Small outbreaks of avian influenza in wild birds are relatively common. They are usually restricted to waterbirds like ducks, geese and swans, occur over the winter months and die down as spring approaches.

However, an outbreak beginning in 2021 is still circulating in wild bird populations and has had huge impacts on both breeding and wintering species.

The outbreak in 2021

Key species

- Great Skua

- Barnacle Goose

Locations

- Hirta, Flannan Isles, Orkney, Shetland and Fair Isles

- Solway Firth

The ongoing outbreak of avian influenza was first observed in the 2021 breeding season. Mass mortality events occurred in Great Skua colonies on several Scottish islands, and when scientists tested the dead birds for disease, they found that the highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza strain (HPAI) was present.

In the winter of 2021, scientists confirmed that HPAI was also present in Barnacle Geese wintering on the Solway Firth.

The outbreak in 2022

Key species

- Great Skua

- Gannet

- Other breeding seabirds

Locations

- Widespread, but particularly in coastal colonies in Scotland

Unusually, the outbreak did not die down in spring 2022, as expected. Instead, it spread to other bird species and across much of the UK, persisting throughout the summer.

The virus moved into breeding seabird colonies around the UK’s coast for what is believed to be the first time, and sadly, many thousands of birds died. Great Skua and Gannet colonies were particularly badly affected.

Monitoring work carried out by the Animal and Plant Health Agency (APHA) confirmed HPAI in other species including raptors, waders, and gamebirds. The virus was also widely reported across continental Europe.

The outbreak in 2023

Key species

- Black-headed Gull

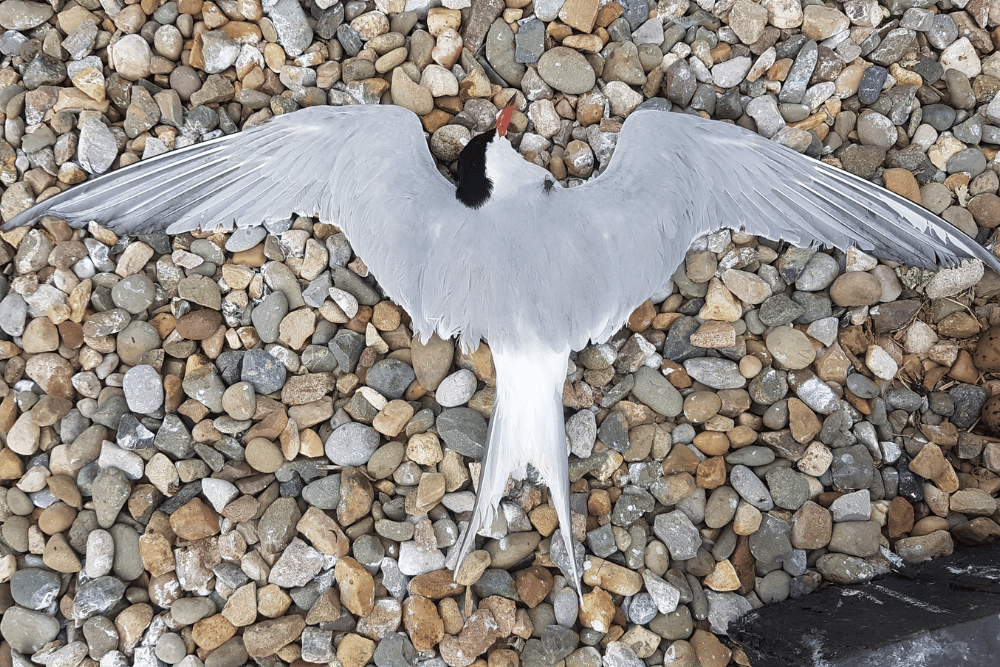

- Common Tern

- Kittiwake

- Guillemot

Locations

- Widespread, from the south coast, the midlands and East Anglia north to Aberdeenshire

The outbreak continued into 2023, infecting a different suite of species across a different geographical distribution.

In January, avian influenza was still affecting wildfowl species such Pink-footed and Greylag Goose, but cases appeared to be falling.

In March, however, mortality in breeding Black-headed Gull colonies in the Midlands began to rise, and testing confirmed the presence of avian influenza. Black-headed Gulls spend the winter months in continental Europe and it is thought that they carried the virus back to the UK on their return migration.

The virus then spread from Black-headed Gull colonies to Common Terns, which return to the UK later in spring and nest in colonies that are often adjacent to those of Black-headed Gulls.

Reports of sick and dead Black-headed Gulls and Common Terns allowed researchers to track the spread of the virus from the Midlands to Wales, East Anglia and the south coast, then north through upland reservoir sites before leaping to south-west Scotland and Northern Ireland. The virus continued to infect many gull and tern species, but was not reported in most other seabirds in significant numbers.

In summer, however, reports of dead birds washing up on beaches on the east coast of Scotland revealed that the outbreak had spread to seabirds for the second breeding season in a row.

Because this outbreak occurred some distance from other avian influenza reports, the transmission route for the infection (how the virus spread to these birds in Scotland) is poorly understood. The virus may have been passed from continental-breeding Kittiwakes to UK-breeding Kittiwakes while both populations foraged together in the North Sea.

From north-east Scotland, the virus spread rapidly down the east coast to north Norfolk, where it infected many tern colonies and again caused high levels of mortality.

