Little Owl

Introduction

Our smallest owl, the Little Owl was introduced from Europe in the late 1800s, subsequently colonising England and parts of Wales.

This is a sedentary species, remaining in the same place summer and winter. Abundance maps from atlas studies reveal that Little Owls are most abundant in East Anglia, the Midlands and northern England. They prefer areas of mixed habitat with farmland, hedgerows and large, old trees with suitable nesting cavities.

Little Owl populations at the western edge of the English and Welsh range are declining, and it is thought that changes in agricultural practices may have reduced the availability of favoured invertebrate prey. Sometimes active during the daylight hours, Little Owls should be looked for on prominent perches in veteran trees, fence posts or roadside telegraph poles

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

Songs and Calls

Song:

Call:

Alarm call:

Flight call:

Begging call:

Other:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

The CBC/BBS trend for Little Owl in the UK shows very wide variation, but a downturn in recent decades suggests that a rapid decline now lies behind the observed fluctuations. Trends are uncertain, however, because the species has large breeding territories and, being largely inactive during the day, is difficult to detect except by dedicated surveys. A figure of c. 7,000 pairs from the BTO/Hawk & Owl Trust's Project Barn Owl (Toms et al. 2000) was the first replicable population estimate for Little Owls in the UK. Substantial further decrease has occurred subsequently.

Distribution

Little Owls were introduced to Britain in the late 1800s. Being largely sedentary, their breeding and winter distributions are very similar, being largely restricted to England and the Welsh borders, with isolated populations in northwest and coastal Wales. They are more abundant within East Anglia, the Midlands and central northern England than in the more westerly parts of the breeding range.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

In many parts of the range, population declines have been noted, leading to isolated losses and an 11% range contraction overall.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

Seasonality

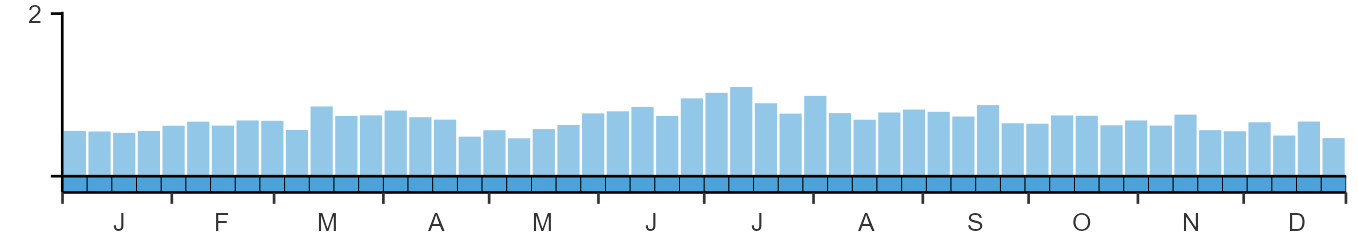

Little Owls are present throughout the year but not often recorded on daytime lists.

