Hen Harrier

Introduction

The beautiful, ghostly grey male and the brown, white-rumped female Hen Harrier are birds of wild places, upland moorland in the summer and coastal marshes during the winter.

As a breeding bird the Hen Harrier is affected by both persecution and land management decisions. Harriers feed mainly on voles and Meadow Pipits – which prefer grassland – and upland management for heather or forestry can exclude both the harrier and its prey.

During the winter months Hen Harriers form roosts at traditional sites, often close to favoured feeding areas, coming into roost from late afternoon through to dusk and leaving at first light.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

ID Videos

This section features BTO training videos headlining this species, or featuring it as a potential confusion species.

Harriers

Songs and Calls

Call:

Alarm call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

This species was red listed because of substantial declines over the last two centuries. However, the population increased in Scotland from the 1940s to at least the 1970s (Forrester et al. 2007). The UK population was unchanged between surveys in 1988-89 and 1998, with declines in Orkney and England but increases in Northern Ireland and the Isle of Man (Sim et al. 2001). A 41% increase was recorded in the UK and Isle of Man during 1998-2004, possibly due to increased use of non-moorland habitats, but with decreases in the Southern Uplands, east Highlands and England, all being areas with many managed grouse moors (Sim et al. 2007a). The 2010 survey estimated a total of 662 (576-770) pairs, a decline of around 18% since 2004: a notable decrease in Scotland might stem from habitat change and illegal persecution (Hayhow et al. 2013, Rebecca et al. 2016), while illegal persecution continues to limit harriers in England to very low levels of population (Hayhow et al. 2013). The most recent published survey was carried out in 2016, showing further declines across the four UK countries since 2010, and stability since 2010 on the Isle of Man (Wotton et al. 2018). There are renewed efforts currently to resolve the conflict between managed moorland and raptor conservation, amid public petitions and demonstrations against wildlife crime on grouse moors (Amar 2014, Elston et al. 2014, St John et al. 2018, Hodgson et al. 2019).

Further information about Hen Harrier populations can be found here.

Distribution

In Scotland, Hen Harriers breed in Orkney, the Uists and Inner Hebrides, parts of the Highlands and locally in the Southern Uplands. Smaller numbers are present in northern England, Wales and the Isle of Man. They are widely distributed in lowlands and upland fringes in winter.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

The breeding range had expanded in recent decades, especially in Wales., but there are marked losses elsewhere, including in southwest Scotland.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

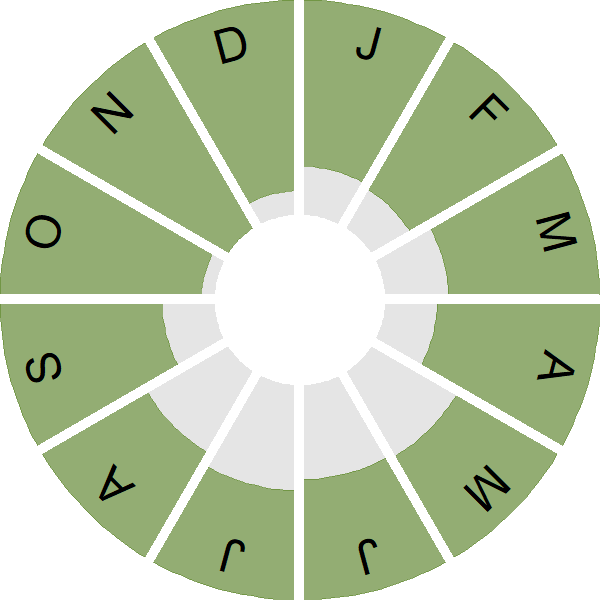

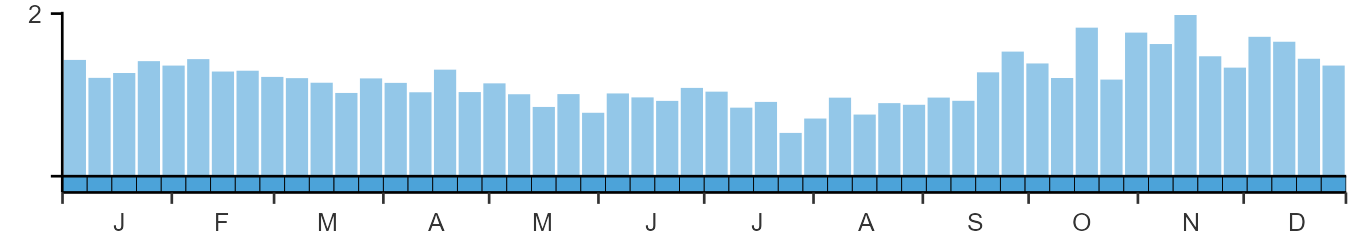

Seasonality

Hen Harriers are recorded year-round though in very different locations: uplands in the breeding season and lowlands and coasts in winter.

