Buzzard

Introduction

This familiar bird of prey is often seen perched on roadside fence posts or trees, or in soaring flight over open countryside.

Our Buzzard population has shown a remarkable recovery since a low point in the middle of the 1900s, and the species may be encountered almost anywhere across Britain and the eastern half of Ireland, with the exception of urban areas and our highest peaks.

Buzzards are rather catholic in their diet, favouring whatever prey happens to be locally abundant. In addition to Rabbits and small mammals, they also take birds, amphibians, larger insects and earthworms, the latter highlighting their willingness to forage on the ground.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

ID Videos

This section features BTO training videos headlining this species, or featuring it as a potential confusion species.

Winter Buzzards: Common and Rough-legged

Summer Buzzards: Buzzard and Honey Buzzard

Eagles

Songs and Calls

Alarm call:

Flight call:

Begging call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

The Buzzard has shown a substantial eastward range expansion since the 1988-91 Atlas and is now an almost ubiquitous breeding bird in the UK (Balmer et al. 2013). For more than a decade it has been the most abundant UK raptor (Clements 2002). The increasing trend identified by the CBC relates especially to the spread of range into central and eastern Britain, where CBC was strongly represented. If anything, however, the upsurge has been amplified with the addition of the more widely representative BBS data since 1994. Results from a transect survey specifically targeting Buzzards in central southern England, between 2011 and 2016, were in line with the BBS southern region trend (Stevens, M et al. 2019). The BBS map of change in relative density between 1994-96 and 2007-09 indicates that, apart from some small pockets of decrease on Dartmoor and Exmoor, in Wales and on the Isle of Lewis, increase has occurred generally throughout the UK range. BBS suggests that numbers in Scotland and Wales are stable over the most recent 10-year period. There has been an increase across Europe since 1980, though with little change and possibly a slight decline since 1990 (PECBMS: PECBMS 2020a>). Though breeding success is still rising overall, a decrease in productivity has been documented in Avon, per pair but not per unit area, as the population has risen (Prytherch 2013) .

Distribution

Buzzards are now widespread year-round all across Britain and in the eastern half of Ireland. Densities are still lower in eastern England than elsewhere.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

The range has more than doubled and spread eastwards since the 1970s.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

Seasonality

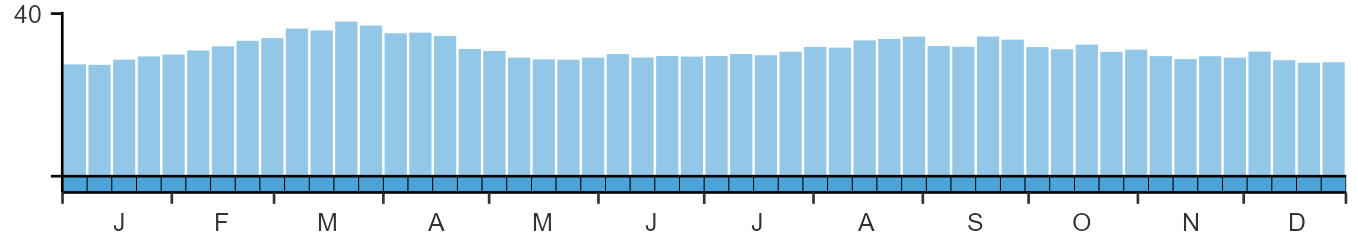

Buzzards are present year-round.

