Pied Flycatcher

Introduction

The black and white male, sporting two white spots on the forehead, and the subtle brown and white female are scarce breeders in Britain and rare breeders in Ireland.

Wales's Oak woodlands are very much the breeding stronghold for this summer visitor but breeding populations can also be found in Scotland, and northern, central and south-west England. The Pied Flycatcher leaves its breeding territories in August and can be seen on migration during September and into October as it makes its way to its trans-Saharan winter quarters.

Pied Flycatchers begin arriving back during April and can be spotted at coastal migration watchpoints and they head back to their breeding locations. The UK population declined around the turn of the millennium, but this decrease has since levelled off.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

Songs and Calls

Song:

Call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

Pied Flycatchers are restricted to upland deciduous woods in parts of western and northern Britain. The proportions of CBC plots occupied rose during the 1980s, but the species was never numerous enough for trends to be estimated (Marchant et al. 1990). The 1988-91 breeding atlas revealed a small expansion in range from 1968-72, aided by the provision of nest boxes in new areas (Gibbons et al. 1993). BBS indicates that a decrease in abundance has occurred since 1995, prompting the species to be moved from the green to the amber list in 2009 and subsequently from amber to the UK red list at the latest review in 2015 (Eaton et al. 2015). This decrease occurred mainly in the late-1990s and early 2000s and the subsequent trend has been broadly stable. Nest-box occupancy rates have also fallen over a similar period at a number of sites monitored as RAS projects. There has been a across Europe since 1980 (PECBMS: PECBMS 2020a>).

Distribution

Breeding Pied Flycatchers are associated with the mature upland woodlands of western and northern Britain. They are widely distributed across most of Wales, parts of Shropshire and Herefordshire, and in northwest England from West Yorkshire through Cumbria to Northumberland, but are more patchily distributed in western Scotland.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

Marked range changes have occurred over the last 40 years or so. Pied Flycatcher breeding range expanded by 35% between 1968–72 and 1988–91 but there was a subsequent 27% range contraction from 1988–91 to 2008–11. Together these changes hint at a subtle westerly and northerly shift in distribution, with most of the recent losses involving thinning of the range along its eastern fringe and in southwest England. There has been a concurrent reduction in relative abundance almost everywhere since 1988–91.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

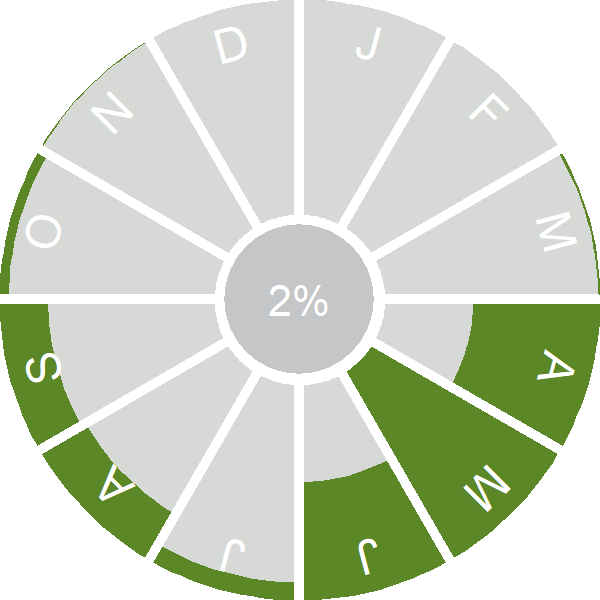

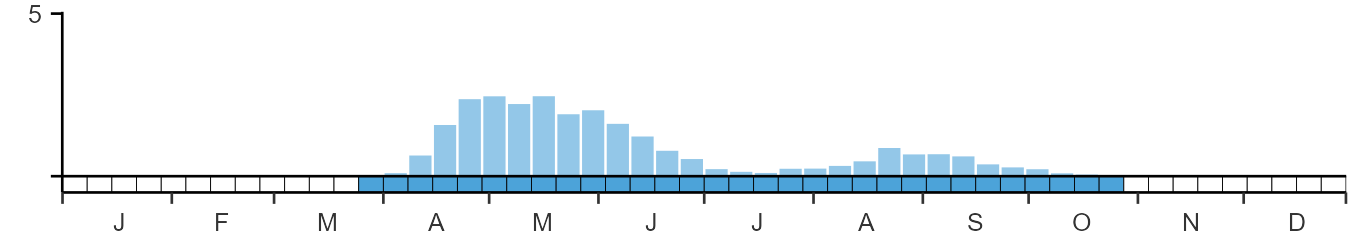

Seasonality

Pied Flycatcher is a localised summer migrant, arriving from mid April; autumn passage includes many continental birds and extents through August, September and early October.

