Sparrowhawk

Introduction

This fierce bird of prey is a woodland species, but will come into close contact with people when it visits garden bird feeders for an easy meal.

Sparrowhawks are widespread across Britain and Ireland, with a population that has completely recovered from a deep decline caused by the use of organochlorine pesticides in the 1950s and 1960s.

Sparrowhawks avoid northern Scottish uplands and offshore islands. Elsewhere they are a common sight, even over towns, where their flapping flight interspersed with glides and classic raptor silhouette can be seen by eyes alert to the skies. Across lowland England Sparrowhawks prefer varied woodland landscapes and use hedges as cover for their dashing strikes to secure their small bird prey.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

Songs and Calls

Call:

Alarm call:

Young call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

Between the 1970s and the mid 1990s, the CBC charted a steep increase in this species. Many former haunts especially in the Midlands and east of England were reoccupied between the first two atlas periods (Gibbons et al. 1993). The population stabilised from the mid 1990s, though BBS figures suggest a moderate decline has occurred in England over the last ten years. Nest productivity has risen, especially during the period of strong population increase, although it has subsequently fallen during the period of decline. Numbers have been broadly stable across Europe since 1980 (PECBMS: PECBMS 2020a>).

Distribution

Sparrowhawks are widespread across most of Britain & Ireland, with the exception of the northern Scottish uplands and some island groups. Abundance is highest in lowland areas such as eastern England, and particularly low in northwest Scotland and other upland areas.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

Sparrowhawk range has expanded in Britain through the series of breeding atlases as populations recovered from the low point in the early 1960s caused by the widespread agricultural use of organochlorine pesticides.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

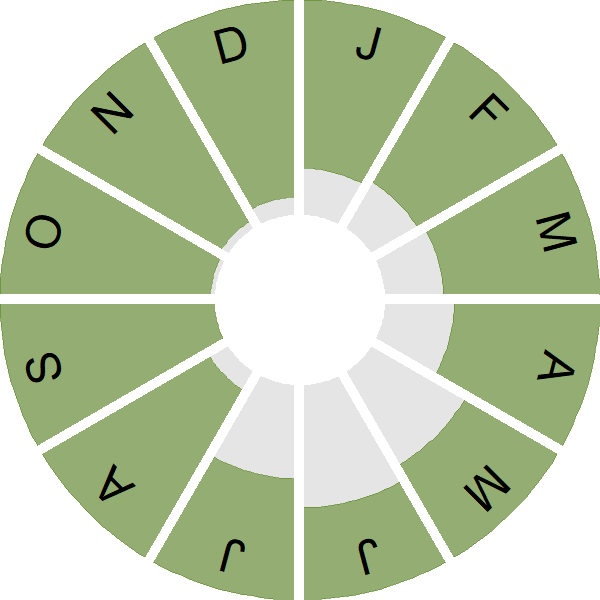

Seasonality

Sparrowhawks are present year-round.

