Grey Wagtail

Introduction

The Grey Wagtail, with its glowing, bobbing, bright yellow undertail can be found close to rivers and other waterbodies across Britain & Ireland.

Primarily a bird of fast flowing water the Grey Wagtail can also be seen along slower moving rivers and around the edges of lakes and ponds in our towns and cities, where its hunts aquatic insects. It is widespread in Britain & Ireland, but is found less on higher ground in the winter months.

Grey Wagtail is a partial migrant. As such, it can be affected by freezing conditions and during the autumn can be seen flying over migration watchpoints on the way to warmer climes further south, as far away as North Africa. Its UK population has fluctuated and the species is currently on the Amber List.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

ID Videos

This section features BTO training videos headlining this species, or featuring it as a potential confusion species.

Yellow-coloured wagtails

Songs and Calls

Song:

Call:

Flight call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

Grey Wagtails occur at highest densities along fast-flowing upland streams. WBS/WBBS shows a fluctuating population size along waterways, with a fall during the late 1970s and early 1980s from an initial high point in 1974, some increase since the late 1990s, and another steep drop around 2010. The BBS trend matches WBS/WBBS closely: there was an initial increase but from 2002 the trend was steeply downward, especially in Scotland. The species was moved from the green to the amber list in 2002, and subsequently from amber to the UK red list at the latest review in 2015 (Eaton et al. 2015). However, the long term decline is now categorised as moderate rather than steep, as a result of a slight upturn since around 2012.

The trends for Grey Wagtail are very similar to those for Pied Wagtail, suggesting that similar factors may be affecting these two species. Clutch and brood size of Grey Wagtails rose as the population fell, and are now getting smaller again. Nest failure rates have dropped substantially, and there has been linear increase in the number of fledglings per breeding attempt, suggesting that reduced survival is the likely driver of decline. Numbers across Europe have been broadly stable since 1980 (PECBMS: PECBMS 2020a>).

Distribution

In winter, Grey Wagtails are widespread throughout Britain except for parts of eastern England and the uplands. In Ireland, they are particularly widespread in the south and east. In spring breeding birds return to the British uplands, giving a distribution that is slightly more extensive than in winter; in Ireland the distribution remains largely unchanged. Densities are highest in the uplands, particularly in Wales, the Pennines and throughout mainland Scotland.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

The Grey Wagtail's breeding range has expanded by 19% since the 1968–72 Breeding Atlas, following gains in the East Midlands, East Anglia, Caithness and the Northern Isles. In winter there have been gains throughout the range, although most continuously in eastern England, on upland fringes and around the Scottish coast.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

Seasonality

Grey Wagtail is recorded throughout the year.