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Incubation

Fledging

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

lifespan

Survival of adults

Survival of juveniles

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Accipitriformes

- Family: Accipitridae

- Scientific name: Circus cyaneus

- Authority: Linnaeus, 1766

- BTO 2-letter code: HH

- BTO 5-letter code: HENHA

- Euring code number: 2610

Alternate species names

- Catalan: arpella pàl·lida comuna

- Czech: moták pilich

- Danish: Blå Kærhøg

- Dutch: Blauwe Kiekendief

- Estonian: välja-loorkull

- Finnish: sinisuohaukka

- French: Busard Saint-Martin

- Gaelic: Clamhan-nan-cearc

- German: Kornweihe

- Hungarian: kékes rétihéja

- Icelandic: Bláheiðir

- Irish: Cromán na Cearc

- Italian: Albanella reale

- Latvian: lauku lija

- Lithuanian: javine linge

- Norwegian: Myrhauk

- Polish: blotniak zbozowy

- Portuguese: tartaranhão-cinzento

- Slovak: kana sivá

- Slovenian: pepelasti lunj

- Spanish: Aguilucho pálido

- Swedish: blå kärrhök

- Welsh: Boda Tinwyn

- English folkname(s): Ringtail (f), Miller

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

Based on multiple field studies providing good evidence, the main driver of declines in Hen Harrier populations appears to have been illegal persecution, causing a reduction in nesting success, annual productivity and survival of breeding females.

Further information on causes of change

Demographic data presented here show that clutch size decreased between the late 1960s and the mid-1990s (although further investigation has shown that this trend was due to the increased proportions of records from Orkney, where clutch sizes tend to be smaller than on the mainland: Summers 1998, Crick 1998). Clutch size has increased again since the late 1990s, but is currently slightly lower than it was in the late 1960s.

There is good evidence showing that, although the Hen Harrier has been protected under UK law since 1961, many are still unlawfully killed or disturbed in efforts to protect the economic viability of driven shooting of Red Grouse (Redpath & Thirgood 1997, Thompson et al. 2009, 2016, Rebecca et al. 2016, Challis et al. 2018, Murgatroyd et al. 2019). A study combining Atlas data and a two-year field study provided good evidence that nesting success, annual productivity and survival of female Hen Harriers was lower on grouse moors than on other moorland or in young conifer forests, due to destruction by humans (Bibby & Etheridge 1993, Etheridge et al. 1997). Fielding et al. (2011) conclude that illegal killing is the biggest single factor affecting the species and that it is having a dramatic impact on the population in core areas of its range in northern England and Scotland. An expert knowledge assessment of threats across Europe also identified direct persecution as the main threat to breeding Hen Harriers in the UK (Fernandez-Bellon et al. 2020).

Management of moorland habitats, including keepering that remains within the law, however, can benefit harrier populations by increasing their prey and reducing their nest predators, especially crows and foxes, to which, as ground-nesters, they are sensitive (Baines & Richardson 2013, Ludwig et al. 2017, 2020a).

In areas where illegal persecution is minimal, food availability can restrict numbers. Habitat characteristics around harrier nest-sites (at a 1-km radius) can have a strong influence on breeding performance (Amar et al. 2002). Rough grass, a preferred habitat for field voles, is a critical foraging habitat for Orkney Hen Harriers (Amar & Redpath 2005, Amar et al. 2008a). On the Isle of Mull, nesting birds are associated with habitat mosaics which can include moorland, scrub and open forestry, and avoid grazed land (Geary et al. 2018) Research in Ireland suggests that breeding success is positively influenced by the extent of heath/shrub and bog habitat but negatively influenced by climatic instability and early season rainfall (Caravaggi et al. 2019a). Areas suitable for Hen Harriers in Ireland are strongly affected by anthropogenic activities including forestry, agriculture and recreational activities which can influence site occupation and breeding productivity (Caravaggi et al. 2019b).

Food shortage just before the laying period can result in low levels of polygyny and reduced nesting success among secondary females, resulting in reduced productivity (Amar & Redpath 2002, Amar et al. 2005). The area of rough grassland has decreased during the same period as sheep numbers have increased and this is thought have reduced food supplies (Amar et al. 2003, 2005, Amar & Redpath 2005), but there was no detectable effect of rough grass area on fledging success or fledged brood size (Amar et al. 2008). Further, these studies provide no evidence that the effects on breeding success have an impact on abundance.

