Red-throated Diver

Introduction

The Red-throated Diver has a restricted breeding distribution within Britain and Ireland, favouring small lochs and lakes close to the sea in the north of Ireland and north and west of Scotland.

The small breeding population is joined by a much larger number of birds during the winter months, when individuals can be found around our entire coastline – although with the greater proportion of these to be found off the east coast.

The Red-throated Diver is a well-studied, long-lived species; data from bird ringing reveal that individuals regularly reach 25 years of age. The species feeds mainly on small fish.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

ID Videos

This section features BTO training videos headlining this species, or featuring it as a potential confusion species.

Winter Divers

Songs and Calls

Song:

Flight call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

Breeding numbers are quite variable between years and not monitored annually by the BTO; trends are hard to assess except by intensive survey. There was a full UK survey in 1994 (935 pairs; Gibbons et al. 1997) and a repeat in 2006, by when the estimated UK breeding population had increased significantly by 34%, with stability in Shetland and Orkney but increase across the Hebrides and Scottish mainland (Dillon et al. 2009). Complete surveys of Shetland indicated a decrease of 36% there between 1983 and 1994 (Gomersall et al. 1984, Gibbons et al. 1997) and there was minor further decrease there by 2006 (Smith et al. 2009). The full surveys indicate that Shetland held 46% of the national total of breeding pairs in 1994 and 33% in 2006, though this decrease reflects the significant increases elsewhere in Scotland rather than the small decline in Shetland (Smith et al. 2009). JNCC's Seabird Monitoring Programme shows that breeding numbers at sample study areas in Shetland fluctuated without long-term change during 1980-2005, with low points in 1980, 2000 and 2004 (Mavor et al. 2008). Though previously amber listed through its 'depleted' status in Europe, the species was moved to the UK green list in 2015 (Eaton et al. 2015). Wintering numbers, mostly of birds from northern Europe, peaked in 2011/12 but have since decreased and are now similar to numbers in the early 1990s (WeBS: Frost et al. 2020).

Since the 1980s, there may have been some tendency for more pairs to hatch a second chick, although two-chick broods are only occasional in Orkney and changes in the distribution of nests recorded might have influenced the results. In 2011, however, there were fewer two-chick broods in Shetland than in any year since at least 1979 (Holling et al. 2013).

Distribution

Wintering Red-throated Divers are recorded all round the coast of Britain & Ireland, plus at a scatter of inland sites, mainly in northern and eastern England. The highest concentrations are along North Sea coasts, southwest Scotland and southwest Ireland. Breeding birds are restricted to freshwater lochs and bogs in Co. Donegal in Ireland and in north and west Scotland.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

Red-throated Diver winter range has expanded by 32% since the 1981–84 Winter Atlas, with a large part of this being off northwest Scotland and parts of western Ireland. Some of this increase may be due to better coverage but some gains are likely to be real.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

Seasonality

Red-throated Divers are recorded year-round

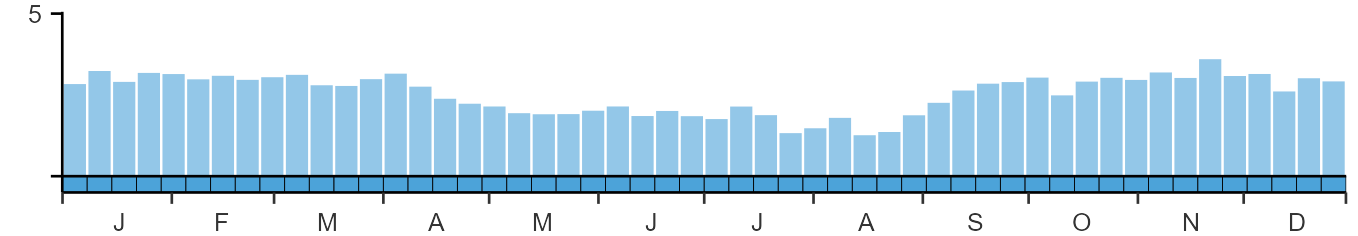

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Incubation

Fledging

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

lifespan

Survival of adults

Survival of juveniles

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Gaviiformes

- Family: Gaviidae

- Scientific name: Gavia stellata

- Authority: Pontoppidan, 1763

- BTO 2-letter code: RH

- BTO 5-letter code: RETDI

- Euring code number: 20

Alternate species names

- Catalan: calàbria petita

- Czech: potáplice malá

- Danish: Rødstrubet Lom

- Dutch: Roodkeelduiker

- Estonian: punakurk-kaur

- Finnish: kaakkuri

- French: Plongeon catmarin

- Gaelic: Learga-ruadh

- German: Sterntaucher

- Hungarian: északi búvár

- Icelandic: Lómur

- Irish: Lóma Rua

- Italian: Strolaga minore

- Latvian: brunkakla gargale

- Lithuanian: rudakaklis naras

- Norwegian: Smålom

- Polish: nur rdzawoszyi

- Portuguese: mobelha-pequena

- Slovak: potáplica malá

- Slovenian: rdecegrli slapnik

- Spanish: Colimbo chico

- Swedish: smålom

- Welsh: Trochydd Gyddfgoch

- English folkname(s): Rain Goose

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

There is little good evidence available regarding the drivers of the breeding population change in this species in the UK.

Further information on causes of change

No further information is available.

Information about conservation actions

The main drivers of change are not known for these species. However, because food for chicks is obtained largely from the sea close to breeding lochs, a reliable supply of suitable marine prey nearby is a requirement for successful breeding. Shortages of sand eels have recently been a major factor in depressing breeding success in Shetland (Forrester et al. 2007). Divers are thus vulnerable to losses of feeding grounds and to decreases in fish stocks and hence policies which protect marine areas adjacent to breeding areas would be prudent until the reasons for the decline have been confirmed.

Outside the breeding season, this species is believed to be among the most sensitive to offshore wind farms, and in particular at risk of displacement from wind farms (Furness et al. 2013; Wade et al. 2016; Heinanen et al. 2020), and therefore winter distribution should be taken into account when making decisions about wind farm developments, to protect both British and European breeding birds.

Publications (1)

Seabird foraging ranges as a preliminary tool for identifying candidate Marine Protected Areas

Author: Thaxter, C.B., Lascelles, B., Sugar, K., Cook, A.S.C.P., Roos, S., Bolton, M., Langston, R.H.W. & Burton, N.H.K.

Published: 2012

The UK government is committed to establishing an ecologically coherent network of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) to manage and conserve marine ecosystems. Seabirds are vital to such ecosystems, but until now these species have received little protection at sea. This is partly because there is scant information available on the oceanic regions they use at the different stages of their lifecycle. A new study led by the BTO, in partnership with the RSPB and Birdlife International, has sought to address this by bringing together work on how far UK-breeding seabirds travel from their colonies (typically in search of food for themselves or their chicks) during the breeding season.

01.01.12

Papers