Nightingale

Introduction

Many people have heard of Nightingales, but how many people in this day and age have actually encountered them?

Thanks to its almost legendary song, references to the Nightingale pepper our culture. However, this species is declining in both numbers and range, and is now only found in a small area of southern and eastern England during the breeding season. The reasons for this decline are thought to encompass the degradation and loss of the scrubby woodland habitat upon which Nightingales depend to breed, including by browsing deer.

Tracking and ringing studies have taught us that Nightingales winter in the humid zone of West Africa, and arrive back in the UK to breed in April. Males sing at night until paired up, after which time their famous song is limited to dusk and dawn. Females lay one to two clutches a year, before birds depart for Africa in late summer. Nightingales are secretive, with cryptic brown plumage, meaning their song is definitely the best way to find them.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

ID Videos

This section features BTO training videos headlining this species, or featuring it as a potential confusion species.

Nightingale and Other Night Singers

Songs and Calls

Song:

Call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

The national survey of Nightingales organised by BTO in 1999 estimated the population at 6,700 (5,600-9,400) males, a marked range contraction since the previous survey in 1980, but only an 8% overall population decline (Wilson et al. 2002. Atlas surveys in 2008-11 found a 43% reduction in occupied 10-km squares since 1968-72, with withdrawal especially from western parts of the range (Balmer et al. 2013). Results from the most recent Nightingale Survey across Britain in 2012-13 indicated that further decrease has occurred since 1999, with 12 population estimates ranging from 5,094 to 5,938 territorial males (Hewson et al. 2017). Unlike previous estimates, the 2012-13 estimates also accounted for detectability, so the decline since 1999 is believed to be higher than the figures suggest. In 1976, over 71% of males were associated with woodland, especially coppice and young plantations, but by 2012 this had decreased to 37% and 55% of territories were then in scrub (Hayhow et al. 2015).

Despite small and decreasing samples, it has proved possible to calculate a meaningful CBC/BBS trend. This evidence has been sufficient to upgrade the status of Nightingale from amber to the red list of Birds of Conservation Concern in 2015 (Eaton et al. 2015). Though samples are too small to continue presenting a trend, CES suggested a sharp decline in productivity during the 1980s, perhaps because Nightingale nesting success may be adversely affected by cold and wet springs. It is among a suite of species that winter in the humid zone of West Africa and correspondingly are showing the strongest population declines among our migrant species (Ockendon et al. 2012, 2014). There has been a decline across Europe since 1980, although numbers have been relatively stable since c.1985 (PECBMS: PECBMS 2020a>); this overall trend masks a stark contrast between severe decreases in southern and western Europe and increases in the east of the range (PECBMS 2007).

Distribution

England represents the northern edge of the global breeding range of the Nightingale. Breeding is confined to an area south of a line from the Severn to the Humber, although an ongoing range contraction sees the range shrinking towards the southeastern strongholds of Kent, Sussex and Essex. These three counties, together with Hampshire, held the highest densities, whereas counties at the range edge are increasingly characterised by a small number of sites of relatively high population density. Such sites become increasingly isolated as birds disappear from surrounding countryside.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

The range contraction and fragmentation means the range size in 2008–11 was 43% smaller than in 1968–72.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

