Ring-necked Parakeet

Introduction

With its bright green plumage and rose-coloured neck ring, It is difficult to think of a more incongruous British breeding bird than the Ring-necked Parakeet.

The Ring-necked Parakeet was accepted onto the British List in 1983. It has long been a popular cage-bird and the British breeding population, currently estimated at around 12,000 pairs, is the result of birds escaping from captivity over a long period of time. The birds breeding here in Britain constitute the most northerly breeding parrots in the world.

With a population centred on the south-east of England, this is a regular visitor to bird tables, feeding on a variety of seed, nuts, fruit and fat cakes. BTO Garden BirdWatch results show that it uses gardens throughout the year but peaks during November and December.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

Songs and Calls

Call:

Flight call:

Other:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

Following escapes and releases over many decades, this parrot, native to Africa and southern Asia, began breeding annually in the UK in 1969. Substantial but highly localised self-sustaining populations have since built up, with the two largest being in Greater London and in the Isle of Thanet, east Kent. Genetic modelling has traced the origin of these birds, brought here initially by the cagebird trade, to the northerly parts of the native range in Pakistan and northern India (Jackson et al. 2015).

Population modelling in the early 2000s revealed that populations in Greater London initially increased by approximately 30% per year, and those in Thanet by 15% per year, but that the range initially expanded by only 0.4 km per year in the Greater London area and hardly at all in Thanet (Butler 2003). National BBS data indicate more than a tenfold increase since 1995, and more substantial range expansion has occurred, particularly in Greater London (Balmer et al. 2013). There have been recent post-breeding estimates of more than 30,000 birds at large in the UK (Holling & RBBP 2011a). There are concerns about possible environmental and economic effects of the Ring-necked Parakeet population.

Distribution

The exotic introduced Ring-necked Parakeet has had a long association with Greater London and parts of eastern Kent, but the species has now colonised several large conurbations, including Liverpool, Manchester, Sheffield and Birmingham, and non-breeding birds were reported from several squares in southern Scotland during the 2007–11 atlas. The next atlas is likely to show further gains.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

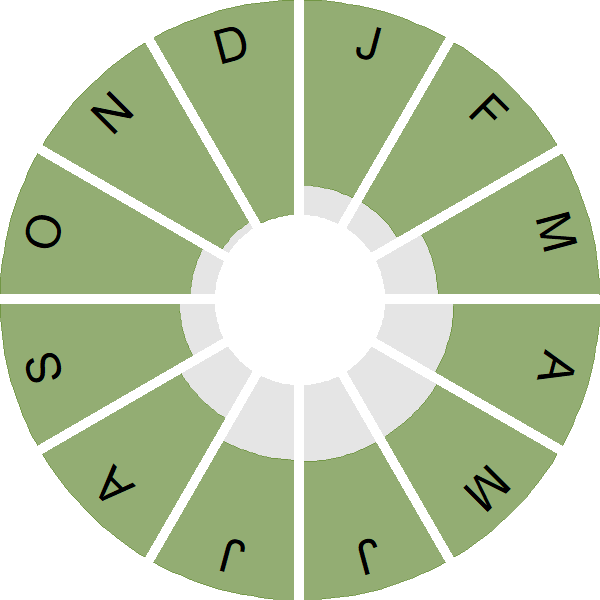

Seasonality

Ring-necked Parakeets are recorded consistently throughout the year in colonised areas.

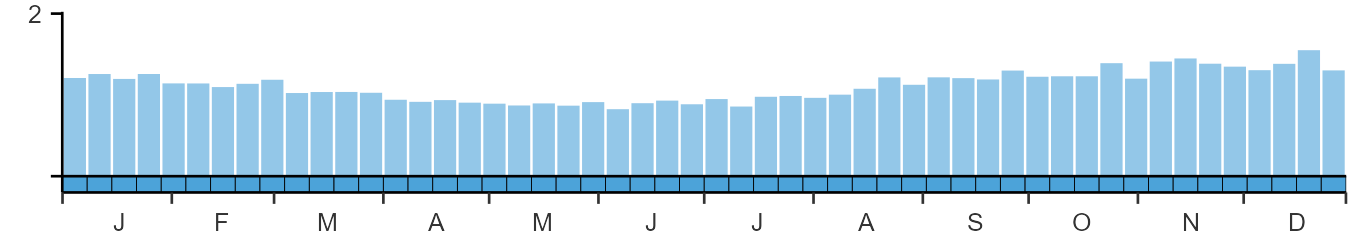

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

lifespan

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Psittaciformes

- Family: Psittaculidae

- Scientific name: Psittacula krameri

- Authority: Scopoli, 1769

- BTO 2-letter code: RI

- BTO 5-letter code: RINPA

- Euring code number: 7120

Alternate species names

- Catalan: cotorra de Kramer

- Czech: alexandr malý

- Danish: Alexanderparakit

- Dutch: Halsbandparkiet

- Estonian: kaeluspapagoi

- Finnish: kauluskaija

- French: Perruche à collier

- German: Halsbandsittich

- Hungarian: örvös papagáj

- Icelandic: Grænpáfi

- Italian: Parrocchetto dal collare

- Latvian: Kramera papagailis

- Lithuanian: Kramerio žieduotoji papuga

- Norwegian: Halsbåndparakitt

- Polish: aleksandretta obrozna

- Portuguese: periquito-rabijunco

- Slovak: alexander malý

- Slovenian: aleksander

- Spanish: Cotorra de Kramer

- Swedish: halsbandsparakit

- Welsh: Paracît torchog

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

Levels of breeding productivity are sufficient to account for the observed population increases, assuming mortality remains low.

Further information on causes of change

From 108 nests located during 2001-03, the mean first-egg date was 26 March, median clutch size was 4, and overall nest success 72%, making productivity sufficient to account for the observed population rise, assuming mortality rates remained low (Butler et al. 2013).

The species has already been reported causing economic damage to crops, as has occurred elsewhere in its native and introduced range (Butler 2003). A recent study in Belgium has identified negative effects on breeding Nuthatch, but not on other native hole-nesting species, such as Starling (Strubbe & Matthysen 2007, 2009, Strubbe et al. 2010). No such effects have yet been detected in Britain, however (Newson et al. 2011). A Spanish study reported that the species had caused the decline of Noctule Bats in a Seville park, with parakeets observed attacking bats to gain access to nest holes (Hernandez-Brito et al. 2018). There is also evidence that the presence of parakeets reduces feeding rates among native birds (Peck et al. 2014), with a study using video recording in Paris suggesting that Starling was most impacted (Le Louarn et al. 2016).

Information about conservation actions

As a non-native introduced breeding species, this species does not have a conservation status in the UK and hence is not a species of conservation concern.

On the contrary, there are concerns about the potential future impact of increasing parakeet numbers on other species, which could mean that conservation action to control parakeets could possibly be required in the future in order to protect native species (see Causes of Change section, above).

Publications (1)

Not in the countryside please! Investigating UK residents’ perceptions of an introduced species, the ring-necked parakeet (Psittacula krameri)

Author: Pirzio-Biroli, A., Crowley, S.L., Siriwardena, G.M., Plummer, K.E., Schroeder, J. & White, R.L.

Published: 2024

The Ring-necked Parakeet is a non-native species in Europe, with more than 90 established breeding populations across the continent, particularly in urban areas. The UK, and Greater London especially, is home to the largest of these non-native European populations. This study used an online survey to examine people’s perception of this species across the UK, and found that negative views of Ring-necked Parakeets are stronger in rural areas than in towns and cities.

02.05.24

Papers