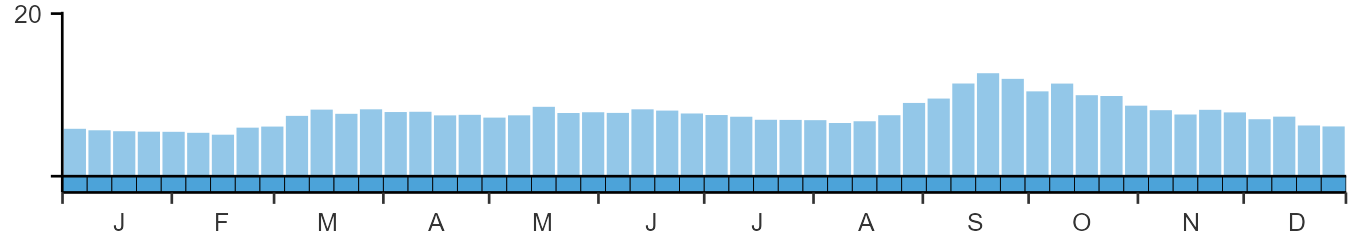

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

Habitats

Breeding season habitats

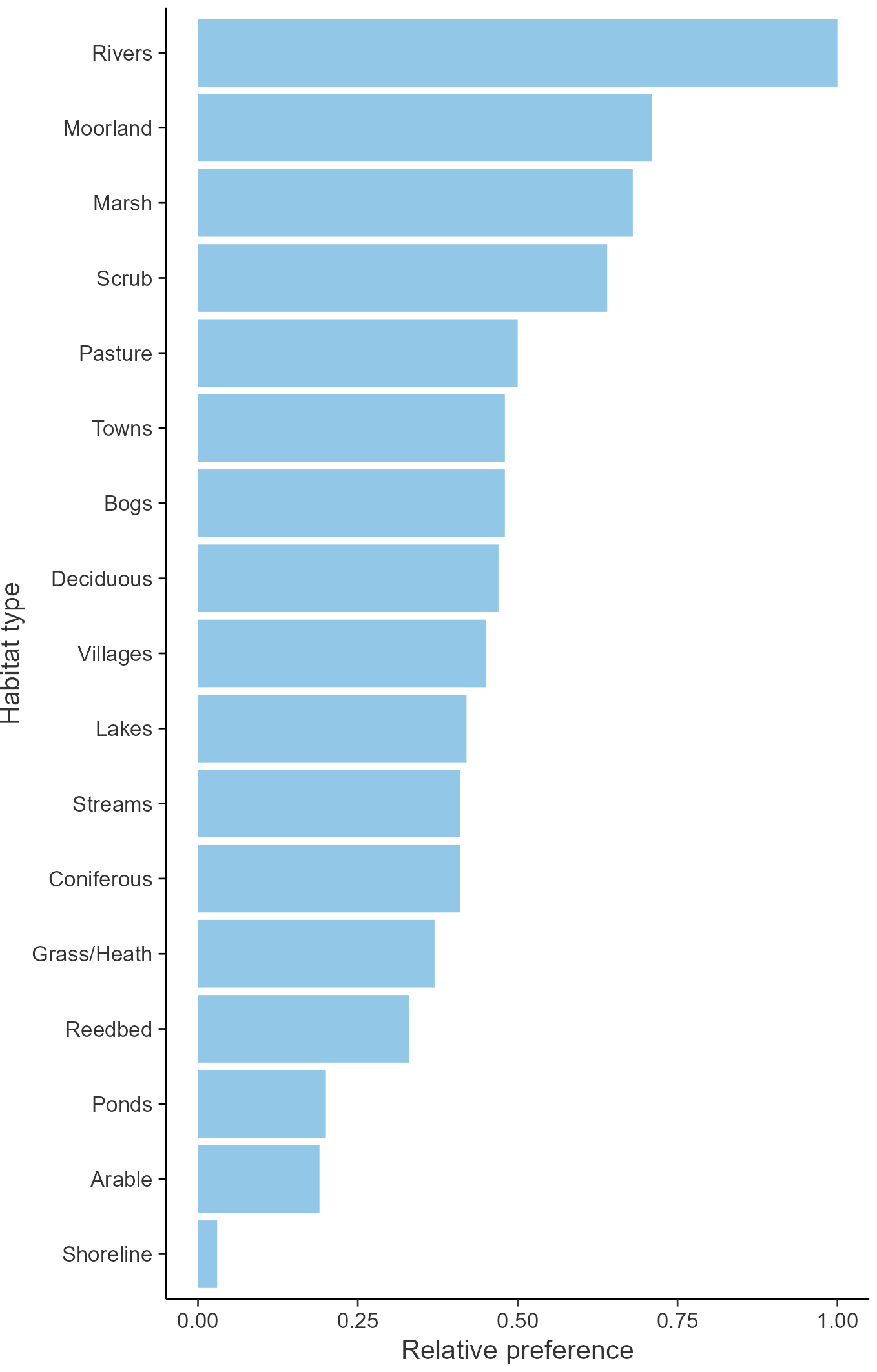

Relative frequency by habitat

The graph shows the habitats occupied in the breeding season, with the most utilised habitats shown at the top. Bars of similar size indicate the species is equally likely to be recorded in those habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Incubation

Fledging

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

lifespan

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Passeriformes

- Family: Motacillidae

- Scientific name: Motacilla cinerea

- Authority: Tunstall, 1771

- BTO 2-letter code: GL

- BTO 5-letter code: GREWA

- Euring code number: 10190

Alternate species names

- Catalan: cuereta torrentera

- Czech: konipas horský

- Danish: Bjergvipstjert

- Dutch: Grote Gele Kwikstaart

- Estonian: jõgivästrik

- Finnish: virtavästäräkki

- French: Bergeronnette des ruisseaux

- Gaelic: Breacan-baintighearna

- German: Gebirgsstelze

- Hungarian: hegyi billegeto

- Icelandic: Straumerla

- Irish: Glasóg Liath

- Italian: Ballerina gialla

- Latvian: peleka cielava

- Lithuanian: kalnine kiele

- Norwegian: Vintererle

- Polish: pliszka górska

- Portuguese: alvéola-cinzenta

- Slovak: trasochvost horský

- Slovenian: siva pastirica

- Spanish: Lavandera cascadeña

- Swedish: forsärla

- Welsh: Siglen Lwyd

- English folkname(s): Barley Bird

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

Causes of population decline and fluctuation may be related to survival rates of juveniles or adults. At present there are not enough data to investigate this idea and more targeted studies, for example RAS projects or analyses to relate survival to weather variables, are needed.

Further information on causes of change

Research has focused on the possible effects of water quality on this species. No correlation was found between Grey Wagtail breeding density and pH of streams in Scotland (Vickery 1991), a result supported by other authors who established that river acidity was less important than stream width, area of riffle and presence of bankside trees in influencing Grey Wagtail presence (Ormerod & Tyler 1987a). Laying date was three weeks later in acidic rivers than elsewhere in Wales, however, although clutch size, hatching success and brood size did not vary (Ormerod & Tyler 1991).

The species can feed in a range of habitats adjacent to rivers (Vickery 1991, Ormerod & Tyler 1987b) and do not rely on aquatic food sources (Ormerod & Tyler 1991): this may explain why they are less influenced by acidity of rivers, which has been associated with lower invertebrate abundance but not with Grey Wagtail abundance (Ormerod & Tyler 1991). Unhatched eggs collected over two years in Wales, Scotland and southwest Ireland did not contain toxic level of PCBs (Ormerod & Tyler 1992).

Causes of population decline and fluctuation appear to be related to survival rates. Targeted studies, for example RAS projects or analyses to relate survival to weather variables, have the potential to shed light on the population changes of this species.

Information about conservation actions

Numbers of Grey Wagtails have fluctuated but the causes of change are unclear and hence specific conservation actions which may benefit this species are uncertain. The presence of the species on rivers is influenced by stream width, area of riffle and presence of bankside trees rather than river acidity (Ormerod & Tyler 1987a), possibly because they do not rely only on aquatic food sources. Hence provision of suitable features along the river may be more important to attract Grey Wagtails than actions to improve water quality.