Kestrel

Introduction

This small falcon is one of our most familiar and widely-distributed birds of prey, absent only from Shetland, parts of north-west Scotland and central Wales.

Kestrels prefer grassland habitats over which they can hunt for small mammals and small birds. A cavity nester, the species will also use suitable nest boxes, a behaviour that has enabled detailed study of their breeding ecology.

While still widely distributed, annual monitoring data have highlighted a decline in Kestrel numbers, the causes of which remain unclear. In some areas predation by Goshawks has been linked to the loss of local breeding pairs.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

ID Videos

This section features BTO training videos headlining this species, or featuring it as a potential confusion species.

Peregrine

Kestrel and Merlin

Hobby & Kestrel

Songs and Calls

Call:

Alarm call:

Other:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

Kestrels had recovered from the lethal and sublethal effects of organochlorine pesticides by the mid 1970s, the recovery probably driven by improving nesting success, but subsequently entered a steep decline in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Since the mid 1980s, the English population has fluctuated without a long-term trend being apparent but there are significant declines over the BBS period in England and especially in Scotland. The BBS map of change in relative density between 1994-96 and 2007-09 indicates that increase was widespread during that period, in contrast to the longer-term trend, but that decreases occurred in Northern Ireland, northwestern Scotland and in some English cities. There has been increase in the number of fledglings per breeding attempt. Despite its decline since the mid 1970s, the Kestrel breeds at high density in mixed farmland across much of England, suggesting that the British population might have exceeded 50,000 pairs (Clements 2008). A moderate decrease has been recorded in the Republic of Ireland since 1998 (Crowe 2012). There has been a decline across Europe since 1980 (PECBMS: PECBMS 2020a>).

In Scotland, the Scottish Raptor Monitoring Scheme is working to enhance coverage and is aiming to produce local study area trends for this species (Challis et al. 2018).

Distribution

Kestrels are widespread and abundant, being present in almost 90% of 10-km squares in both winter and the breeding season. Densities are highest in central and eastern England.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

A large population decline has been accompanied by a small breeding range contraction.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

Seasonality

Kestrels are present year-round.

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

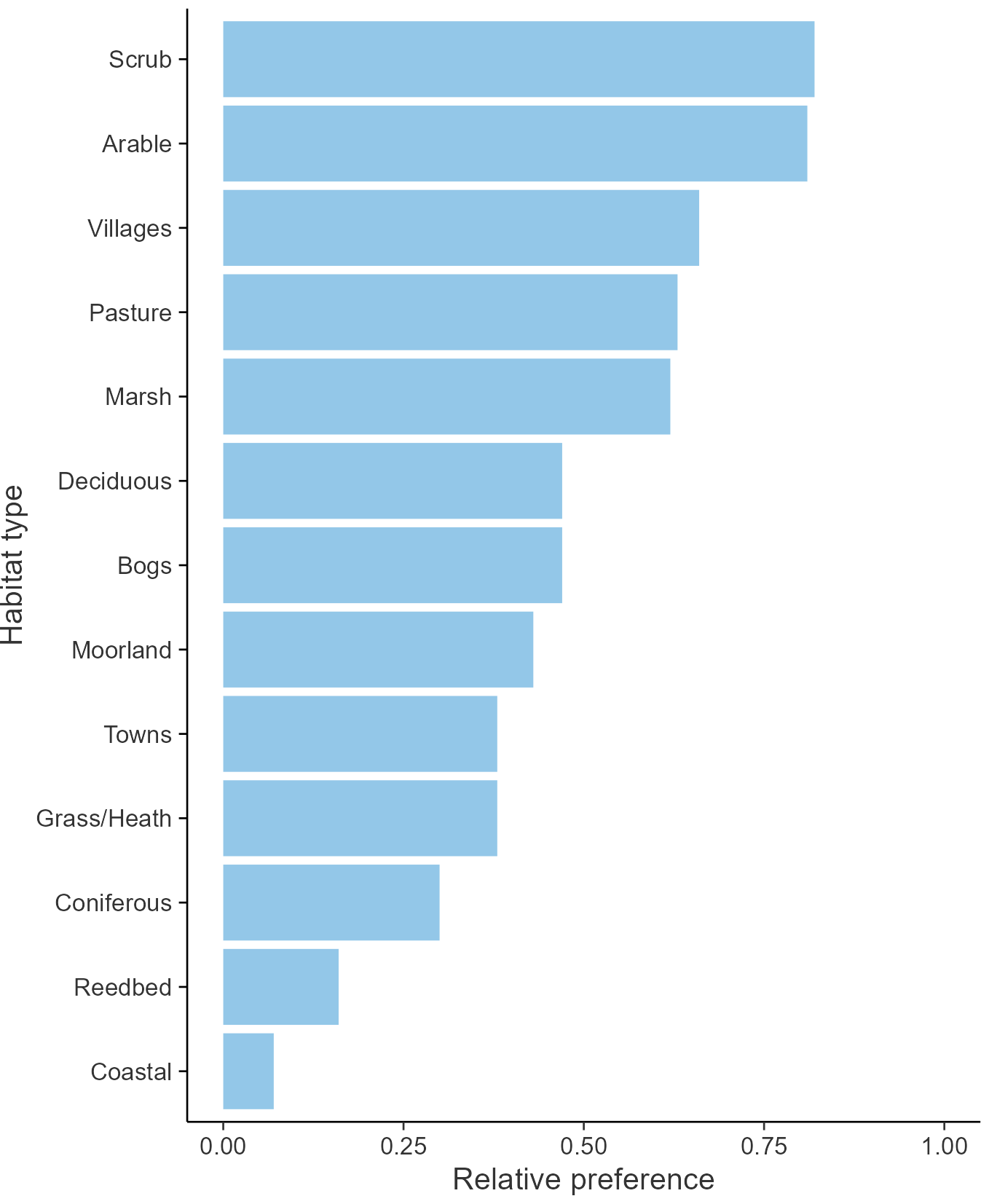

Habitats

Breeding season habitats

Relative frequency by habitat

The graph shows the habitats occupied in the breeding season, with the most utilised habitats shown at the top. Bars of similar size indicate the species is equally likely to be recorded in those habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Incubation

Fledging

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

lifespan

Survival of adults

Survival of juveniles

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Falconiformes

- Family: Falconidae

- Scientific name: Falco tinnunculus

- Authority: Linnaeus, 1758

- BTO 2-letter code: K.