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

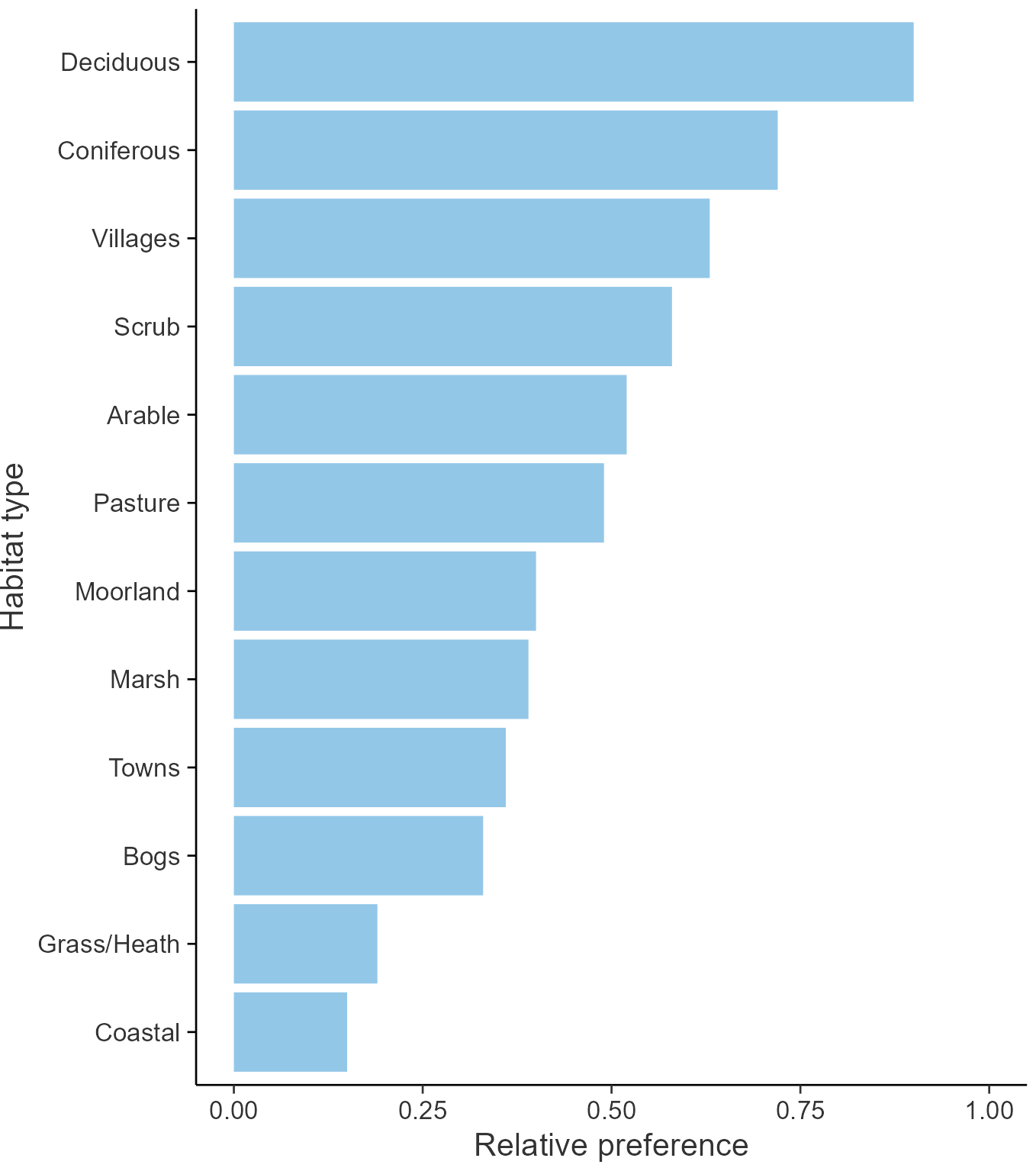

Habitats

Breeding season habitats

Relative frequency by habitat

The graph shows the habitats occupied in the breeding season, with the most utilised habitats shown at the top. Bars of similar size indicate the species is equally likely to be recorded in those habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Incubation

Fledging

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

lifespan

Survival of adults

Survival of juveniles

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Accipitriformes

- Family: Accipitridae

- Scientific name: Accipiter nisus

- Authority: Linnaeus, 1758

- BTO 2-letter code: SH

- BTO 5-letter code: SPARR

- Euring code number: 2690

Alternate species names

- Catalan: esparver comú

- Czech: krahujec obecný

- Danish: Spurvehøg

- Dutch: Sperwer

- Estonian: raudkull

- Finnish: varpushaukka

- French: Épervier d’Europe

- Gaelic: Speireag

- German: Sperber

- Hungarian: karvaly

- Icelandic: Sparrhaukur

- Irish: Spioróg

- Italian: Sparviere

- Latvian: zvirbulvanags, veja vanags

- Lithuanian: paprastasis paukštvanagis

- Norwegian: Spurvehauk

- Polish: krogulec (zwyczajny)

- Portuguese: gavião-da-europa

- Slovak: jastrab krahulec

- Slovenian: skobec

- Spanish: Gavilán común

- Swedish: sparvhök

- Welsh: Gwalch Glas

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

There is good evidence that improved breeding success due to a decline in organochlorine pesticide use is the most likely cause of the increase in this species, but that reduced survival, especially of young birds, may be driving the decline in Scottish populations.

