Whitethroat

Introduction

A summer visitor from Africa, this small, brown warbler frequents hedgerow and scrubby areas across Britain & Ireland from April to October.

Its winter quarters in Africa occupy the dry Sahel just to the south of the Sahara. This area is subject to prolonged periods of drought which affect Whitethroat overwinter survival. Such conditions led to a crash of 90% in UK Whitethroat numbers in the late-1960s, from which this species is still recovering.

Whitethroats breed throughout the UK and it can be found from Cornwall to northern Scotland, as well as across Ireland. The species is only absent from our mountain tops.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

ID Videos

This section features BTO training videos headlining this species, or featuring it as a potential confusion species.

Warbler Identification Workshop Part 4: The Whitethroats

Songs and Calls

Song:

Call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

Whitethroat numbers had been stable for a few years up to 1968 but, despite a normal departure for their West African wintering grounds in autumn 1968, crashed by around 70% between the 1968 and 1969 breeding seasons (Winstanley et al. 1974). They fluctuated around their lower level until the mid 1980s, since when the population has sustained a consistent shallow recovery. Recovery of the UK population has been most apparent along linear waterways. The BBS map of change in relative density between 1994-96 and 2007-09 indicates that increase over that period was strong in Scotland and parts of northern and southern England, contrasting with a decrease in parts of East Anglia. More recent BBS data show that, since 1995, a rapid increase has occurred in Scotland and a shallow increase in England, but this contrasts with a moderate decline in Wales over the same period. There has been an increase across Europe since 1980 (PECBMS: PECBMS 2020a>). After a spell on the UK amber list during 2009-15, warranted by the limited extent of its UK recovery, further population increase has returned Whitethroat to the green list at the latest review (Eaton et al. 2015).

Distribution

Whitethroats are distributed throughout Britain and Ireland with the exception of higher uplands, particularly of northern England and Scotland. They are scarce in the Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isles and southwest Ireland. Densities are low in Ireland, highest in the lowlands of southern, central and eastern England.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

Whitethroat numbers have changed considerably, linked with changing rainfall patterns in their African wintering grounds. Corresponding changes in range size are less apparent, although there has been an increase in density between c.1990 and c.2010.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

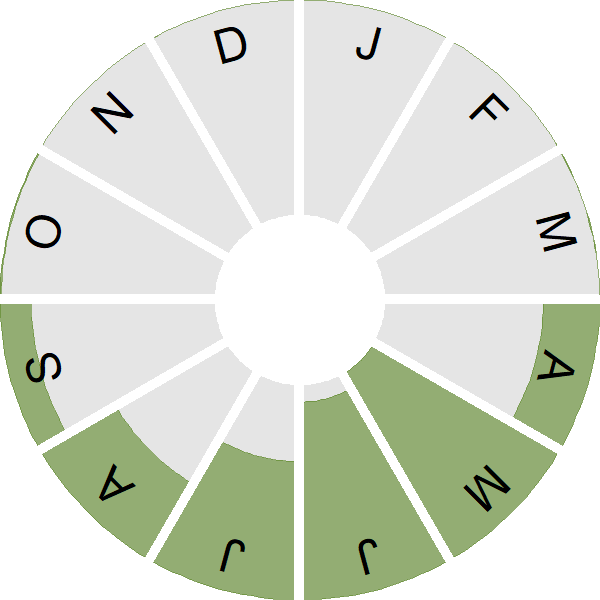

Seasonality

Whitethroat is a summer visitor, arriving in mid April with most birds departed by the end of September.