- BTO 5-letter code: KESTR

- Euring code number: 3040

Alternate species names

- Catalan: xoriguer comú

- Czech: poštolka obecná

- Danish: Tårnfalk

- Dutch: Torenvalk

- Estonian: tuuletallaja

- Finnish: tuulihaukka

- French: Faucon crécerelle

- Gaelic: Speireag-ruadh

- German: Turmfalke

- Hungarian: vörös vércse

- Icelandic: Turnfálki

- Irish: Pocaire Gaoithe

- Italian: Gheppio

- Latvian: lauku piekuns

- Lithuanian: paprastasis pelesakalis

- Norwegian: Tårnfalk

- Polish: pustulka (zwyczajna)

- Portuguese: peneireiro-de-dorso-malhado / peneireiro

- Slovak: sokol myšiar (pustovka)

- Slovenian: postovka

- Spanish: Cernícalo vulgar

- Swedish: tornfalk

- Welsh: Cudyll Coch

- English folkname(s): Windhover

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

At present, the link between potential factors and the population trend of Kestrels has not been established and new research is needed. In the meantime, landowners keen to offer suitable Kestrel habitat should provide grassy cover for small mammals.

Further information on causes of change

The main period of decline in Britain occurred from the mid 1970s to the late 1980s and it has been linked to the effects of agricultural intensification on farmland habitats and their populations of small mammals (Gibbons et al. 1993), but it is interesting to notice that the number of nestlings fledged per breeding attempt had not declined, suggesting that, in areas retaining Kestrels, small mammals were not limiting fledging success. Integrated analyses suggest that changes in first-year and, particularly, adult survival are the primary contributors to population change (Robinson et al. 2014). Modelling suggests that climate change may have had a positive impact on the long-term trend for this species, resulting in less negative trends than would have occurred in the absence of climate change (Pearce-Higgins & Crick 2019).

Kestrels hunt a variety of prey, including voles, in particular in farmland settings (Shrubb 1993). Field voles Microtus agrestis favour habitats that can provide dense, grassy cover and a thick litter layer (Hansson 1977). Their population fluctuates in four-year cycles and it has been suggested that this might affect Kestrels that do not switch to other prey such as other small mammals, birds and insects (Shrubb 1993). There is no evidence, however, that Kestrels in the UK fluctuate alongside vole numbers. There is also, at present, no evidence that availability of nest sites limit population size of this raptor. A study over 23 years in a coniferous forest in northern England found a negative relationship between the numbers of Kestrels and Goshawks Accipiter gentilis, and remains of the smaller species near Goshawk nests (Petty et al. 2003). The impact of this larger raptor on population trend of Kestrels is not clear at the national level; however, it may be a factor at a local scale and more studies should focus on predation on Kestrels by other raptors.

Species high in the food chain are at risk of secondary poisoning, and birds of prey feeding on rodents are particularly vulnerable to anticoagulant rodenticides, but these are not the main cause of mortality of Kestrel in the UK (Walker et al. 2013) nor abroad (Christensen et al. 2012). A study on causes of death in raptors showed that the majority of Kestrels had died from collision and starvation (Newton et al. 1999). Carcasses reported for toxicology might be biased towards certain circumstances of death (eg collisions with vehicles) and could therefore underestimate the impact of rodenticides on Kestrel and other birds of prey. Targeted studies should be carried out, ideally to collect samples from live birds as well as dead ones.

Declining population of Kestrel is likely to be due to multiple factors. Changes in agricultural practice have reduced the habitat for its prey species, such as voles (although population trends of small mammals are not easy to establish (Flowerdew et al. 2004, Macdonald et al. 2007). Small rodents are abundant in road verges which provide suitable habitat for these mammals (Bellamy et al. 2000). In turn, Kestrel may be drawn to hunting along roads with increased risks of collision with passing vehicles, although there is no evidence for this at present. More research is needed to establish links between potential factors and Kestrel population change. In the meantime, landowners keen to offer suitable Kestrel habitat should provide grassy cover for small mammals.

Information about conservation actions

At present the link between potential factors and the population trend of Kestrel has not been established and new research is needed. In the meantime, landowners keen to offer suitable kestrel habitat should provide grassy cover for small mammals. Conservation policies can encourage the provision of suitable habitat at a landscape scale by enabling the take-up of agri-environment options such as buffer strips, uncultivated margins, conservation headlands and set-aside.

It should be noted, however, that kestrels do not use buffer strips or similar habitats directly but prefer to hunt over recently mown grassland adjacent to buffer strips where they can more easily catch mammals moving from the longer grass (Aschwanden et al. 2005; Garratt et al. 2011). Therefore, landowners (and agri-environment schemes) should aim to provide a mosaic which includes areas of recently cut grass adjacent to the mammal habitats.

Anticoagulant rodenticides (rat poisons) have been found in some Kestrel carcasses in the UK, with large concentrations found in some birds but no clear evidence that they were a contributory cause of death (Walker et al. 2013). Nevertheless, precautions such as prompt removal and safe disposal of poisoned rates, as well as continued monitoring, would be prudent.