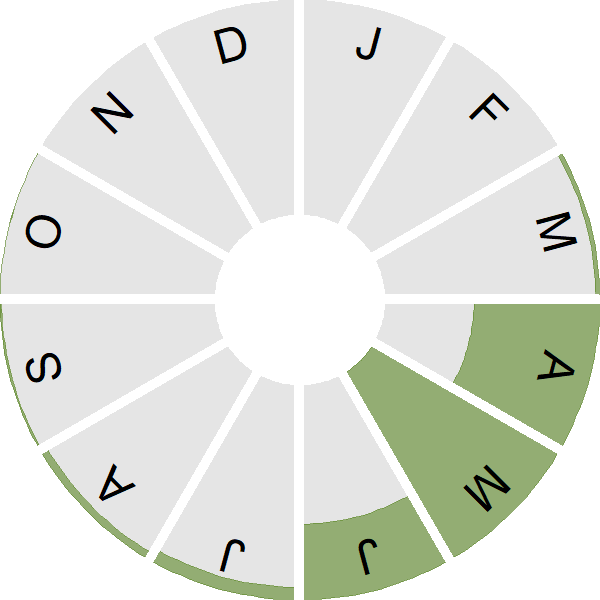

Seasonality

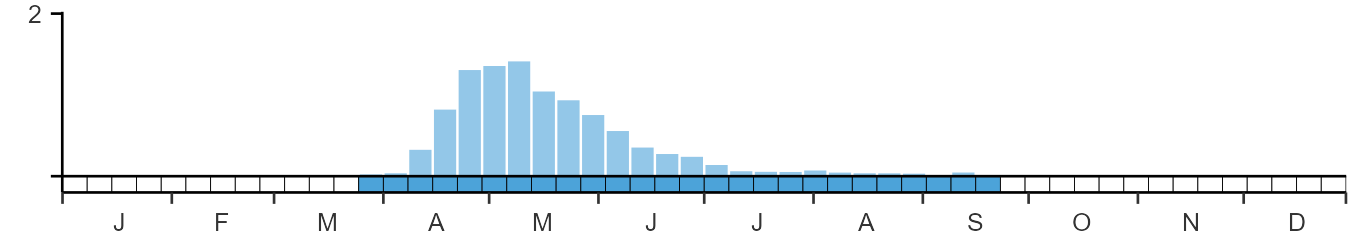

Nightingale is a localised and declining summer visitor, arriving from mid April onwards; records decline after song output drops though birds may be present through summer and are occasionally recorded during autumn migration.

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Incubation

Fledging

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

lifespan

Survival of adults

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Passeriformes

- Family: Muscicapidae

- Scientific name: Luscinia megarhynchos

- Authority: CL Brehm, 1831

- BTO 2-letter code: N.

- BTO 5-letter code: NIGAL

- Euring code number: 11040

Alternate species names

- Catalan: rossinyol comú

- Czech: slavík obecný

- Danish: Sydlig Nattergal

- Dutch: Nachtegaal

- Estonian: lõunaööbik

- Finnish: etelänsatakieli

- French: Rossignol philomèle

- Gaelic: Seiniolach

- German: Nachtigall

- Hungarian: fülemüle

- Icelandic: Næturgali

- Irish: Filiméala

- Italian: Usignolo

- Latvian: rietumu lakstigala

- Lithuanian: vakarine lakštingala

- Norwegian: Sørnattergal

- Polish: slowik rdzawy

- Portuguese: rouxinol

- Slovak: slávik obycajný

- Slovenian: slavec

- Spanish: Ruiseñor común

- Swedish: sydnäktergal

- Welsh: Eos

- English folkname(s): Barley Bird

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

There is strong evidence that deer grazing is having a negative effect on Nightingale numbers. Conditions on the wintering grounds, such as changes in habitat, are also likely to have carry-over effects into the breeding season. Several studies have highlighted the benefit of habitat management for this species, involving coppicing and control of deer numbers to promote the heterogeneous vegetation structure that Nightingales need.

Further information on causes of change

Several hypotheses have been put forward to explain Nightingale decline and are the subject of ongoing BTO research: these include reduction in coppicing, maturing of scrubland and conifer plantation, an increase in deer and their browsing pressure, higher predation pressure, reduced food quality, pressures on migration and deterioration of conditions on the wintering grounds (Fuller et al. 1999, 2005). Wintering habitat of British birds is being investigated by fitting geolocators to Nightingales (Holt et al. 2012b). Habitat deterioration on the wintering grounds may result in greater winter mortality or in birds arriving on the breeding grounds in poor condition (Ockendon et al. 2012). The potential roles of predation and reduced food quality have been little studied (Holt et al. 2012b). There is strong evidence, however, that increased browsing by deer has had a negative effect on Nightingale numbers.

Nesting Nightingales typically require closed-canopy scrub or young woodland, with bare ground under the canopy for feeding, but also area of low thick vegetation, generally associated with secondary succession and early regeneration after coppicing (Hewson et al. 2005, Wilson et al. 2005b). Canopy height in territories occupied by Nightingales is usually less than four metres in height (Wilson et al. 2005b). A study based in Cambridgeshire found that territory distribution peaked on areas where scrub height varied between three and five metres (Holt et al. 2012c). Nests are built on or close to the ground, in a thick field layer that will provide cover for nests and a refuge for newly fledged young. Scrub structure seems more important than its species composition, and the ideal habitat is probably a dome of increasing vegetation heights, with a crown of vegetation dense enough at the centre to create bare ground underneath, and a gradient of ground-cover towards the edges where the species can nest (Wilson et al. 2005b).

