Nuthatch

Introduction

The Nuthatch is a charismatic inhabitant of woodland and an agile visitor to bird tables.

A handsome bird with a similar shape and structure to a woodpecker. The Nuthatch has a slate grey back, black eye stripe, white cheeks and orange breast; it is possible to distinguish male birds by their contrasting dark rufous flanks. Birds can be seen all year round in the UK, particularly in old deciduous woodland, although the species is absent from Northern Ireland and central to northern Scotland. The species possesses a range of loud whistling calls.

Nuthatches nest in tree holes or nest boxes, reinforcing the nest entrance with dried mud. Up to eight eggs are laid. The Nuthatch UK population trend shows a significant increase since the 1970s, which may be caused by a fall in the rate of nest failure and an increase in brood size and the number of chicks successfully reared per breeding attempt.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

Songs and Calls

Song:

Call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

Nuthatch abundance in the UK has increased rapidly since the mid 1970s. The increase has been accompanied by a range expansion into northern England and southern Scotland (Balmer et al. 2013). The BBS map of change in relative density between 1994-96 and 2007-09 indicates that, despite general increase over that period, there was evidence of some decrease in Kent, Cornwall and western Wales. There has been an increase across Europe since 1980 (PECBMS: PECBMS 2020a>).

Distribution

Nuthatches are widespread in winter and the breeding season throughout Wales, most of England and southern Scotland. They are absent from the Channel Islands, Isle of Man, Ireland and much of Scotland. Across England, they are notably absent from the Fens and the arable farmland of East Yorkshire.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

Both winter and breeding range of Nuthatches have expanded, for example by 38% in winter since the 1981–84 Winter Atlas. Range expansion, much of which has been in south Scotland, has also been accompanied by increases in relative abundance within the established range, particularly in western England and Wales.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

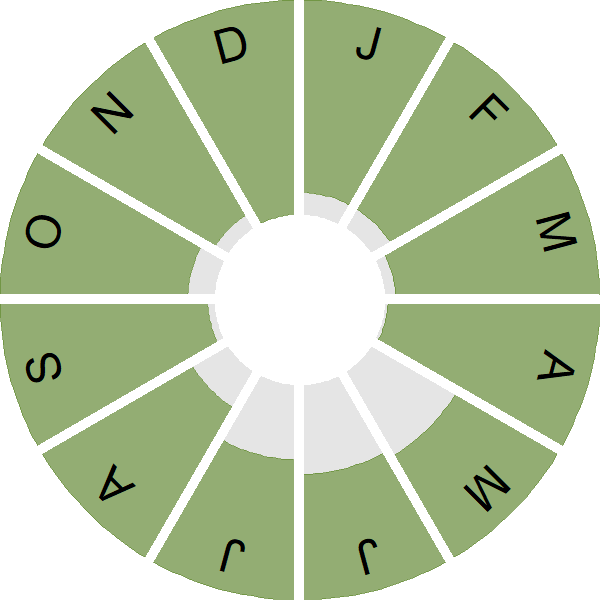

Seasonality

Nuthatch is recorded throughout the year, with detections peaking in late winter and early spring when the loud territorial song proclaims its presence.