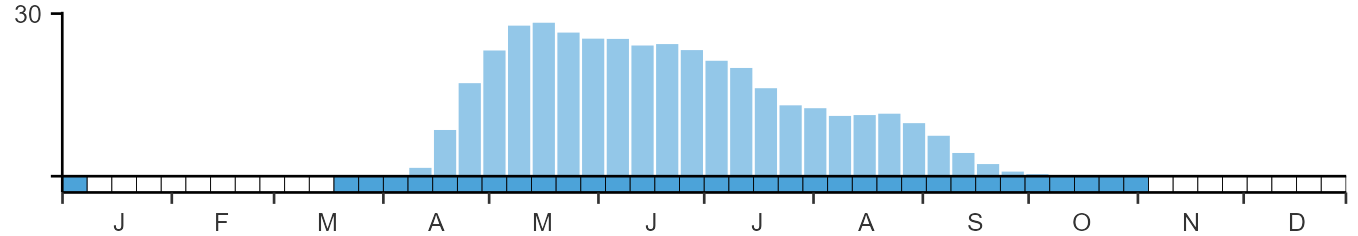

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

Habitats

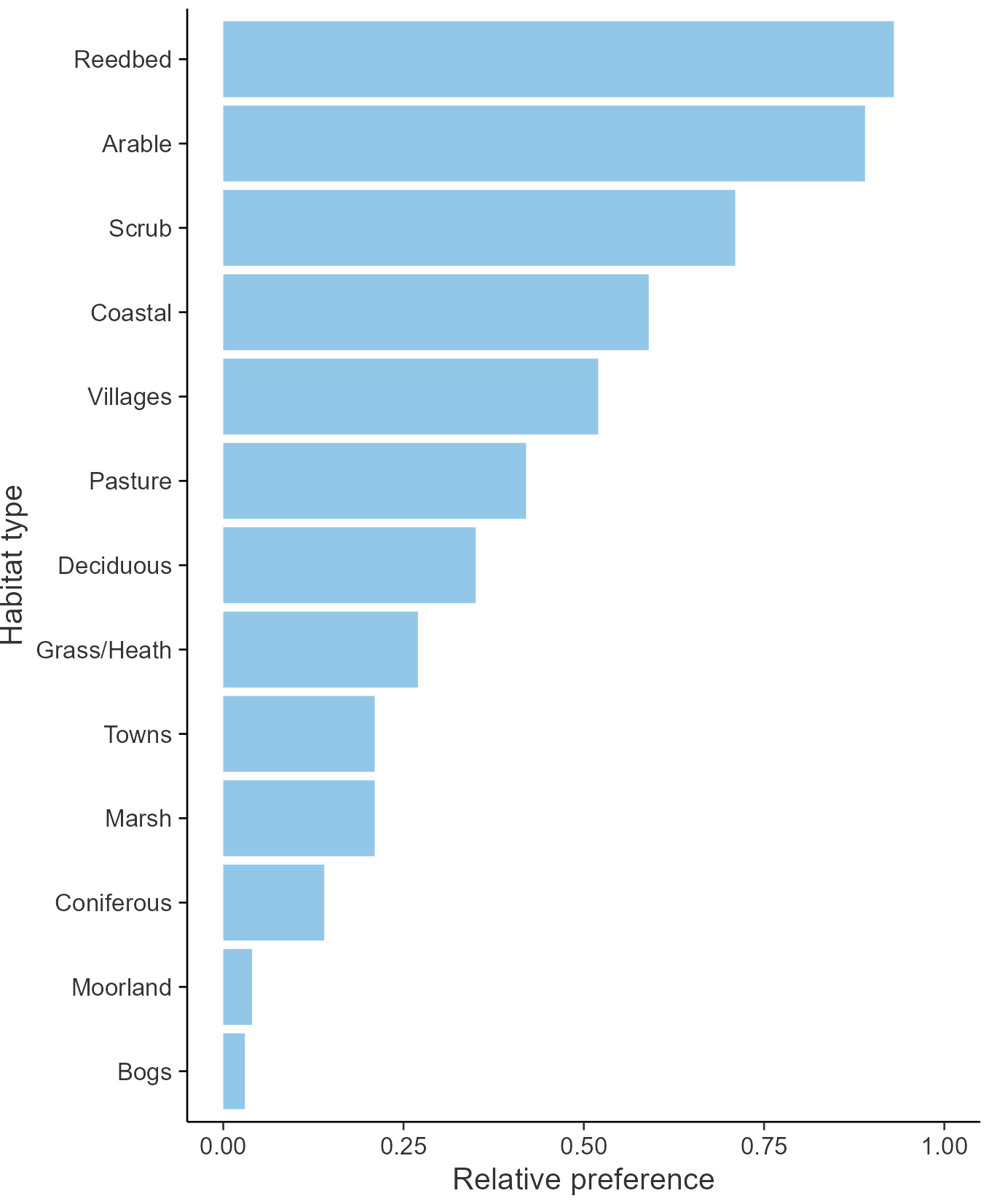

Breeding season habitats

Relative frequency by habitat

The graph shows the habitats occupied in the breeding season, with the most utilised habitats shown at the top. Bars of similar size indicate the species is equally likely to be recorded in those habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Incubation

