Reed Bunting

Introduction

Not just a bird of reedbeds, this common species is widely distributed across much of Britain & Ireland throughout the year. It is absent only from the highest upland areas.

The male Reed Bunting has a striking black head with a white moustachial stripe; the female has a browner head, but the moustachial stripe is still visible. When perched, both sexes flirt their tail sideways, showing white outer feathers. The male's buzzing call is distinctive.

In winter, the Reed Bunting often joins other finches and buntings to feed in arable landscapes. At the end of the 20th century, BTO research attributed declines in these species to intensive agriculture reducing food availability over the winter months. This issue has been, to some extent, addressed through agri-environment schemes, and there has been a gradual overall increase in the UK population since the late-1990s. However, the picture is mixed with a significant decline in South-east England.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

ID Videos

This section features BTO training videos headlining this species, or featuring it as a potential confusion species.

Sparrows

Winter buntings

Songs and Calls

Song:

Call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

Reed Bunting abundance has fluctuated without a clear trend since the 1980s. The long-term WBS/WBBS trend shows a large decline and raises an alert, contrasting with the long-term CBC/BBS trend. However, the CBC/BBS trend shows a substantial increase in the first eight years until the mid-1970s followed by a substantial decline in the late 1970s and early 1980s, and therefore the trends would be consistent if they had both started in 1975. Results from BBS indicate significant population increase since 1995, though with a downturn from around 2008 to 2012. The BBS map of change in relative density between 1994-96 and 2007-09 indicates that increase over that period was widespread, but strongest in northeastern England, while decrease had occurred in Northern Ireland, Orkney and the far southeast. The initial decline placed Reed Bunting on the red list but in 2009, with evidence from BBS of some recovery in numbers, the species was moved from red to amber. There has been a decline across Europe since 1980 (PECBMS: PECBMS 2020a>).

Distribution

Breeding Reed Buntings are widely distributed across Britain and Ireland with gaps confined to the more barren uplands of northern Scotland, including Shetland and some Hebridean islands. Highest densities are associated mostly with large lowland vales and plains. Reed Buntings are mostly sedentary and distribution patterns in winter and the breeding season differ only where birds abandon upland areas in winter.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

The breeding distribution has been largely stable since the 1968–72 Breeding Atlas, despite a major population increase and subsequent decline in the 1970s. More recently, increases in abundance are apparent in eastern and northeast England and in southern Scotland, whilst declines are concentrated into southeast England. Some declines are also apparent in eastern Ireland.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

Seasonality

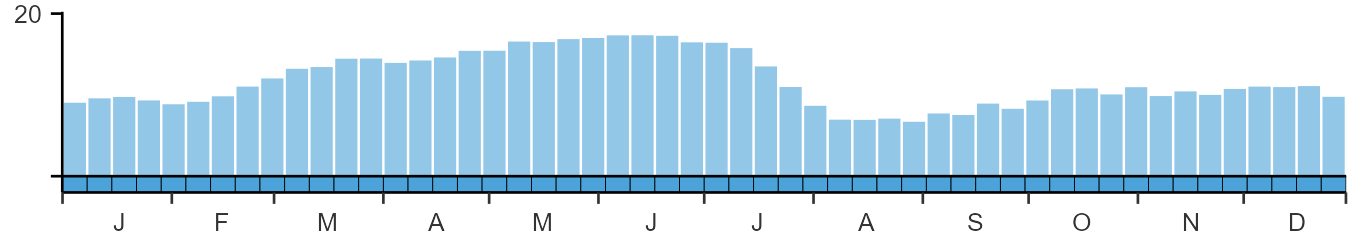

Reed Bunting is recorded throughout the year, with detections peaking at 20% of complete lists in summer when easily detected by song.

