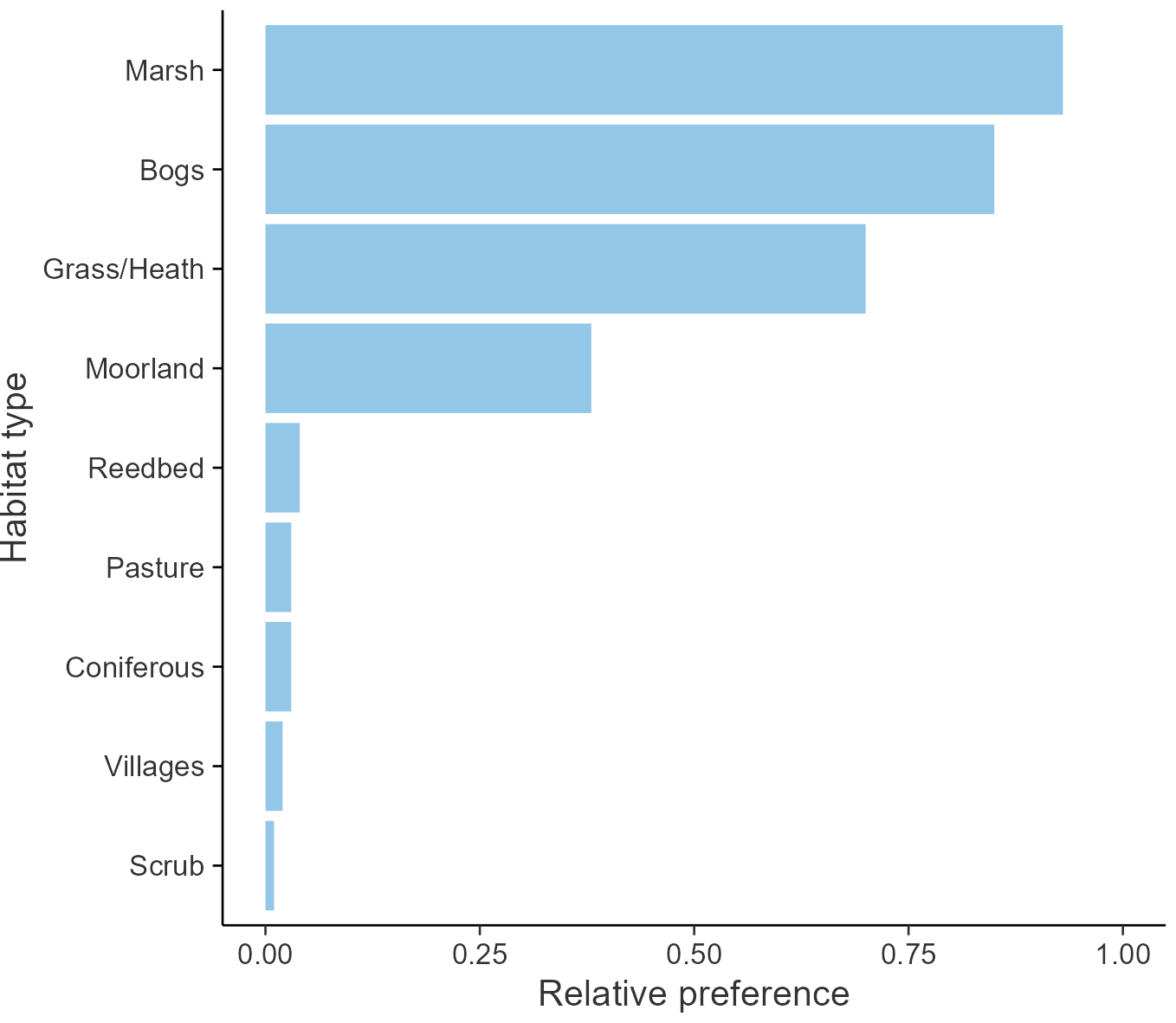

Habitats

Breeding season habitats

Relative frequency by habitat

The graph shows the habitats occupied in the breeding season, with the most utilised habitats shown at the top. Bars of similar size indicate the species is equally likely to be recorded in those habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