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

Habitats

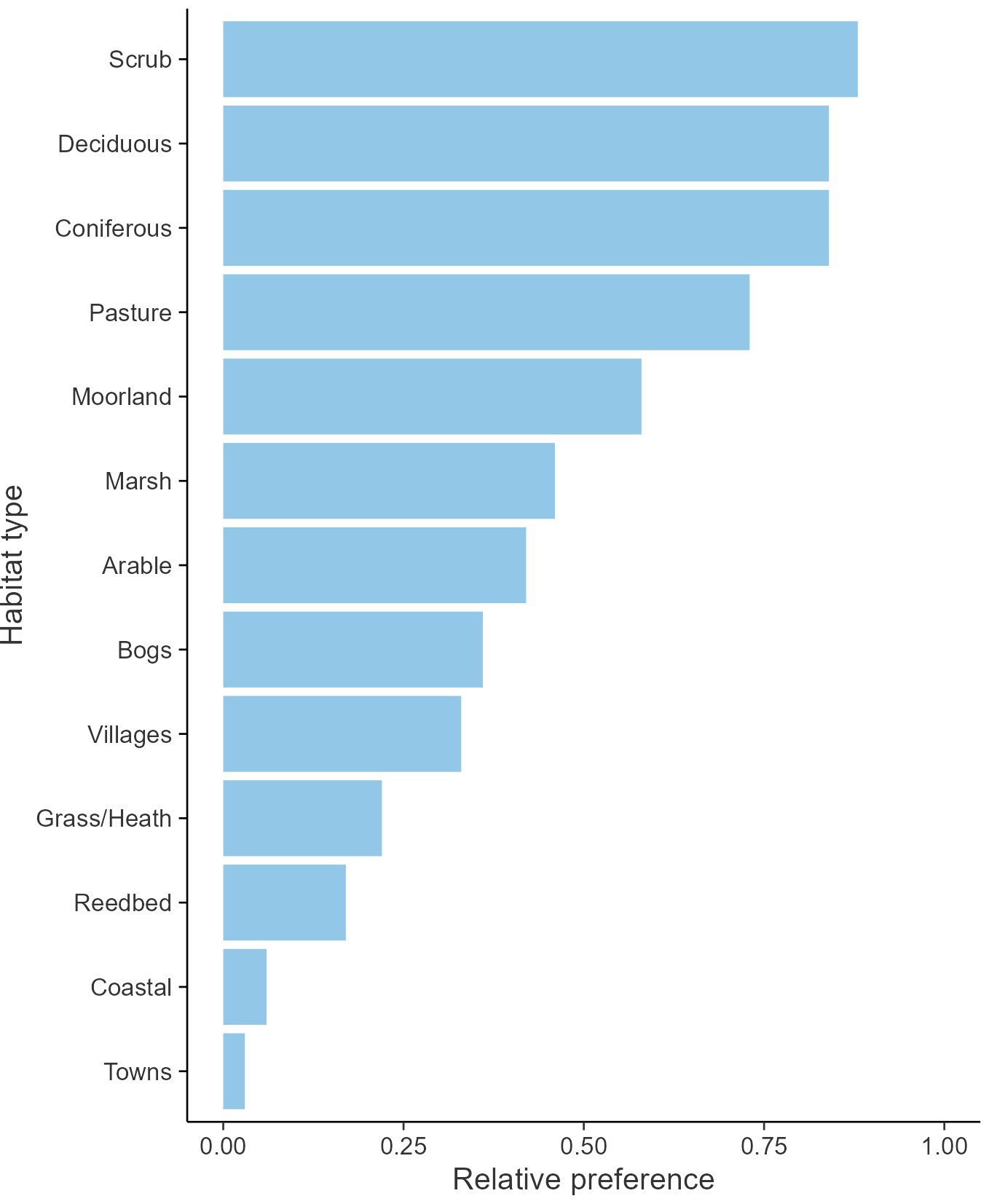

Breeding season habitats

Relative frequency by habitat

The graph shows the habitats occupied in the breeding season, with the most utilised habitats shown at the top. Bars of similar size indicate the species is equally likely to be recorded in those habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Incubation

Fledging

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

lifespan

Survival of adults

Survival of juveniles

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Accipitriformes

- Family: Accipitridae

- Scientific name: Buteo buteo

- Authority: Linnaeus, 1758

- BTO 2-letter code: BZ

- BTO 5-letter code: BUZZA

- Euring code number: 2870

Alternate species names

- Catalan: aligot comú

- Czech: káne lesní

- Danish: Musvåge

- Dutch: Buizerd

- Estonian: hiireviu

- Finnish: hiirihaukka

- French: Buse variable

- Gaelic: Clamhan

- German: Mäusebussard

- Hungarian: egerészölyv

- Icelandic: Músvákur

- Irish: Clamhán

- Italian: Poiana

- Latvian: pelu klijans

- Lithuanian: paprastasis suopis

- Norwegian: Musvåk

- Polish: myszolów (zwyczajny)

- Portuguese: águia-d'asa-redonda

- Slovak: myšiak hôrny

- Slovenian: kanja

- Spanish: Busardo ratonero

- Swedish: ormvråk

- Welsh: Bwncath

- English folkname(s): Puttock

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

There is good evidence that the increase in population numbers is associated with rapidly improving nesting success, which has been linked to reduced persecution (and therefore improved survival) and increased food supplies, for example due to the recovery of rabbit populations from the effects of myxomatosis. It is not possible to say which is the more important driver.

