Greylag Goose

Introduction

One of our more common goose species, the large, orange-billed Greylag Goose can be found wherever there is water.

Britain & Ireland support two Greylag Goose populations, one of which is resident and one of which is made up of wintering birds. It is now impossible to separate our resident native population, which is located in north-west Scotland, from the naturalized birds that have their origin in domesticated flocks because the latter have greatly increased in numbers and range.

These birds are joined by migrant Greylags from Iceland, which winter across Scotland and Ireland, and small numbers of individuals from mainland Europe.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

Songs and Calls

Call:

Flight call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

Apart from an indigenous population in northwest Scotland and the Western Isles, and winter visitors mainly from Iceland, the Greylag Goose is a re-established species throughout the UK. Re-established Greylags increased very rapidly, at a rate estimated at 12% per annum in southern Britain between the 1988-91 Atlas period and 1999 (Rehfisch et al. 2002). This equates across Britain to 170%, or 9.4% per annum, in the period to 2000 (Austin et al. 2007). In Scotland, the native population has grown at an annual rate of 11.7% since 1997 and the re-established birds at 9.7% per annum since 1989 (Mitchell et al. 2011). It has become impossible to distinguish native from re-established populations and they are best now treated as a single unit (Mitchell et al. 2012). The WBS sample became large enough for annual monitoring in 1992, since when further steep increase has been recorded along linear waterways which has only recently began to show signs of levelling off. Annual breeding-season monitoring in a wider range of habitats through BBS has shown similar strong increases. Winter counts of resident birds have increased rapidly since the late 1960s (WeBS: Frost et al. 2020). Expanding populations of geese, including indigenous Scottish Greylag Geese, are creating a number of economic, social and environmental challenges and, increasingly, adaptive policies are required to manage native goose populations (Bainbridge 2017).

Distribution

It is evident from the winter distribution that the three populations that occur in Britain & Ireland in winter now overlap to such an extent that in many places it is impossible to separate resident native, re-established and Icelandic wintering birds. All favour low-lying agricultural land, though the early return of some birds to marginal upland breeding sites in February disrupts the pattern.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

The increase in range of the resident populations is clearly seen in the breeding distribution change map, which shows a 138% increase in range size since the 1988–91 Breeding Atlas.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

Seasonality

Greylag Geese are present year-round with winter populations supplemented by migrants.

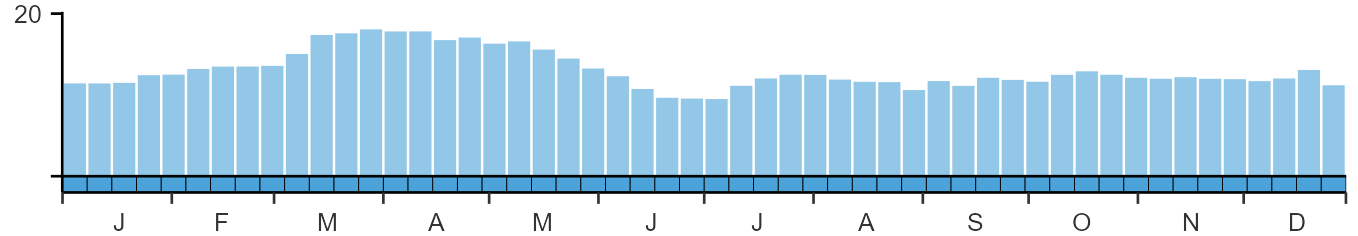

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

Habitats

Breeding season habitats

Relative frequency by habitat

The graph shows the habitats occupied in the breeding season, with the most utilised habitats shown at the top. Bars of similar size indicate the species is equally likely to be recorded in those habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

lifespan

Survival of adults

Survival of juveniles

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Anseriformes

- Family: Anatidae

- Scientific name: Anser anser

- Authority: Linnaeus, 1758

- BTO 2-letter code: GJ

- BTO 5-letter code: GREGO

- Euring code number: 1610

Alternate species names

- Catalan: oca comuna

- Czech: husa velká

- Danish: Grågås

- Dutch: Grauwe Gans

- Estonian: hallhani e. roohani

- Finnish: merihanhi

- French: Oie cendrée

- Gaelic: Gèadh-glas

- German: Graugans

- Hungarian: nyári lúd

- Icelandic: Grágæs

- Irish: Gé Ghlas

- Italian: Oca selvatica

- Latvian: meža zoss

- Lithuanian: pilkoji žasis

- Norwegian: Grågås

- Polish: gegawa

- Portuguese: ganso-bravo

- Slovak: hus divá

- Slovenian: siva gos

- Spanish: Ánsar común

- Swedish: grågås

- Welsh: Gwydd Lwyd

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

There is little good evidence available regarding the drivers of the breeding population increase in this species in the UK. However, the initial rapid increases following introduction may have been aided by lack of intraspecific competition and the ability of this species to exploit a previously unoccupied habitat, before density-dependent effects began to occur.

Further information on causes of change

No further information is available.

Information about conservation actions

The Greylag Goose is a re-introduced resident species across most of the UK, although native populations have persisted in north-west Scotland. Following successful conservation actions, including protection under the First Schedule of the Protection of Birds Act (1954) and grant-aided site management including re-sowing to improve foraging areas, the native breeding population has recovered (Mitchell et al. 2012). The introduced populations in the UK have increased rapidly. As a consequence, these two populations have merged and hence it is no longer practical to treat them, or wintering Icelandic birds, separately for conservation purposes (Mitchell et al. 2012). The situation is further complicated by the fact that non-native populations could potentially have an impact on populations of other native species.

Policies designed to protect feeding habitat for wintering geese, such as paying compensation to farmers for damage to crops (MacMillan et al. 2004; Fox & Madsen 2017) could have partly contributed to the population increases and continuation of such policies could hence enable ongoing protection. In the breeding season, a Danish study found that intermediate aged reedbeds (of between five and 11 years) supported the highest densities of nesting birds (Kristiansen 1998). Other actions to improve and create wetland habitats are also likely to help the species and provide suitable breeding habitat.

However, the population increases have led to increased conflict with landowners due to the effect of large numbers of geese on crops, and recent research has consequently focused on this conflict and on measures to regulate the numbers of geese at a sustainable level which takes both conservation and agricultural interests into account (MacMillan et al. 2004; MacMillan & Leader-Williams 2008; Fox & Madsen 2017). A Dutch study found that culling adult birds was more effective than egg pricking in reducing numbers (van Turnhout et al. 2010); however culling as a means of control can be controversial (Shirley 2010; Frith 2010).

A review of goose management policy in Scotland in 2010 recognised the success of previous policies but suggested that there may be a need to place more emphasis in some areas on minimising economic losses and ensuring that policies are cost-effective (Crabtree et al. 2010). NatureScot is now working with local management groups to test adaptive approaches to goose management in Scotland including sustainable culling.