Magpie

Introduction

With their iridescent black and white plumage, long tail and endless curiosity, Magpies are among our most distinctive birds. They feature prominently in folklore and superstition throughout Europe.

At least a third of the Magpie's 45 cm length is the long, stiff tail. In drab light, they are largely black, with white flanks, belly and wing patches. Their most distinctive call is a repetitive chac-chac-chac-chac', often made when birds are agitated. Captive birds have been shown to be capable mimics.

Magpies are common and widespread in most of Britain & Ireland apart from north and north-west of Scotland. They are scarce vagrants on a number of Scottish islands. They were formerly heavily persecuted throughout Britain, but their numbers grew through the late 20th century as this lessened. They are still controlled in many areas.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

Songs and Calls

Call:

Alarm call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

Magpies increased steadily until the late 1980s, after which abundance stabilised (Gregory & Marchant 1996). The BBS map of change in relative density between 1994-96 and 2007-09 indicates that increases occurred during that period in the central lowlands of Scotland, in London and in parts of the southeast, and decreases in Wales and the Peak District. The European trend is described as being a 'moderate decline'; however the trend graph suggests increases in the 1980s and early 1990s were reversed by decreases in the late 1990s, and the long-term change is calculated as +5% (PECBMS: PECBMS 2020a>).

Distribution

Magpies are widespread in both Ireland and Britain, being absent only from the northern half of Scotland and its islands. Highest densities are associated with urban and suburban areas from southeast England up through the Midlands to Lancashire and west Yorkshire.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

In recent decades, Magpies have colonised many upland areas of southern Scotland, as well as spreading into new areas of eastern Scotland and the fringes of the Highlands.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

Seasonality

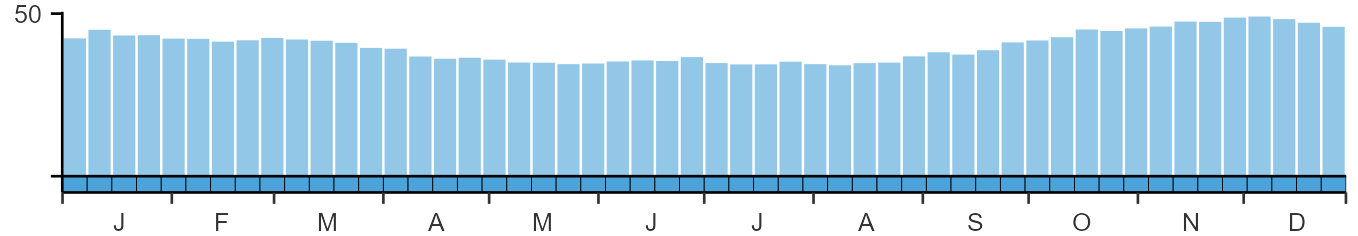

Magpie is recorded year round on up to 50% of complete lists.