Further information on causes of change

As the figures above show, there has been an increase in the number of fledglings per breeding attempt and a decrease in daily failure rates at the egg stage. As such, the increase in population numbers has been associated with rapidly improving nesting success, through reduced persecution, the recovery of rabbit populations from the effects of myxomatosis and release from the deleterious effects of organochlorine pesticides (Elliott & Avery 1991, Sim et al. 2000, 2001a, Clements 2002). Numbers of Buzzard were relatively stable until the late 1980s when the population size began increasing steeply. Elliott & Avery (1991) analysed data collected by the RSPB to provide good evidence that, during 1975-89, persecution was a factor in restricting the Buzzard's range. Halley (1993) found that levels of persecution in Scotland had fallen and postulated that this was a factor in the increase in Buzzard population size. In a study of two local populations in Scotland, Swann & Etheridge (1995) provided some evidence to show that persecution was a factor in restricting population density at the site that benefited from higher productivity, although they did not specifically analyse the effects of persecution. Sim et al. (2000) provide good evidence from Buzzard populations in the West Midlands that persecution levels, especially poisonings, were lower in the 1990s when the population started increasing and state that higher survival rate due to reduced persecution was likely to be one of the main factors responsible for the rapid increase in the Buzzard population in this area. Gibbons et al. (1995) found that Buzzards were less common in the uplands where grouse moors were most frequent, stating that this was due to either persecution, unsuitable habitat management or lack of food, although did not specify which was the most important driver.

There is also good evidence to support the role of changing food availability in population increases. Graham et al. (1995) showed that Buzzard breeding density was positively related to lagomorph abundance and Swann & Etheridge (1995) found that Buzzards laid larger clutches, produced bigger broods and had significantly higher productivity where rabbits were more common. Sim et al. (2000, 2001a) also provided good evidence that increased productivity coincided with an increase in rabbit abundance. Other studies have also found that breeding success is related to food availability (Kostrzewa & Kostrzewa 1991, Austin & Houston 1997, Goszczynski 1997, 2001, Rooney et al. 2015). It is, therefore, plausible that Buzzard distribution is influenced by rabbit abundance, which has increased since rabbits have overcome the effects of myxomatosis. However, more recent declines in rabbit populations, which have been shown through BBS mammal monitoring, have not stalled the upward trend in the Buzzard population. Diet can be highly variable between years and across different geographical areas: see review in chapter 2 in Walls & Kenward (2020). A study on a Scottish grouse moor found that voles were an important prey item during both the breeding season and winter at that site, and suggested that the proportion of small mammals in prey may not necessarily be accurately estimated in studies looking at prey remains (Francksen et al. 2016a, 2016b, 2019). The same study also found that Buzzard did not switch to grouse in poor vole years (Francksen et al. 2017).

Habitat change may have played some role in the increases. High Buzzard breeding densities were associated with high proportions of unimproved pasture and mature woodland within estimated territories (Sim et al. 2000) and Sergio et al. (2002, 2005) found that Buzzard productivity benefited from the conversion of coppice woodland to mature forest in Italy. In Poland, the spread of oilseed rape has boosted vole populations (of a species not found in UK) and Buzzard productivity has correspondingly improved (Panek & Husek 2014). There is also some evidence that breeding success is related to climate, although there is little evidence for this from the UK. In Germany, Kostrzewa & Kostrzewa (1990) provide evidence to show that the number of young fledged was negatively correlated with rainfall in April and May. Although there is no evidence to support this, it is worth noting that these possible habitat/climate effects and food effects are not mutually exclusive.

Information about conservation actions

This species is currently among the fastest increasing species in the UK, and hence no specific conservation actions are currently required.

Reduced persecution is likely to have contributed to the increases, and therefore maintaining low levels of persecution may be important if the current population level is to be sustained.

There is some evidence that rabbit abundance may influence the distribution and abundance of buzzard and hence maintaining rabbit populations may also be important for this species (see Causes of Change section). However, this evidence is uncertain as Buzzards can take a wide variety of prey items including voles and even invertebrates (Walls & Kenward 2020).

Publications (2)

Long-term effects of rewilding on species composition: 22 years of raptor monitoring in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone

Author: Dombrovski, V.C., Zhurauliou, D.V. & Ashton-Butt, A.

Published: 2022

Researchers from BTO and the scientific department of Belarusian Chernobyl analysed 22 years of raptor population data from the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone (CEZ) and identified the impact of reduced human activity on some of Europe’s rarest birds of prey. Their findings demonstrate the power of rewilding for supporting biodiversity, including the conservation of vulnerable species.

19.01.22

Papers

Potential Future Distribution & Abundance Patterns of Common Buzzards Buteo Buteo

Author: Jennifer A. Border, Dario Massimino, Simon Gillings

Published: 2018

15.08.18

Reports