lifespan

Survival of adults

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Charadriiformes

- Family: Charadriidae

- Scientific name: Pluvialis apricaria

- Authority: Linnaeus, 1758

- BTO 2-letter code: GP

- BTO 5-letter code: GOLPL

- Euring code number: 4850

Alternate species names

- Catalan: daurada grossa

- Czech: kulík zlatý

- Danish: Hjejle

- Dutch: Goudplevier

- Estonian: rüüt

- Finnish: kapustarinta

- French: Pluvier doré

- German: Goldregenpfeifer

- Hungarian: aranylile

- Icelandic: Heiðlóa

- Irish: Feadóg Bhuí

- Italian: Piviere dorato

- Latvian: dzeltenais tartinš, sejas putns

- Lithuanian: dirvinis sejikas

- Norwegian: Heilo

- Polish: siewka zlota

- Portuguese: tarambola-dourada

- Slovak: kulík zlatý

- Slovenian: zlata prosenka

- Spanish: Chorlito dorado europeo

- Swedish: ljungpipare

- Welsh: Cwtiad Aur

- English folkname(s): Whistling / Hill Plover

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

The causes of change are unclear and demographic information is sparse.

Further information on causes of change

The causes of change are unclear and demographic information is sparse. Clutch size is unchanged, in spite of the fact that the records shown in the clutch size graph during 1996-98 include a large number of late-season nest records, with higher proportions of two- and three-egg clutches, which were submitted from an intensive study (J.W. Pearce-Higgins, pers. comm.).

A study alongside the Pennine Way indicates avoidance of areas heavily used by walkers and the potential for clearer definition of paths to increase habitat available to Golden Plovers (Finney et al. 2005). Nest survival on grass moors, unlike that on heather moors, may have declined over time (Crick 1992), perhaps linked to increased stocking densities of sheep (Fuller 1996), though other studies have found abundance was lower with reduced sheep densities (Douglas et al. 2017) or taller vegetation (Buchanan et al. 2017). A recent study found that high sheep tick load was negatively correlated with tick survival; however this was based on a low sample size at a single site, and further work is needed in order to verify this finding with a larger sample at more sites, and to ascertain whether tick load on chicks could be a potential driver of population trends (Douglas et al. 2019).

Warmer springs are reported to advance the breeding phenology of Golden Plovers and of their prey (Pearce-Higgins et al. 2005) and it is likely that the effects of climatic warming on cranefly (tipulid) populations will cause northward contraction of the species' range (Pearce-Higgins et al. 2010). Conservation management options in the light of climate change have been explored by Pearce-Higgins (2011). Abundance was also positively correlated with the level of predator control in one study (Buchanan et al. 2017).

Information about conservation actions

Although the drivers of change for this species remain poorly known, a number of potential conservation actions have been suggested. The species is found in upland habitats and requires patches of heather mixed with grass rather than larger stands of heather (Whittingham et al. 2001), in particular wetter areas with soft rush (Whittingham et al. 2001), or cotton grass and bare peat (Pearce-Higgins & Yalden 2004) to support chicks. Hence conservation efforts should focus on providing a mosaic habitat and identifying and maintaining patches used by golden plover. Site-based management actions which aim to increase cranefly (tipulid) populations and manipulate predation rates could help protect the species to some degree from the potential future effects of climate change (Pearce-Higgins 2011). Clearly defined paths across moorlands could decrease disturbance and hence mean that more habitat is effectively available to Golden Plovers (Finney et al. 2005), although low levels of disturbance will not necessarily cause habitat avoidance or affect reproductive success (Pearce-Higgins et al. 2007). Evidence about stocking densities is contradictory and further research may therefore be required before conservation actions can be suggested (see Causes of Change section).

Control of predators has also been suggested as a possible conservation action: A survey of 18 estates in northern England and south-east Scotland also concluded that predator control had positive effects on Golden Plover abundance, but found that these effects saturate at a relatively low level of control above which there were few benefits (Littlewood et al. 2019). The same study did not find any benefits to waders resulting from heather burning.

Publications (7)

