Mallard

Introduction

The familiar Mallard is an abundant and widespread species, found on a range of waterbodies that are still in nature and shallow in depth. These can include some brackish estuary or coastal lagoon sites.

Most of the northerly populations of this species are migratory, but our breeding birds are largely sedentary in their habits. In some parts of the country very large numbers of individuals are released to support commercial shoots.

Ringing data reveal the origins of the wintering individuals that join our resident birds; these individuals arrive from France and the Netherlands, east through the Baltic States and on into southern Finland and Russia.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

ID Videos

This section features BTO training videos headlining this species, or featuring it as a potential confusion species.

Female dabbling ducks

Songs and Calls

Call:

Flight call:

Other:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

The Mallard increased steadily as a breeding bird in the UK from the 1960s to around 2000, especially in England, with the trend levelling off since then and a shallow decline has occurred over the last ten years. The BBS map of change in relative density between 1994-96 and 2007-09 indicates that there has been increase across most of the UK but decrease in northern and western Scotland and in parts of eastern England. Winter populations have declined since at least the late 1980s (WeBS: Frost et al. 2020). The species has recently been moved from the green to the amber list on the strength of this decline in the UK wintering population. Breeding numbers have increased across Europe since 1980, which may be influenced by releases for hunting (PECBMS: PECBMS 2020a>).

Distribution

The Mallard is among the most widespread species recorded, both in the winter and in the breeding season, with records in 91% and 92% of 10-km squares respectively. This duck is really only absent from the most remote mountainous areas and from squares with no suitable aquatic habitats.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

Seasonality

Mallards are a common and widespread resident, recorded year-round.

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

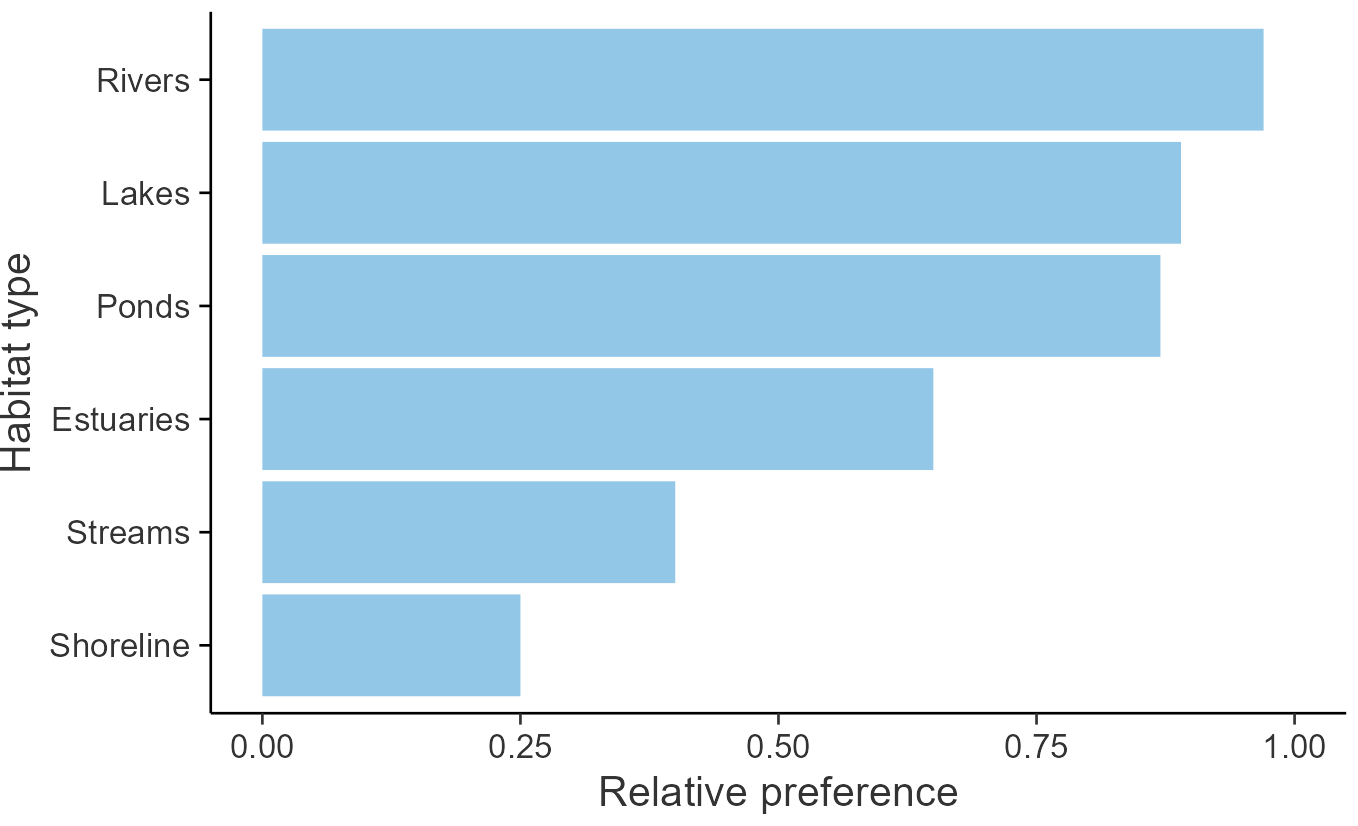

Habitats

Breeding season habitats

Relative frequency by habitat

The graph shows the habitats occupied in the breeding season, with the most utilised habitats shown at the top. Bars of similar size indicate the species is equally likely to be recorded in those habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