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

Habitats

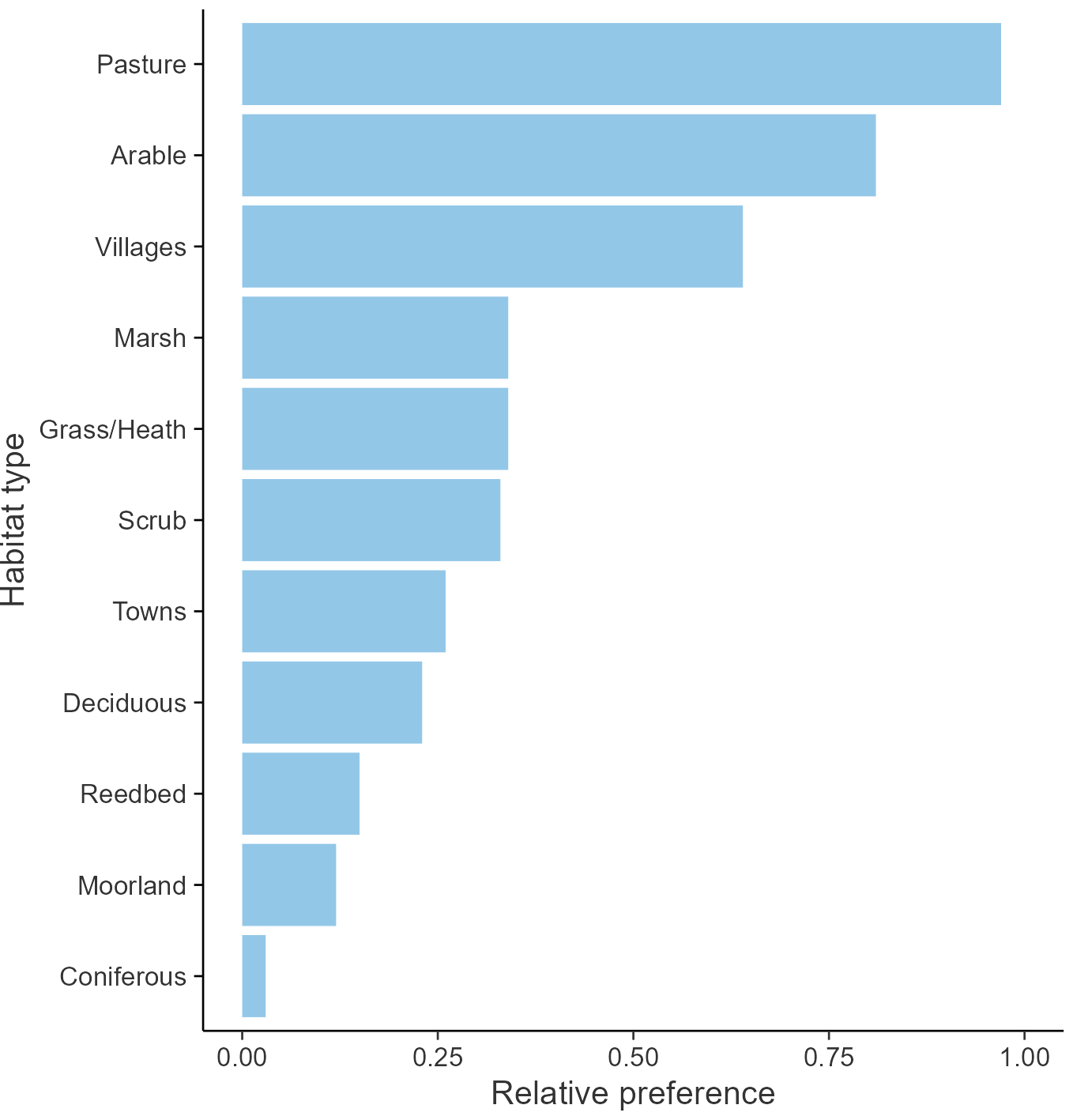

Breeding season habitats

Relative frequency by habitat

The graph shows the habitats occupied in the breeding season, with the most utilised habitats shown at the top. Bars of similar size indicate the species is equally likely to be recorded in those habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Incubation

Fledging

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

lifespan

Survival of adults

Survival of juveniles

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Strigiformes

- Family: Strigidae

- Scientific name: Athene noctua

- Authority: Scopoli, 1769

- BTO 2-letter code: LO

- BTO 5-letter code: LITOW

- Euring code number: 7570

Alternate species names

- Catalan: mussol comú

- Czech: sýcek obecný

- Danish: Kirkeugle

- Dutch: Steenuil

- Estonian: kivikakk

- Finnish: minervanpöllö

- French: Chevêche d’Athéna

- Gaelic: Comhachag-bheag

- German: Steinkauz

- Hungarian: kuvik

- Icelandic: Kattugla

- Irish: Ulchabhán Beag

- Italian: Civetta

- Latvian: majas apogs

- Lithuanian: paprastoji peledike

- Norwegian: Kirkeugle

- Polish: pójdzka (zwyczajna)

- Portuguese: mocho-galego

- Slovak: kuvik obycajný

- Slovenian: cuk

- Spanish: Mochuelo europeo

- Swedish: minervauggla

- Welsh: Tylluan Fach

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

There is little evidence available from the UK but studies from Europe suggest that the main demographic driver of declines in Little Owl is falling rates of juvenile survival. Circumstantial evidence suggests that this may be occurring due to loss of habitat and changes in farming practices.