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Incubation

Fledging

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

lifespan

Survival of adults

Survival of juveniles

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Passeriformes

- Family: Muscicapidae

- Scientific name: Ficedula hypoleuca

- Authority: Pallas, 1764

- BTO 2-letter code: PF

- BTO 5-letter code: PIEFL

- Euring code number: 13490

Alternate species names

- Catalan: mastegatatxes

- Czech: lejsek cernohlavý

- Danish: Broget Fluesnapper

- Dutch: Bonte Vliegenvanger

- Estonian: must-kärbsenäpp

- Finnish: kirjosieppo

- French: Gobemouche noir

- Gaelic: Breacan-glas

- German: Trauerschnäpper

- Hungarian: kormos légykapó

- Icelandic: Flekkugrípur

- Irish: Cuilire Alabhreac

- Italian: Balia nera

- Latvian: melnais muškerajs

- Lithuanian: margasparne musinuke

- Norwegian: Svarthvit fluesnapper

- Polish: mucholówka zalobna

- Portuguese: papa-moscas

- Slovak: muchárik ciernohlavý

- Slovenian: crnoglavi muhar

- Spanish: Papamoscas cerrojillo

- Swedish: svartvit flugsnappare

- Welsh: Gwybedog Brith

- English folkname(s): Coldfinch

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

The reasons for this decline are unknown, but there is good evidence that they lie at least partly outside the breeding season and are thought to be linked to changing conditions on wintering grounds and migration.

Further information on causes of change

The reasons for this decline are unknown, but there is good evidence that they lie at least partly outside the breeding season (Goodenough et al. 2009). No trends are evident in the number of fledglings per breeding attempt. Although the failure rate at the egg stage has shown a decrease, failure rate at the chick stage has increased. Clutch size increased until the mid-2000s but has since decreased slightly.

A study in the Netherlands found that a large proportion of Pied Flycatchers arrive later at the breeding grounds and do not breed in their first adult year (Both et al. 2017). Assuming that the same is true in the UK, this may complicate interpretation of trends and modelling to investigate the causes of change, particularly if the proportion of non-breeding first-year birds varies regionally and over time. Fatal interspecific competition for nest boxes is higher when Pied Flycatcher arrival coincides with peak laying in Great Tit, although late arriving male Pied Flycatchers were most likely to killed and therefore the deaths did not have any effect on the breeding population (Samplonius et al. 2019).

There is good evidence that declines are related to conditions outside the breeding season. Mallord et al. (2016) found no evidence that changes in woodland structure affected populations in six study areas in the west of the UK. Goodenough et al. (2009) found that decreasing breeding performance is contributing to decline, but that non-breeding factors are more important. Winter NAO index is a strong predictor of breeding population, probably because the North Atlantic oscillation influences food abundance in Africa and at migratory stopover points. Long-term autumn bird monitoring data from Russia were related to monthly mean temperatures on the West African wintering grounds; the positive relationship suggests that increasing bird numbers are explained by increasing mean November temperatures. Precipitation and European autumn, spring and breeding-range temperatures did not show a strong relationship (Chernetsov & Huettmann 2005). Thingstad et al. (2006) found that weather conditions at the flycatcher's wintering areas in western Africa were suspected to be responsible for the decrease in Scandinavia, although the breeding success of the sink populations was significantly correlated to June temperatures.

In the Netherlands, climate change may have brought about decline in Pied Flycatchers by advancing the peak period of food availability for this species in deciduous forests - the birds being unable to compensate for the change in food supply by breeding earlier (Both 2002, Both et al. 2006). A subsequent paper found that timing of spring migration has responded flexibly to climate change as recovery dates during spring migration in North Africa advanced by ten days between 1980 and 2002, which was explained by improving Sahel rainfall and a phenotypic effect of birth date. However, there was no advance in arrival dates on the breeding grounds, most likely due to environmental constraints during migration (Both 2010). Futhermore, declines were found to be stronger in forests, as these were more seasonal habitats whereas less seasonal marshes showed less steep declines (Both et al. 2009). Another more recent study in the Netherlands confirmed that arrival dates had not changed, but found that the timing of breeding and moult had both advanced, with earlier breeding increasing the time available for fledgling development and the probability that they will survive and join the breeding population (Tomotani et al. 2018). Climate change was also given as a potential factor by a Swedish study, that suggested warmer springs favoured resident Blue Tits and Great Tits over Pied Flycatchers, which were not able to adjust to increasing spring temperatures (Wittwer et al. 2015). Another study, looking at 10 European nest box schemes (including one in the UK) found that, although both tits and Pied Flycatchers had advanced their laying dates, tits had advanced more strongly by, on average, approximately one day per decade between 1991 and 2015 (Samplonius et al. 2018). It should be noted, however, that data presented here show that Pied Flycatchers in the UK have advanced their laying date by ten days since 1967, matching the change shown by Great Tit and exceeding the change of Blue Tit by two days.