lifespan

Survival of adults

Survival of juveniles

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Anseriformes

- Family: Anatidae

- Scientific name: Anas platyrhynchos

- Authority: Linnaeus, 1758

- BTO 2-letter code: MA

- BTO 5-letter code: MALLA

- Euring code number: 1860

Alternate species names

- Catalan: ànec collverd

- Czech: kachna divoká

- Danish: Gråand

- Dutch: Wilde Eend

- Estonian: sinikael-part

- Finnish: sinisorsa

- French: Canard colvert

- Gaelic: Lach-riabhach

- German: Stockente

- Hungarian: tokés réce

- Icelandic: Stokkönd

- Irish: Mallard

- Italian: Germano reale

- Latvian: meža pile

- Lithuanian: didžioji antis

- Norwegian: Stokkand

- Polish: krzyzówka

- Portuguese: pato-real

- Slovak: kacica divá

- Slovenian: mlakarica

- Spanish: Ánade azulón

- Swedish: gräsand

- Welsh: Hwyaden Wyllt

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

There is little good evidence available regarding the drivers of the breeding population increase in this species in the UK.

Further information on causes of change

Information about demographic trends is very sparse for this species and there is very little evidence generally relating to the causes of the population increases in the UK.

Mallards originating from domesticated birds and not resembling wild-type birds in either plumage or behaviour are very abundant but perhaps under-represented in survey data, especially since many individuals might appear to be semi-captive. A large part of the increase in breeding numbers may be attributable to such birds, rather than to true-bred stock. It is also likely that increases may be at least partly attributable to ongoing large-scale releases for shooting (Marchant et al. 1990). In a study in central France, Champagnon et al. (2016), found that overall survival rate of released birds was low, and equivalent to half the first-year survival of wild Mallards in the same area. Nonetheless, they estimated that a minimum of 34% of the Mallards in the region at the start of the next breeding season were of captive origin.

Declines in wintering numbers have been linked to a decrease in continental immigration (Mitchell et al. 2002, Sauter et al. 2010). The effects of ingested lead gunshot has also been identified as a possible cause of declines in wintering numbers. Analysis of the trends for eight duck species, including Mallard, identified a significant negative correlation between levels of ingested lead gunshot and population changes, and did not find any evidence to support a link to decreased immigration (Green & Pain 2016 1990). Guillemain et al. (2010) found trends of increasing average body mass of Mallard in France which were large enough to have major fitness consequences with respect to winter survival, suggesting that overwinter survival has not decreased. Overwinter loss was investigated in Mallard at 35 inland waters in the Midlands and southern England (Hill 1984). Duckling mortality was the key factor, explaining 58% of total mortality between years and this was weakly density dependent. Overwinter loss was higher following years when a large number of young were produced and was the main regulatory factor.

Information about conservation actions

The recent breeding trend for this species has been relatively stable following previous increases although the wintering numbers have been declining since the 1980s. As for other wetland species ongoing local site management actions to maintain favourable conservation status are likely to support the Mallard. These might include the creation of new wetland habitats such as gravel pits, the creation of nesting sites such as islands and the ongoing management of existing habitats through ensuring that water quality is monitored, and that suitable good quality wetland habitat is maintained.

Whilst site management will provide nesting habitat at individual sites, landscape scale approaches which plan management activity and the creation of a network of sites over a wider area can lead to a greater-than-proportional increase in Mallard abundance (Newbold & Eadie 2004). Therefore, policies which encourage a landscape scale approach to wetland creation and management should be preferred.

The spread of domesticated birds into the wild breeding population could be a potential threat to this species as it may lead to hybridization and a loss of pure native stock, and large numbers of birds descended from domestic stock may already be present in the wild in Europe ( Cizkova et al. 2012). It is unclear what action can be taken apart from attempting to prevent new introductions wherever possible, as it is not always straightforward to recognise hybrids (Simberloff 1996).

Habitat creation and management is also likely to benefit wintering Mallards. Declines in wintering numbers have been attributed to a decrease in immigration from the continent, with birds tending to winter further north and east as a result of climate change (Mitchell et al. 2012; Sauter et al. 2010), with the effects of ingested lead gunshot another possible contributory factor. Conservation actions and policies to encourage shooters to replace lead gunshot with alternatives are therefore another measure which may help to reduce the UK decline (Green & Pain 2016). The provision of refuges from hunting may also help wintering Mallards (Evans & Day 2002). If the main driver of change is changing migration patterns, these actions may only slow the UK decline rather than reversing it, but will also help to ensure that the European breeding population is maintained.

Publications (1)

High pathogenicity avian influenza: Targeted active surveillance of wild birds to enable early detection of emerging disease threats

Author: Wade, D., Ashton-Butt, A., Scott, G., Reid, S., Coward, V., Hansen, R.D.E., Banyard, A.C. & Ward, A.

Published: 2022

The disease Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) has caused significant damage to both wild bird populations and the poultry industry. Detection of the disease has tended to rely on the sampling of dead birds following the reporting of mortality events, but could a different approach provide advance warning of potential outbreaks?

11.12.22

Papers