Further information on causes of change

Modelling suggests that climate change may have had a negative impact on the long-term trend for this species (Pearce-Higgins & Crick 2019). Demographic trends, although based on a low sample size as few records are available, suggest that the decline is unlikely to be linked to failed nesting attempts, as all measures are unchanged or have increased, including the number of fledglings per breeding attempt (see above). There is very little evidence available from the UK regarding causes of the population decline. However, evidence from mainland Europe suggests that population changes are driven mainly by changes in survival. Le Gouar et al. (2011) analysed 35 years of ringing data from the Netherlands and found that juvenile survival rates decreased with time and that years when the population declined were associated with low juvenile survival. More than 60% of the variation in juvenile survival was explained by the increase in road traffic intensity or in average spring temperature. However, they state that these correlations reflect a gradual decrease in juvenile survival coinciding with long-term global change, rather than direct causal effects. The regular occurrence of years with poor adult survival (dry, cold years) was also important. In north-eastern France, Letty et al. (2001) also found that population dynamics were highly sensitive to adult and first-year survival and, in Switzerland and Southern Germany, Schaub et al. (2006) reported that variation of adult survival contributed most to variation of population growth rate while variation in fecundity contributed least. Thus, evidence from Europe at least suggests that changes in populations of Little Owl are largely due to changes outside of the breeding season (although note that survival can also be affected by breeding-season conditions).

However, in Denmark, Thorup et al. (2010) found, in a declining population, that first-year annual survival rates were much lower than values previously reported, but also that the mean number of fledglings per pair had declined. Measures of reproductive success were higher closer to important foraging habitats and were positively correlated with the amount of seasonally changing land cover (mostly farmland) around nests, as well as temperatures before and during the breeding season. Experimental food supplementation to breeding pairs increased the proportion of eggs that produced fledged chicks, suggesting that the main reason for the ongoing population decline is reduced productivity induced by energetic constraints after egg-laying.

In terms of ecological drivers, in Poland, there is anecdotal evidence that changes in the agricultural landscape associated with disappearance of traditional farming and management of grassland habitats were the main factors in the long-term population decline (Salek & Schropfer 2008). Zmihorski et al. (2006) concluded that the reduction in nesting sites and decreased food availability were the potential factors behind the Polish decline, although this evidence was circumstantial. In southern Germany, clutch size was affected by the availability of resources close to the nest site, and fledgling condition was negatively correlated with the size of the home range, suggesting the population is resource limited and that decreases in field and landscape heterogeneity may have reduced productivity (Michel et al. 2017). In another study in southern Germany, post-fledgling survival increased following supplementary feeding during the nestling stage and the first month after fledging, suggesting that resource limitations at this time may impact on juvenile survival rates and hence future recruitment to the breeding population (Perrig et al. 2017). Evidence from Spain has also suggested that habitat loss has played a role in population declines, due to increasing urbanisation (Martinez & Zuberogoitia 2004) and in Denmark the extent of contraction of Little Owl distribution varied across the country and local disappearance was associated with reduced areas of agricultural land (Thorup et al. 2010).

It is possible that some of the drivers identified in Europe may also be affecting the UK population, although this is not necessarily the case and, as mentioned above, evidence from the UK is sparse.

Information about conservation actions

As an introduced species, Little Owl does not have a conservation status in the UK and therefore conservation actions do not necessarily need to be considered for this species.

Evidence from Europe suggests that field and landscape heterogeneity may be important for this species and that restoring traditional mixed farming and management of grassland habitats may benefit Little Owl (Michel et al. 2017). Little Owls significantly preferred sparse and short sward grassland (especially pastures) where they can find ground-dwelling prey more easily. Conservation actions for Little Owls should therefore focus on providing and managing prey-rich grassland habitats (Salek & Lovy 2011).

Nest boxes are utilised by Little Owls. In Germany, these were more likely to be occupied if they were placed near orchards and in more open agricultural areas, further away from roads and forests (Gottschalk et al. 2011).

Publications (1)

Playback survey trial for the Little Owl Athene noctua in the UK

Author: Clewley, G.D., Norfolk, D.L., Leech, D.I. & Balmer, D.E.

Published: 2016

Little Owls are in decline in the UK, but are hard to monitor, making it difficult to establish this species' conservation and management needs. Newly-published research by the BTO demonstrates how playback could be an effective tool for helping to detect and monitor this species.

10.06.16

Papers Bird Study