During the breeding season, auks were also affected, mostly Guillemots, and there was significant Guillemot mortality in Pembrokeshire in July.

In the autumn of 2023, very few cases of HPAI-related deaths were reported.

Why is winter a time of particular concern?

Many bird species migrate away from their breeding grounds in autumn, to spend the winter months in warmer regions. The potential for migratory birds to spread the disease across continents was highlighted by evidence from North America, which suggested that migrating geese probably carried the disease across the Atlantic.

- Britain and Ireland are part of a wider flyway that links populations from many different breeding areas, meaning there are many potential transmission routes for disease.

Britain and Ireland host internationally important wintering waterfowl populations which are known to be susceptible to avian influenza and have already suffered high mortality from the disease. Scientists are concerned that the winter months could bring more cases of avian influenza into these already vulnerable populations.

The impact of avian influenza on bird populations

The full impact of the current avian influenza outbreak is yet to be formally quantified, but reports so far suggest that 135 bird species in the UK have been affected by the disease. This includes seabirds, waterbirds, waders, raptors, corvids, and small perching birds (passerines) like finches, warblers and thrushes.

The wide range of birds infected by the virus suggests that it is present in low levels across the wider countryside in what is known as a ‘reservoir’; this means the virus has the potential to spread quickly through more vulnerable species if they are exposed to it.

Ducks, geese and swans

Waterbirds are particularly vulnerable to avian influenza, and many species have been impacted since the outbreak began in 2021.

Waterbirds are particularly vulnerable to avian influenza, and many species have been impacted since the outbreak began in 2021.

In the winter of 2021/22, over 10,000 Barnacle Geese wintering on the Solway Firth died from the disease - between a quarter and a third of the entire Svalbard breeding population.

High numbers of dead Pink-footed Geese, Greylag Geese, Mute Swans and Whooper Swans were also reported.

Gulls and terns

In 2023, major mortality was reported for gull and tern species, which are already Red or Amber-listed in the UK because their populations are being negatively impacted by other threats.

In 2023, major mortality was reported for gull and tern species, which are already Red or Amber-listed in the UK because their populations are being negatively impacted by other threats.

Many Black-headed Gull colonies have been devastated by the virus, with an estimated 10% of the entire breeding population across the UK having died this season alone - a total of around 20,000 birds.

A more accurate report of mortality may be possible following the release of the much-awaited Seabirds Count by JNCC, which contains the most up-to-date population figures for our breeding Black-headed Gulls.

Terns have also been badly affected. Over the 2022 breeding season, almost 30% of the UK’s breeding population of Roseate Terns died from the disease.

In 2023, up to 50% of Common Terns died at major colonies and some Sandwich Terns did not return at all to sites where they were infected in 2022.

Other breeding seabirds

Together, Britain and Ireland support 25% of Europe’s breeding seabirds, including more than 50% of the world population of species which have been severely impacted by HPAI, such as Great Skua and Gannet. Population losses in the UK have a significant impact on these species’ global status.

Very large numbers of breeding seabirds have died as a result of the disease. In 2022 alone, more than 2,200 Great Skua deaths (equivalent to 11% of the British population, and 7% of the world population) were reported by NatureScot, including over 1,000 from the largest colony of Foula, Shetland.

Gannet mortalities reached the thousands in several major colonies all around the coast; over 3,000 dead adults were reported at Troup Head, Aberdeenshire, over 5,000 on Grassholm, Pembrokeshire, and over 3,100 in the Channel Islands. Reports in 2023 show that the Gannet colony at Grassholm was down by 50% but others showed much lower losses. Breeding colonies of other species, such as Guillemot, Razorbill and terns, were also impacted.

The high level of mortality that we have seen in seabird species suggests that they are very vulnerable to the disease. This could be because they have never been exposed to it before, or because the virus rapidly adapted to infect seabirds. The high mortality has greatly reduced the number of individual birds in many breeding seabird populations.

Many of these populations are already Red or Amber-listed in the UK, because their populations are being negatively impacted by other threats. They are particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change, for example. Avian influenza is only adding to the dangers these birds face.

In addition, seabirds tend to be long-lived, and slow to reach sexual maturity. This means that seabird populations can take a long time to recover from losses, because a smaller proportion of the remaining population is able to breed.

Many seabird species have evolved to lay only one or two eggs, including Guillemot, Razorbill, Great Skua and Gannet. So even among the breeding portion of the population, only one chick can be raised per pair, slowing recovery down even further.

Immunity will play a large role in determining what happens next. If, as it currently seems, the disease is endemic in the UK’s wild bird population, natural immunity from surviving the disease will build up and adult mortality will reduce in future. However, chicks will still have no immunity so we may see continuing impacts on productivity.

Raptors

The impact of avian influenza on scavenging raptors like Buzzard and Red Kite is also becoming increasingly apparent. These species will be exposed to the disease when they feed on the carcasses of birds that have died from avian influenza.

The impact of avian influenza on scavenging raptors like Buzzard and Red Kite is also becoming increasingly apparent. These species will be exposed to the disease when they feed on the carcasses of birds that have died from avian influenza.

Species such as Sparrowhawk and Kestrel are not known for scavenging but have also tested positive, and may be catching the virus from a widespread, low-level background infection in their small mammal or passerine (small bird) prey.