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

Habitats

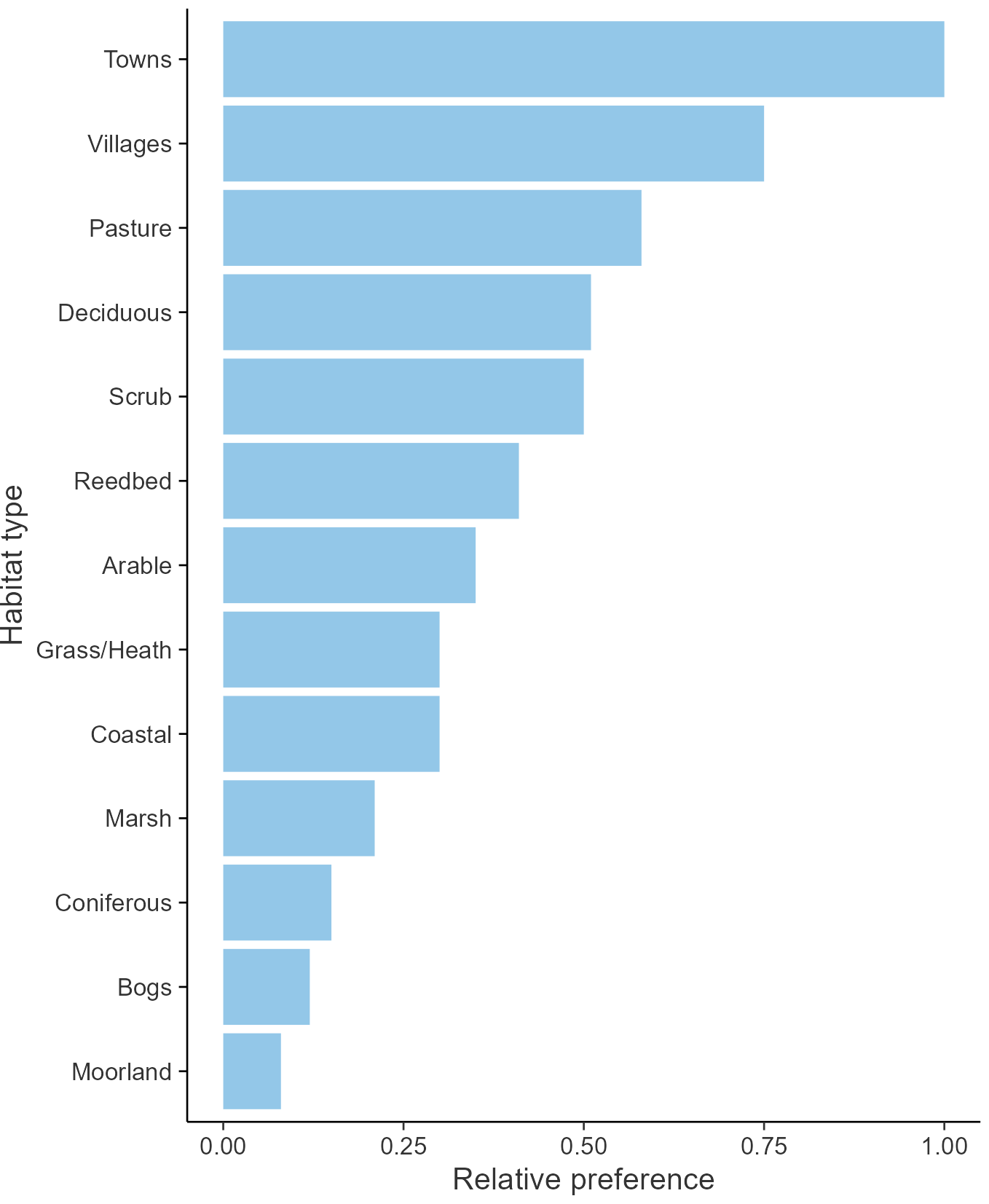

Breeding season habitats

Relative frequency by habitat

The graph shows the habitats occupied in the breeding season, with the most utilised habitats shown at the top. Bars of similar size indicate the species is equally likely to be recorded in those habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Incubation

Fledging

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

lifespan

Survival of adults

Survival of juveniles

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Passeriformes

- Family: Corvidae

- Scientific name: Pica pica

- Authority: Linnaeus, 1758

- BTO 2-letter code: MG

- BTO 5-letter code: MAGPI

- Euring code number: 15490

Alternate species names

- Catalan: garsa

- Czech: straka obecná

- Danish: Husskade

- Dutch: Ekster

- Estonian: harakas

- Finnish: harakka

- French: Pie bavarde

- Gaelic: Pioghaid

- German: Elster

- Hungarian: szarka

- Icelandic: Skjór

- Irish: Snag Breac

- Italian: Gazza

- Latvian: žagata

- Lithuanian: paprastoji šarka

- Norwegian: Skjære

- Polish: sroka (zwyczajna)

- Portuguese: pega

- Slovak: straka obycajná

- Slovenian: sraka

- Spanish: Urraca común

- Swedish: skata

- Welsh: Pioden

- English folkname(s): Chatterpie, Meg, Pianet

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

The number of fledglings per breeding attempt increased strongly until the 1990s but then stabilised, a pattern mirroring the population index, which suggests that changing breeding success has been an important driver of population change. There is little published evidence about the ecological drivers of change. Changes in control of Magpies could have played a role, but their generalist ecology means that they are able to prosper in suburban and intensively farmed landscapes, which is likely to have allowed populations to reach a historically high equilibrium level.

Further information on causes of change

Although there is little evidence directly supporting this, it is likely that the stabilisation in Magpie numbers reflects the population reaching carrying capacity in the intensively farmed and modern suburban landscapes. The fact that recent stability or decline is associated with parallel trends in fledglings per breeding attempt supports this. Demographic data presented here show that the number of fledglings per breeding attempt increased dramatically up until the 1990s but then stabilised (see above). Although clutch and brood sizes have declined over the whole time series, there have also been decreases in the failure of nests at the egg and chick stages. A strong trend towards earlier laying has also been identified and may be partly explained by recent climate change (Crick & Sparks 1999).

The historical increases in Magpies have occurred at the same time as falling levels of control by gamekeepers from the time of the First World War (Tapper 1992), but there is no direct evidence for a causal link. Since 1990, the widespread adoption of the Larsen trap for predator control has been responsible for a large increase in Magpie numbers killed on shooting estates (GWCT data), and this could have played a role in stabilising population growth in some areas, but is unlikely to explain population change in towns and cities.

Magpies have increased in farmland and woodland habitats, with the largest population growth on mixed and pastoral farms, and the smallest on arable land (Gregory & Marchant 1996). The remarkable adaptability of Magpies has enabled them to colonise many new urban and suburban localities since the 1960s.

Information about conservation actions

Numbers are currently stable following increases during the 1970s and 1980s, hence the Magpie is not a species of concern and no conservation actions are currently required.

On the contrary, legal control of magpies occurs on many shooting estates, and Magpies (along with Crows) have been suggested as possible drivers in the declines of other species. In the case of songbirds, there is evidence that predation of eggs and young does not have population level effects on songbirds and therefore wider control measures would not be appropriate for this purpose (Gooch et al. 1991; Newson et al. 2010b).