Further information on causes of change

Sparrowhawks suffered a severe population crash caused by organochlorine pesticides in the 1950s and 1960s, when the species was extinguished from large areas of lowland Britain (Newton 1986, 2013). Studies of this species in eastern England confirmed this, and the recovery of the Sparrowhawk in this area was primarily dependent on declining organochlorine contamination which resulted in an improvement of breeding success mainly due to an increase in hatching success, itself associated with improved eggshell thickness and reduced egg breakage (Newton & Wyllie 1992). The figures above support this, showing improving numbers of fledglings per breeding attempt, a fall in failure rates at the egg stage and increases in brood size. Integrated population modelling supports the importance of productivity, as well as the survival of first-year birds, in determining population change (Robinson et al. 2014). This also suggested that an unknown factor, perhaps the availability of good-quality territories (and hence the number of individuals that can breed each year), also influences the annual population change.

Comparison of an increasing population in east-central England with stable and decreasing populations in southern Scotland showed that differences in population trend were associated mainly with differences in the recruitment of new breeders (greatest in the increasing and lowest in the decreasing population) and in age of first breeding (earliest in the increasing and latest in the decreasing population). There were also differences in the annual survival of breeders (greater in the increasing population) while differences in breeding success between areas were slight and non-significant (Wyllie & Newton 1991). A comprehensive long-running study of Sparrowhawks in Scotland during 1972-86 provides further detailed evidence. Overwinter loss operating in the period between the fledging of young and subsequent recruitment to the breeding population was identified as the key factor, explaining 77% of the variance in total annual loss, and largely accounting for the pattern of change in breeding numbers (Newton 1988). Work by Newton & Marquiss (1986) found that annual survival of established breeders and breeding performance was the same in both a declining and increasing population, but that recruitment of incoming breeders was lower in the declining population and state that this was the main proximate cause of decline. A more recent study in Scotland during 2009-12 found that nest failure rates were significantly higher in rural populations than in urban areas, with further work required to understand the causes behind this difference (Thornton et al. 2017).

The population has stabilised since the mid 1990s and, possibly through the effects of intraspecific competition, average brood size has begun to fall again (see above) and a recent moderate decline in abundance has occurred. Trichomonosis, the disease which has caused the recent very steep decline of Greenfinch, has also been recorded in Sparrowhawks (Chi et al. 2013); however evidence of any link between the disease and the recent Sparrowhawk decline is yet to be shown.

Information about conservation actions

The drivers behind the recent declines of this species are unclear and further research is needed to understand the causes. If specific reasons can be identified to explain why recruitment is lower in some populations and why nest failure rates are higher in rural populations, then appropriate targeted conservation actions can be proposed.

Similarly, raptors are known to suffer from trichomonosis, so if there is evidence that this is contributing to the decline it would be useful to confirm this. If so, there are currently no obvious conservation actions that can be taken apart from promoting improved hygiene at feeding stations, assuming that the disease is passed to sparrowhawks when they feed on infected birds.

Anticoagulant rodenticides (rat poisons) were found in 39 out of 42 UK Sparrowhawk carcasses examined between 2010 and 2012, in most cases at low concentrations; two birds had slighter higher levels, although with no clear evidence that rodenticides were a contributory cause of death (Walker et al. 2014). Nevertheless, precautions such as prompt removal and safe disposal of poisoned rates, as well as continued monitoring, would be prudent.