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

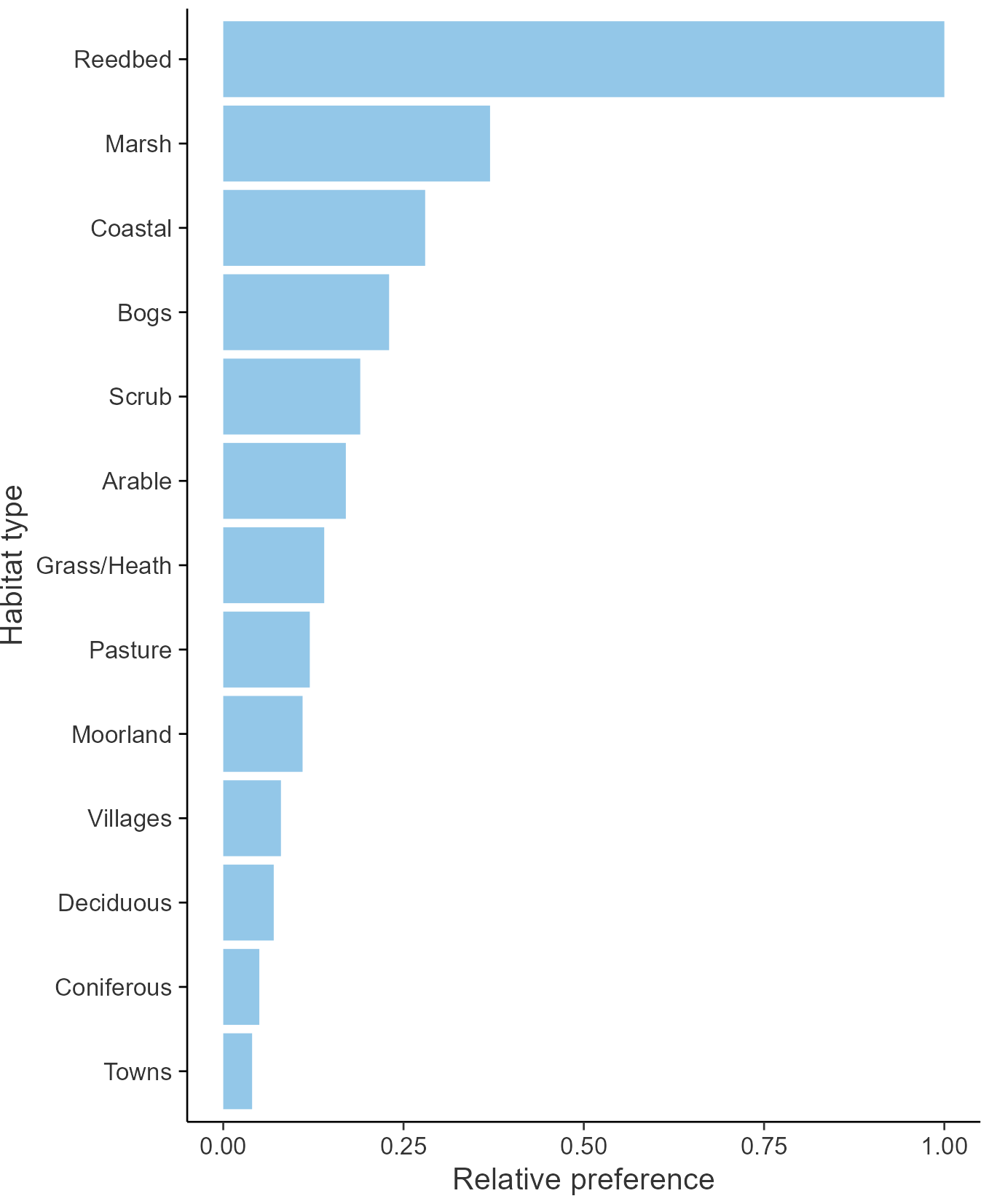

Habitats

Breeding season habitats

Relative frequency by habitat

The graph shows the habitats occupied in the breeding season, with the most utilised habitats shown at the top. Bars of similar size indicate the species is equally likely to be recorded in those habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Incubation

Fledging

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

lifespan

Survival of adults

Survival of juveniles

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Passeriformes

- Family: Emberizidae

- Scientific name: Emberiza schoeniclus

- Authority: Linnaeus, 1758

- BTO 2-letter code: RB

- BTO 5-letter code: REEBU

- Euring code number: 18770

Alternate species names

- Catalan: repicatalons

- Czech: strnad rákosní

- Danish: Rørspurv

- Dutch: Rietgors

- Estonian: rootsiitsitaja

- Finnish: pajusirkku

- French: Bruant des roseaux

- Gaelic: Gealag-dhubh-cheannach

- German: Rohrammer

- Hungarian: nádi sármány

- Icelandic: Seftittlingur

- Irish: Gealóg Ghiolcaí

- Italian: Migliarino di palude

- Latvian: niedru sterste, svilspraklitis

- Lithuanian: nendrine starta

- Norwegian: Sivspurv

- Polish: potrzos (zwyczajny)

- Portuguese: escrevedeira-dos-caniços

- Slovak: strnádka trstinová

- Slovenian: trstni strnad

- Spanish: Escribano palustre

- Swedish: sävsparv

- Welsh: Bras Cyrs

- English folkname(s): Reed/Fen Sparrow

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

Detailed demographic analyses suggest that the decline was driven by decreasing survival rates and that a subsequent population recovery may have been prevented by increased nest losses.

Further information on causes of change

The early increase in the CBC index was associated with a gradual spread into drier habitats, especially farmland, and it is likely that the subsequent decline was related to agricultural intensification. Detailed demographic analyses suggest that the decline was driven by decreasing survival rates and that a subsequent population recovery may have been prevented by increased nest losses (Peach et al. 1999). This is supported by a steep decline in CES productivity and by a major increase in failure rates at the egg stage, and a consequent fall in the number of fledglings per breeding attempt. Farmland densities are four times higher in oilseed rape than in cereals or setaside and this crop is crucial in reducing the dependency of the species on wetlands (Gruar et al. 2006).

Information about conservation actions

Like the related Yellowhammer, the research suggests that the main driver of the decline may have been reduced survival and therefore conservation actions to ensure sufficient food is available during winter will be needed to help reverse the decline. However, there is also evidence that increased nest losses may be preventing recovery and so this also needs to be addressed.

During winter, similar conservation actions to those proposed for Yellowhammer and other seed-eating birds are likely to also benefit the Reed Bunting. These include the direct provision of supplementary food, the retention of stubble fields, the planting of wild bird seed or game cover, reducing herbicide and pesticide use, and the provision of semi-natural habitats, e.g. through the provision of buffer strips, set-aside and conservation headlands, and through less intensive farmland management practices.

For Reed Buntings nesting in wetlands, a Swiss study suggested that, in order to reduce the probability of nest predation, wetland reserve management should aim to create larger wetlands and large dense reed patches rather than fragmented habitat (Pasinelli & Schlegg 2006). Away from wetlands, nesting densities in farmland are four times higher in oilseed rape than in cereals or set-aside and therefore this crop is crucial in reducing the dependency of the species on wetlands (Gruar et al. 2006).

Publications (1)

Birds of Conservation Concern Wales 4: the population status of birds in Wales

Author: Johnstone, I.G., Hughes, J., Balmer, D.E., Brenchley, A., Facey, R.J., Lindley, P.J., Noble, D.G. & Taylor, R.C.

Published: 2022

The latest review of the conservation status of birds in Wales. The report assessed all 220 bird species which regularly occur in Wales. There are now 60 species of bird on the Red List, with 91 on the Amber List and just 69 - less than a third of the total number of species - on the Green List.

06.12.22

Reports Birds of Conservation Concern