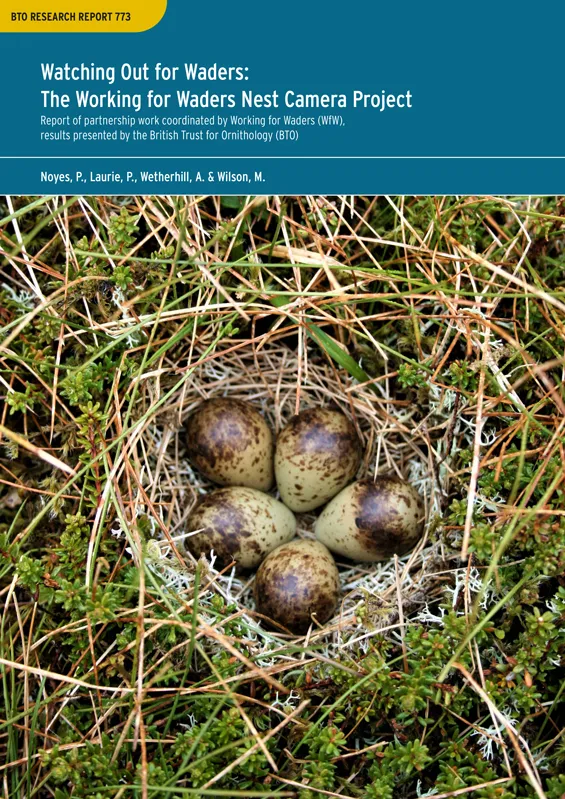

Watching Out for Waders: The Working for Waders Nest Camera Project

Author: Noyes, P., Laurie, P., Wetherhill, A. & Wilson, M.

Published: 2024

This report presents the results of a trial involving the use of trail cameras by land managers and other wader conservation stakeholders to monitor the outcome of wader nesting attempts. It presents the results of the trial and assesses the potential for the project to improve wader conservation knowledge and management.

04.10.24

Reports Research reports

Nesting dates of Moorland Birds in the English, Welsh and Scottish Uplands

Author: Wilson, M.W., Fletcher, K., Ludwig, S.C. & Leech, D.I.

Published: 2022

Rotational burning of vegetation is a common form of land management in UK upland habitats, and is restricted to the colder half of the year, with the time period during which burning may be carried out in upland areas varying between countries. In England and Scotland, this period runs from the 1st October to 15th April, but in the latter jurisdiction, permission can be granted to extend the burning season to 30th April. In Wales, this period runs from 1st October to 31st March.This report sets out timing of breeding information for upland birds in England, Scotland and Wales, to assess whether rotational burning poses a threat to populations of these species, and the extent to which any such threat varies in space and time.

17.02.22

Reports Research reports

Sensitivity mapping for breeding waders in Britain: towards producing zonal maps to guide wader conservation, forest expansion and other land-use changes. Report with specific data for Northumberland and north-east Cumbria

Author: O’Connell, P., Wilson, M., Wetherhill, A. & Calladine, J.

Published: 2021

Breeding waders in Britain are high profile species of conservation concern because of their declining populations and the international significance of some of their populations. Forest expansion is one of the most important, ongoing and large-scale changes in land use that can provide conservation and wider environmental benefits, but also adversely affect populations of breeding waders. We describe models to be used towards the development of tools to guide, inform and minimise conflict between wader conservation and forest expansion.Extensive data on breeding wader occurrence is typically available at spatial scales that are too coarse to best inform waderconservation and forestry stakeholders. Using statistical models (random forest regression trees) we model the predicted relative abundances of 10 species of breeding wader across Britain at 1-km square resolution. Bird data are taken from Bird Atlas 2007–11, which was a joint project between BTO, BirdWatch Ireland and the Scottish Ornithologists’ Club, and modelled with a range of environmental data sets.

09.12.21

Reports Research reports

Monitoring Breeding Waders in Wensleydale: trialling surveys carried out by farmers and gamekeepers

Author: Jarrett, D., Calladine, J., Wernham, C., Wilson, M.

Published: 2017

21.11.17

Reports

Consequences of population change for local abundance and site occupancy of wintering waterbirds

Author: Méndez, V., Gill, J.A., Alves, J.A., Burton, N.H.K. & Davies, R.G.

Published: 2017

Protected sites for birds are typically designated based on the site’s importance for the species that use it. For example, sites may be selected as Special Protection Areas (under the European Union Directive on the Conservation of Wild Birds) if they support more than 1% of a given national or international population of a species or an assemblage of over 20,000 waterbirds or seabirds. However, through the impacts of changing climates, habitat loss and invasive species, the way species use sites may change. As populations increase, abundance at existing sites may go up or new sites may be colonized. Similarly, as populations decrease, abundance at occupied sites may go down, or some sites may be abandoned. Determining how bird populations are spread across protected sites, and how changes in populations may affect this, is essential to making sure that they remain protected in the future.

20.09.17

Papers

Negative impact of wind energy development on a breeding shorebird assessed with a BACI study design

Author: Sansom, A., Pearce-Higgins, J.W. & Douglas, D.J.T.

Published: 2016

15.04.16

Papers

Distribution shifts in wintering Golden Plover Pluvialis apricaria and Lapwing Vanellus vanellus in Britain

Author: Gillings, S., Austin, G.E., Fuller, R.J. & Sutherland, W.J.

Published: 2006

01.01.06

Papers Bird Study