The structural diversity of woodland can be readily reduced by suspending coppicing and rotational cutting, as well as by increased grazing pressure from deer (Fuller et al. 1999). A study based on BBS results from 1995 to 2006 found a negative correlation between the abundance of deer and Nightingales at a regional level, with the species declining the most where deer population increase had been greatest, and modelling suggested that deer alone could have caused a decline of 14% in Nightingales over this period (Newson et al. 2012). Experimental approaches have demonstrated the effect of deer browsing on Nightingale numbers at site level: an exclusion experiment carried out over nine years found that Nightingale territory density within deer exclosures rose to ten times that of the rest of the wood, while radio-tracked Nightingales spent more time inside the deer exclosures than outside (Holt et al. 2010). Mist-netting confirmed that more Nightingales were present within the exclosures than in control plots, although the sample of birds was small (Holt et al. 2011). These findings fit with results across a wider range of breeding bird species that require low vegetation in woodland (Gill & Fuller 2007).

Woodland-scrub mosaics appear to be important breeding habitats for Nightingales, with implications for conservation practice (Holt et al. 2012c).

Information about conservation actions

The habitat requirements for Nightingale are well understood, and habitat management actions such as coppicing and control of deer numbers can be taken at a local level to promote the heterogeneous vegetation structure that Nightingales need. Woodland-scrub mosaics appear to be important breeding habitats for Nightingales (Holt et al. 2012c). A management advice sheet has been produced by the BTO and gives full details about the precise management requirements for Nightingales. Management plans should maximise the area of shrub at the vigorous thicket stage, typically involving rotational cutting on a 10-15 year cycle, preferably using reasonable sized blocks to create a coarse mosaic of larger patches instead of many small and widely dispersed patches of different ages (BTO 2015).

Although the habitat requirements are understood and can hence be applied locally, regional or national policies to encourage habitat management for Nightingales may be required to provide such habitat at a sufficiently wide scale and on an ongoing basis in order to enable the decline of this species to be stopped and reversed. Migrating Nightingales are attracted by singing males, hence one strategy as part of a wider landscape scale approach to conservation management for Nightingales would be to focus on providing this new habitat adjacent to existing sites.

Publications (4)

Extreme migratory connectivity and mirroring of non-breeding grounds conditions in a severely declining breeding population of an Afro-Palearctic migratory bird

Author: Kirkland, M., Annorbah, N.N.D., Barber, L., Black, J., Blackburn, J., Colley, M., Clewley, G., Cross, C., Drew, M., Fox, O.J.L., Gilson, V., Hahn, S., Holt, C., Hulme, M.F., Jarjou, J., Jatta, D., Jatta, E., Mensah-Pebi, E., Orsman, C., Sarr, N., Walsh, R., Zwartz, L., Fuller, R.J., Atkinson, P.W. & Hewson, C.M.

Published: 2025

BTO research uses tracking data to demonstrate that Nightingales breeding in the UK have an unusual degree of migratory connectivity to their non-breeding range in West Africa, with wider implications for both the UK conservation of this fast-declining species and for the conservation of migratory species in general.

29.01.25

Papers

Estimating national population sizes: Methodological challenges and applications illustrated in the common nightingale, a declining songbird in the UK

Author: Hewson, C.M., Miller, M., Johnston, A., Conway, G.J., Saunders, R., Marchant, J.H. & Fuller, R.J.

Published: 2018

Large-scale population estimates of species are used for several reasons, including the assessment and protection of important sites. However, determining a national population requires extensive surveying and using methods that allow counts to be scaled up to the number of birds actually present and across a larger area.

05.02.18

Papers

Flight Lines: Tracking the wonders of bird migration

Author: Mike Toms

Published: 2017

This stunning new book brings together the latest research findings, delivered through an accessible and engaging narrative by the BTO's Mike Toms, with the wonderful artwork generated through the BTO/SWLA Flight Lines project. If you have an interest in our summer migrants, then you'll welcome this fantastic opportunity to discover their stories through art and the written word.

21.08.17

Books and guides

Managing Scrub for Nightingales

Author:

Published: 2015

Habitat quality is a central concept in species conservation. Key resources must be available if a species is to breed successfully and maintain high survival. BTO work has identified critical elements of habitat for the Nightingale, a species celebrated for its remarkable song. This information has been summarised in a Conservation Advice Note – the first of its kind for the BTO.

29.04.15

Books and guides Conservation advice note