Oystercatcher

Introduction

The Oystercatcher is a striking and familiar wader, its pied plumage contrasting with the bright orange bill and pinkish legs.

The species breeds widely, both around the coast and inland, particularly in northern Britain, whilst during winter large flocks congregate on our estuaries. In Ireland the breeding population remains predominantly coastal. Britain & Ireland support a significant proportion of the global population of this species.

Ringing studies highlight that there is little interchange between the Atlantic subpopulation – which includes those breeding in Iceland, the Faeroes, Britain and Ireland – and the continental subpopulation, which is made up of birds from Scandinavia and the Low Countries.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

Songs and Calls

Song:

Call:

Alarm call:

Flight call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

Oystercatchers increased along linear waterways between 1974 and about 1986, as the species colonised inland sites across England and Wales (Gibbons et al. 1993). Thereafter, the WBS/WBBS index stabilised and now appears to be in decline, so showing a pattern similar to that in winter abundance (WeBS: Frost et al. 2020). Surveys in England and Wales revealed an increase of 47% in breeding birds in wet meadows between 1982 and 2002 (Wilson et al. 2005). BBS data since 1995, which include birds in a broader range of locations and habitats, show a moderate increase in England but a significant, moderate decline in Scotland. There has been a decline across Europe since 1980 (PECBMS: PECBMS 2020a>).

Distribution

In winter, Oystercatchers are widely distributed on rocky and estuarine shores, with the largest concentrations forming on the major estuaries. They breed around most of the UK coast and are nearly ubiquitous across the interior of Scotland except for some northwestern upland areas and have recently spread into the interior of northern and eastern England.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

Since the 1970s there has been a 28% range expansion in Britain, but little change in Ireland. Gains in Britain are almost exclusively at inland sites.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

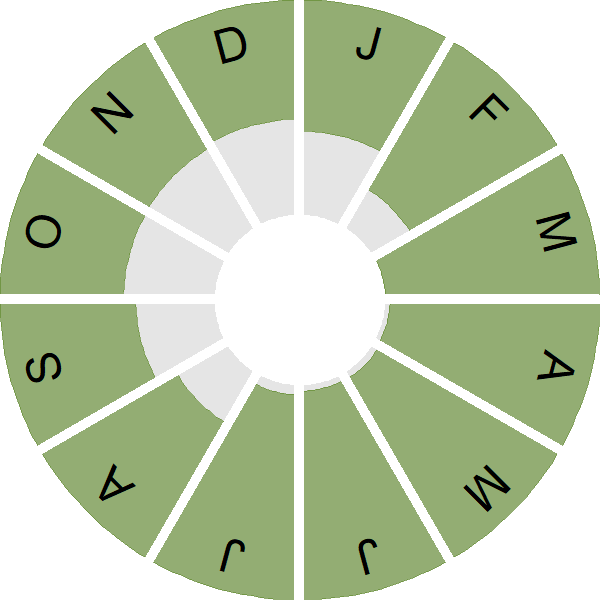

Seasonality

Oystercatchers are recorded throughout the year but encountered more widely in spring and summer when birds are less confined to the coast.