Information about conservation actions

The reasons for the decline are unknown but it is likely that they lie at least partly outside the breeding season and hence it is uncertain whether conservation actions taken in the UK will have significant effects on the population trend.

However, Goodenough et al. (2009) suggested that, although less important than non-breeding factors, decreasing breeding performance may also be contributing to the decline, Therefore, breeding season conservation actions do remain useful for this species. Goodenough et al. (2009) recommend both the optimal placement of nestboxes (avoiding south-west facing boxes) and the management of woodland habitat to provide host plants for lepidotera larvae in order to increase food supplies. Elsewhere, a study in Finland found that birds preferred large (>5 ha) or medium sized (>1 ha) deciduous woodlands with the larger woods occupied first (Huhta et al. 2008); hence suitable sized patches of mature wood within the range of this species should be conserved where possible.

Publications (6)

Declines in invertebrates and birds – could they be linked by climate change?

Author: Pearce-Higgins, J.W. & Morris, R.K.A.

Published: 2023

The long-term declines evident in many bird and invertebrate species have their origins within a suite of potential drivers, one of which is climate change. As well as impacting bird species directly, could climate change be increasingly hitting bird populations through its impacts on their invertebrate prey?

09.01.23

Papers

Birds of Conservation Concern Wales 4: the population status of birds in Wales

Author: Johnstone, I.G., Hughes, J., Balmer, D.E., Brenchley, A., Facey, R.J., Lindley, P.J., Noble, D.G. & Taylor, R.C.

Published: 2022

The latest review of the conservation status of birds in Wales. The report assessed all 220 bird species which regularly occur in Wales. There are now 60 species of bird on the Red List, with 91 on the Amber List and just 69 - less than a third of the total number of species - on the Green List.

06.12.22

Reports Birds of Conservation Concern

Spatial consistency in drivers of population dynamics of a declining migratory bird

Author: Nater, C.R., Burgess, M.D., Coffey, P., Harris, B., Lander, F., Price, D., Reed, M. & Robinson, R.A.

Published:

While the study of a single population can provide important insights into what is driving population change at a local scale, we really need information from many different populations if we are to deliver effective conservation measures for declining migrant birds. This study helps to address this knowledge gap.

Papers

Tritrophic phenological match-mismatch in space and time

Author: Burgess M.D., Smith K.W., Evans K.L., Leech D., Pearce-Higgins J.W., Branston C.J., Briggs K., Clark J.R., du Feu C.R., Lewthwaite K., Nager R.G., Sheldon B.C., Smith J.A., Whytock R.C., Willis S.G., Phillimore A.B.

Published: 2018

The increasing temperatures associated with a changing climate may disrupt ecological systems, including by affecting the timing of key events. If events within different trophic levels are affected in different ways then this can lead to what is known as phenological mismatch. But what is the evidence for trophic mismatch, and are there spatial or temporal patterns within the UK that might point to mismatch as a driver of regional declines in key insect-eating birds?

23.04.18

Papers

Passerines may be sufficiently plastic to track temperature-mediated shifts in optimum lay date

Author: Phillimore, A.B., Leech, D.I., Pearce-Higgins, J.W. & Hadfield, J.D.

Published: 2016

19.05.16

Papers

Light-level geolocators reveal migratory connectivity in European populations of pied flycatchers Ficedula hypoleuca

Author: Ouwehand, J., Ahola. M.P., Ausems, A.N.M.A., Bridge, E.S., Burgess, M., Hahn, S., Hewson, C.M., Klaassen, R.H.G., Laaksonen, T., Lampe, H.M., W. Velmala, W. & C. Both, C.

Published: 2015

18.08.15

Papers