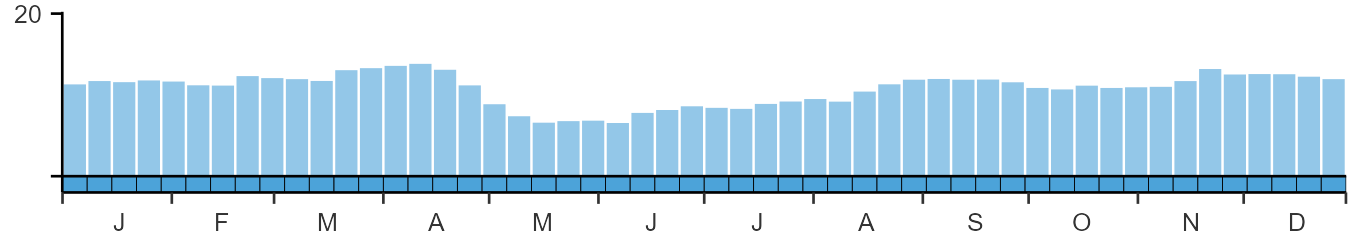

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

Habitats

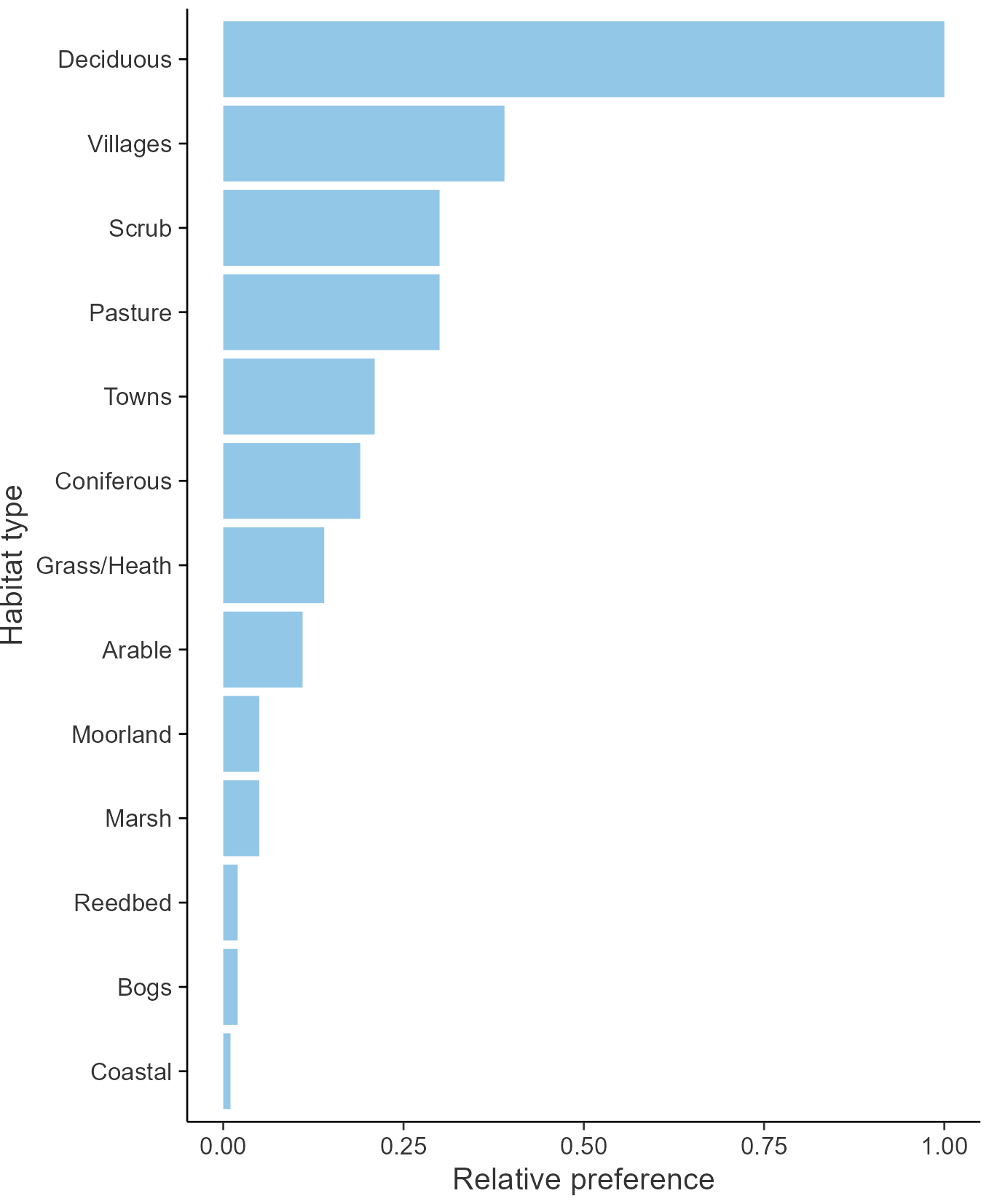

Breeding season habitats

Relative frequency by habitat

The graph shows the habitats occupied in the breeding season, with the most utilised habitats shown at the top. Bars of similar size indicate the species is equally likely to be recorded in those habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Incubation

Fledging

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

lifespan

Survival of adults

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Passeriformes

- Family: Sittidae

- Scientific name: Sitta europaea

- Authority: Linnaeus, 1758

- BTO 2-letter code: NH

- BTO 5-letter code: NUTHA

- Euring code number: 14790

Alternate species names

- Catalan: pica-soques blau

- Czech: brhlík lesní

- Danish: Spætmejse

- Dutch: Boomklever

- Estonian: puukoristaja

- Finnish: pähkinänakkeli

- French: Sittelle torchepot

- Gaelic: Sgoltan

- German: Kleiber

- Hungarian: csuszka

- Icelandic: Hnotigða

- Italian: Picchio muratore

- Latvian: dzilnitis

- Lithuanian: eurazinis bukutis

- Norwegian: Spettmeis

- Polish: kowalik (zwyczajny)

- Portuguese: trepadeira-azul

- Slovak: brhlík obycajný

- Slovenian: brglez

- Spanish: Trepador azul

- Swedish: nötväcka

- Welsh: Delor Cnau

- English folkname(s): Nutjobber, Woodcracker

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

The demographic causes of the population increase appear to be an increase in the number of fledglings per breeding attempt, larger brood sizes and a decrease in daily failure rates. However, it is unclear what the ecological drivers of these changes are.