However, Redpath et al. (2002a) present good evidence from a different field study in Scotland which also shows that food availability, notably numbers of field voles, can influence population change in Hen Harriers, where there is no persecution. Harrier densities were highest in areas and years where their small prey animals were most abundant. Clutch size was positively correlated with the number of field voles, although fledging success was not significantly correlated with the relative abundance of small prey (Redpath & Thirgood 1999, Redpath et al. 2002a). Madders (2000) also highlighted the importance of foraging habitat in Scotland, finding that the extent of young first-rotation forestry, the preferred foraging habitat in this area, is currently in decline and states that this has contributed to many of the reported changes in local Hen Harrier populations (although no specific research into demographic parameters were presented).

There is some evidence that climate also affects demography, although this is secondary to drivers outlined above and there is no evidence for effects on abundance. In Scotland, chick mortality increased in cold temperatures and annual values of harrier fledged brood size were positively related to summer temperature (Redpath et al. 2002b). Recovery of the Welsh harrier population until 2010, in contrast to those elsewhere in the UK, has been attributed to an increase in the breeding productivity, apparently due to a combination of cessation of human interference in recent years and warmer temperatures, leading to increased productivity (Whitfield et al. 2008). A 44% decline in Wales between 2010 and 2016 may have been caused by poor spring weather during that period, lack of prey availability and changes to upland management (Wotton et al. 2018).

A study in Ireland which investigated whether wind farms may have an effect on population trends found that the evidence for an impact was weak; the relationship between wind farm presence and population trends was negative but (marginally) non-significant and may not be causal (Wilson et al. 2017).

Information about conservation actions

The main driver which has caused declines and limited the recovery of the Hen Harrier in the UK is illegal persecution (Fielding et al. 2011), which affects both birds at their breeding sites and dispersing young birds. Therefore, stopping illegal killing is the most important action that can be taken to reverse declines. The confrontation between different stakeholders on moorland, in particular between grouse shooting interests and conservationists, remains a key area of conflict and movement towards a consensus will be important. Some observers have questioned the legitimacy of grouse shooting if it is only viable when birds of prey are killed (Thompson et al. 2009), whilst others contend that grouse shooting protects the conservation of heather moorland and populations of some declining birds such as waders that depend upon it (Sotherton et al. 2009). The final report of the Langholm Moor Demonstration project concluded that whilst some targets had been met, the project was unable to achieve compatibility for management between raptor and Red Grouse interests and grouse numbers remained insufficient to make driven shooting viable (LMDP Partners 2019).

A recent expert review of grouse moors commissioned by Scottish Government, suggested that, among other recommendations, grouse shooting in Scotland should be licensed if populations of Hen Harriers on and in the vicinity of grouse moors had not returned to favourable status within five years (Werritty et al. 2019).

In areas where illegal persecution does not occur, breeding productivity of Hen Harriers might be improved by habitat management: a mosaic including of moorland alongside foraging habitats such as rough grassland, heath/shrub, bogs or open forestry is preferred (Amar et al. 2008a; Geary et al. 2018; Caravaggi et al. 2019a), although habitat edges may represent an ecological trap (Sheridan et al. 2020). Increases in sheep grazing numbers may have led to decreases in prey (Amar et al. 2003) and hence reductions in grazing may also benefit Hen Harriers. Restricting forestry activity and avoiding recreational activity during the breeding season may reduce anthropogenic pressures (Caravaggi et al. 2019b). Keepering that remains within the law can also benefit harrier populations by increasing their prey and reducing levels of their nest predators, especially crows and foxes (e.g. Ludwig et al. 2017, 2020a).

Publications (2)

Assessment of recent Hen Harrier population trends in England through population modelling

Author: Macgregor, C.J., Pearce-Higgins, J.W., Siriwardena, G.M., Wilson, M.W. & Robinson, R.A.

Published: 2025

This study uses a population modelling approach to explore the effects of changes in rates of productivity, survival, and settlement on population growth in the English population of Hen Harriers.

14.03.25

Reports Research reports

Birds of Conservation Concern Wales 4: the population status of birds in Wales

Author: Johnstone, I.G., Hughes, J., Balmer, D.E., Brenchley, A., Facey, R.J., Lindley, P.J., Noble, D.G. & Taylor, R.C.

Published: 2022

The latest review of the conservation status of birds in Wales. The report assessed all 220 bird species which regularly occur in Wales. There are now 60 species of bird on the Red List, with 91 on the Amber List and just 69 - less than a third of the total number of species - on the Green List.

06.12.22

Reports Birds of Conservation Concern