Fledging

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

lifespan

Survival of adults

Survival of juveniles

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Passeriformes

- Family: Sylviidae

- Scientific name: Curruca communis

- Authority: Latham, 1787

- BTO 2-letter code: WH

- BTO 5-letter code: WHITE

- Euring code number: 12750

Alternate species names

- Catalan: tallareta comuna

- Czech: penice hnedokrídlá

- Danish: Tornsanger

- Dutch: Grasmus

- Estonian: pruunselg-põõsalind

- Finnish: pensaskerttu

- French: Fauvette grisette

- Gaelic: Gealan-coille

- German: Dorngrasmücke

- Hungarian: mezei poszáta

- Icelandic: Þyrnisöngvari

- Irish: Gilphíb

- Italian: Sterpazzola

- Latvian: brunsparnu kaukis

- Lithuanian: rudoji devynbalse

- Norwegian: Tornsanger

- Polish: cierniówka

- Portuguese: papa-amoras

- Slovak: penica obycajná

- Slovenian: rjava penica

- Spanish: Curruca zarcera

- Swedish: törnsångare

- Welsh: Llwydfron

- English folkname(s): Nettlecreeper

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

There is good evidence that the major changes in the population of this species have been driven by conditions on its wintering grounds and so are related to overwinter survival.

Further information on causes of change

In a pioneering study, Winstanley et al. (1974) provided good evidence to link the 1969 crash to drought in the Whitethroat's wintering grounds in the western Sahel, just south of the Sahara Desert. More recent analysis of data from four western European countries found a strong relationship between overwinter survival and population change over a 20-year period (Johnston et al. 2016). Correspondingly, Baillie & Peach (1992) found that breeding performance was poorly correlated with population changes. They found that fluctuations in losses of adult birds were correlated with conditions on the wintering grounds, and were correlated with Sahel rainfall. Thus, the population appears to be limited by food resources on the wintering grounds, because rainfall in the dry Sahelian landscape promotes greater invertebrate abundance. There has been no long-term trend in the number of fledglings per breeding attempt (see above). Productivity, as measured by CES, rose during the 1980s and has since fluctuated and fallen back.

More recent work has provided good evidence that the density of Whitethroats wintering in the Sahel is correlated with the number and size of trees, and that the increase in overall density of trees was related to an increase in Whitethroats in the area (Stevens et al. 2010). Wilson & Cresswell (2006) found that Whitethroats were most common in areas with intermediate tree heights. They suggest that Whitethroats appear to be able to survive in extremely degraded habitats, yet may be vulnerable to the disappearance of Salvadora trees, the fruit of which assists pre-migratory fattening. This is likely to be a separate mechanism to the earlier rainfall mechanism contributing to the population decline and is probably linked to the more recent gradual increase.

Information about conservation actions

The 1969 crash was caused by problems in the wintering area and research suggests that recent changes may also be linked to the availability of food resources in winter (see Causes of Change section, above). It is unclear, therefore, how much impact conservation actions during the breeding season will have on the population trends, if any. However, ensuring that good quality breeding habitat is available will help to ensure that breeding productivity remains high and that numbers have the potential to increase during good wintering years.

A study in Leicestershire found that providing low hedges and uncut 2 m buffer strips of perennial herbaceous vegetation alongside these hedges would benefit Whitethroats on farmland (Stoate & Szczur 2001). A Polish study looking at linear habitats found that Whitethroat preferred habitat with structural heterogeneity and was attracted by brambles and nettles (Szymanski & Antczak 2013). As well as management of hedges and adjacent vegetation, other actions to provide suitable areas of mixed scrub may also benefit Whitethroat, including long-term set-aside and provision of exclosures to prevent deer browsing and exclude livestock.

Publications (1)

Breeding periods of hedgerow-nesting birds in England

Author: Hanmer, H.J. & Leech, D.I.

Published: Spring 2024

Hedgerows form an important semi-natural habitat for birds and other wildlife in English farmland landscapes, in addition to providing other benefits to farming. Hedgerows are currently maintained through annual or multi-annual cutting cycles, the timing of which could have consequences for hedgerow-breeding birds.The aim of this report is to assess the impacts on nesting birds should the duration of the management period be changed, by quantifying the length of the current breeding season for 15 species of songbird likely to nest in farmland hedges. These species are Blackbird, Blackcap, Bullfinch, Chaffinch, Dunnock, Garden Warbler, Goldfinch, Greenfinch, Linnet, Long-tailed Tit, Robin, Song Thrush, Whitethroat, Wren and Yellowhammer.

05.03.24

Reports Research reports