Further information on causes of change

The number of fledglings per breeding attempt has increased strongly, through an increase in brood size and a fall in nest failure rates.

There is little evidence relating to Nuthatch population change in the UK. However, studies from Europe provide evidence that mild winters are likely to have helped this species. Kallander (1997) used a long-term data set (1977-91) to provide good evidence that Nuthatches in a Swedish national park had a population size in spring which co-varied positively with winter temperatures and suggest that increases in population size may be associated with increasing mean winter temperature. Nilsson (1982, 1987) also found that mortality was concentrated in winter and that starvation was probably the major cause. However, a long-term study in Poland from 1975 to 1990 found that bird numbers in spring were not significantly correlated with the severity of the preceding winter, though winter survival was higher in the unusually mild winter of 1989/90, which had a rich supply of hornbeam seeds (Wesolowski & Stawarczyk 1991). It is not possible to say whether such factors have also operated in the UK, as the climate here is considerably less extreme.

Several studies have also reported a link between population size and the size of food availability in the autumn. A study of two Nuthatch populations in Sweden provided good evidence that autumn population size was correlated with the size of the hazelnut crop, suggesting food supplies play a role, although beechmast crop was not correlated with overwinter survival and nor was autumn population size correlated with the population density in spring (Enoksson & Nilsson 1983, Enoksson 1990). In the studies by Nilsson mentioned above, the main density-dependent factor, recruitment of young of the year to the autumn population, was positively related to the current beechmast supply and negatively to the density of adults (Nilsson 1982, 1987). A long-term study in Poland from 1975 to 1990 also found that Nuthatch numbers seemed to be influenced by autumn seed supply and also availability of caterpillars in the preceding spring (Wesolowski & Stawarczyk 1991). Another continental study in Europe found that local survival in autumn was higher in beechmast years for juveniles, but not for adults and that local winter survival was not higher in years with than in years without beechmast (Matthysen 1989). Thus there is some evidence that increases in population size are linked to food supplies, but again, this has not been directly tested for UK birds.

Although there is no direct evidence available, Nuthatches are known to favour dead wood, and so it is possible that they may have benefited from the increase in dead wood in the UK (Amar et al. 2010a).

In Belgium, competition for nest sites with the non-native, invasive Ring-necked Parakeet was found to be detrimental to Nuthatches (Strubbe & Matthysen 2009). However, there is evidence showing that this is not a problem in the UK at present (Newson et al. 2011).

Information about conservation actions

The population of this species has increased consistently since the 1970s and it has expanded its range northwards, hence it is not a species of concern and no conservation actions are currently required.

Conservation actions benefiting other woodland species may also help Nuthatch. Habitat fragmentation may prevent Nuthatches from finding new sites (Verboom et al. 1991; Bellamy et al. 1998; van Langevelde 2008), and the provision of more frequent suitable patches of woodland across the landscape may therefore enable further colonisation and range expansion. Fragmentation may explain why numbers are relatively low and there are gaps in distribution in eastern England (Bellamy et al. 1998).

Publications (1)

A method to evaluate the combined effect of tree species composition and woodland structure on indicator birds

Author: Dondina, O., Orioli. V., Massimino, D., Pinoli, G. & Bani, L.

Published: 2015

Providing quantitative management guidelines is essential for an effective conservation of forest-dependent animal communities. Traditional forest practices at the stand scale simultaneously alter both physical and floristic features with a negative effect on ecosystem processes. Thus, we tested and proposed a method to define forestry prescriptions taking into account the combined effect of woodland structure and tree species composition on the presence of four bird indicator species (Marsh Tit Poecile palustris, European Nuthatch Sitta europaea, Short-toed Tree-creeper Certhya brachydactyla and Blue Tit Cyanistes caeruleus). The study was carried out in Lombardy (Northern Italy), from 2002 to 2005. By using a stratified cluster sampling design, we recorded Basal Area, one hundred tree trunk diameters at breast height (DBH) and tree species in 160 sampling plots, grouped in 23 sampling areas. In each plot we also performed a bird survey using the point count method. We analyzed data using Multimodel Inference and Model Averaging on Generalized Linear Mixed Models, with species presence/absence as the response variable, sampling area as a random factor and forest covariates as fixed factors. In order to test our method, we compared it with other two traditional approaches, which consider structural and tree floristic variables separately. Model comparison showed that our method performed better than traditional ones, in both the evaluation and validation processes. Based on our main results, in deciduous mixed forest where the exploitation demand is limited, we recommend maintaining at least 65 trees/ha with DBH>45cm. In particular, we advise keeping 70 trees/ha with DBH>50cm in chestnut forests and 300 trees/ha with DBH 20–30cm in oak forests. Conversely, in more exploited oak forests, we advise maintaining at least 670 trees/ha with DBH 15–30cm in chestnut forests and 100 trees/ha with DBH 10–15cm.

01.04.15

Papers