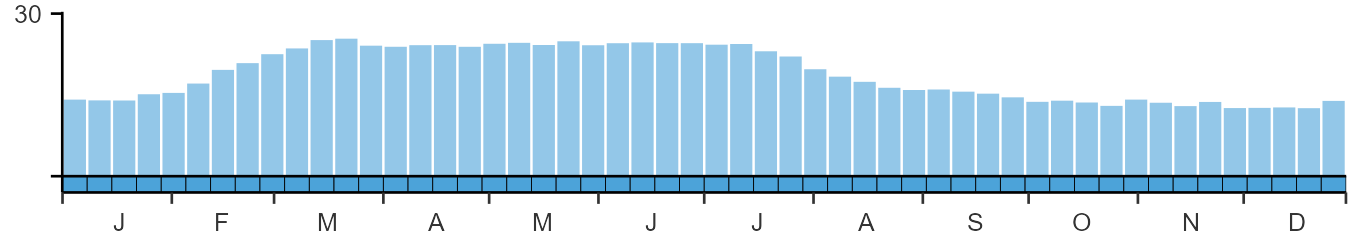

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

Habitats

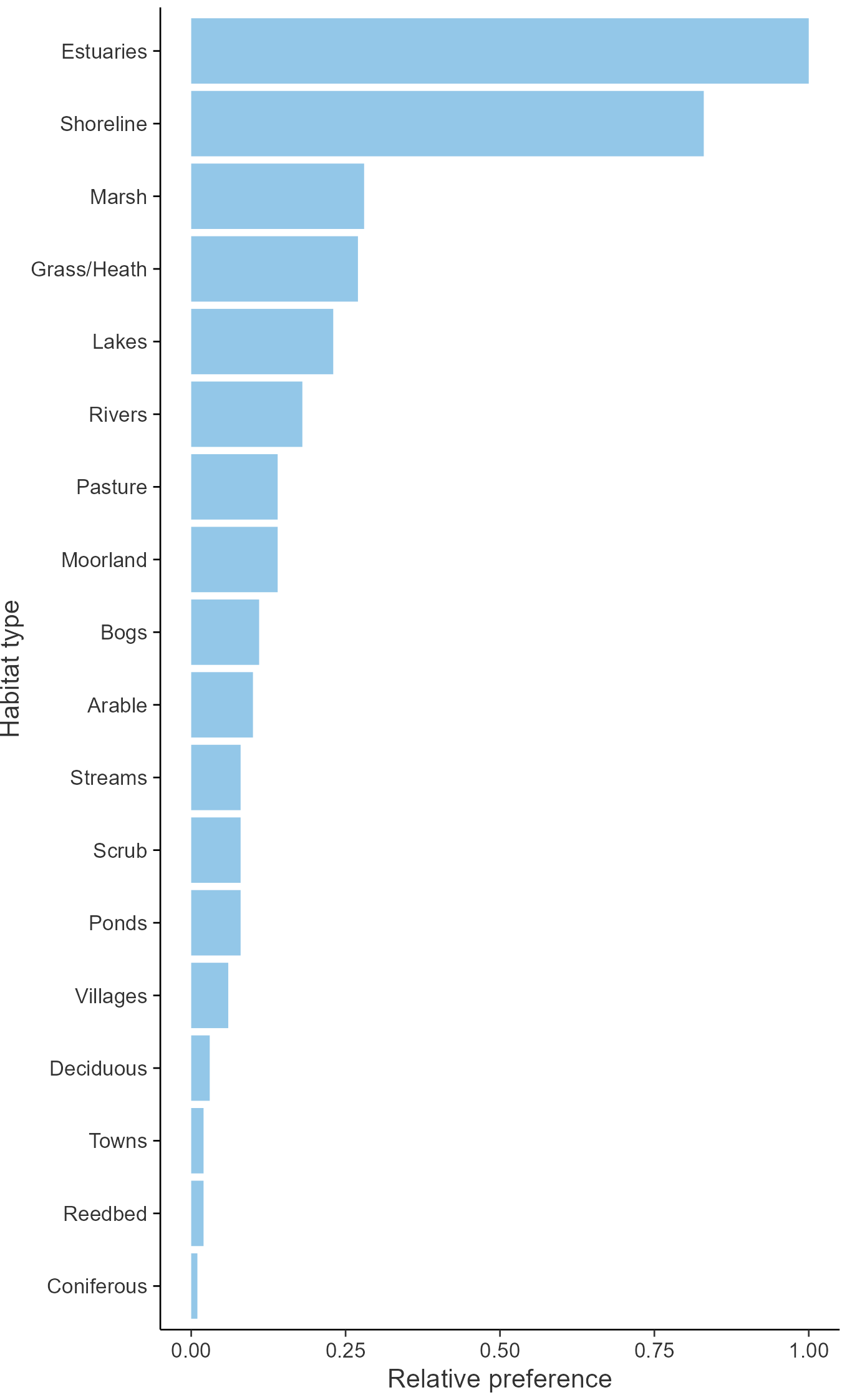

Breeding season habitats

Relative frequency by habitat

The graph shows the habitats occupied in the breeding season, with the most utilised habitats shown at the top. Bars of similar size indicate the species is equally likely to be recorded in those habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

lifespan

Survival of adults

Survival of juveniles

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Charadriiformes

- Family: Haematopodidae

- Scientific name: Haematopus ostralegus

- Authority: Linnaeus, 1758

- BTO 2-letter code: OC

- BTO 5-letter code: OYSTE

- Euring code number: 4500

Alternate species names

- Catalan: garsa de mar

- Czech: ústricník velký

- Danish: Strandskade

- Dutch: Scholekster

- Estonian: merisk

- Finnish: meriharakka

- French: Huîtrier pie

- Gaelic: Gille-Brìghde

- German: Austernfischer

- Hungarian: csigaforgató

- Icelandic: Tjaldur

- Irish: Roilleach

- Italian: Beccaccia di mare

- Latvian: juras žagata

- Lithuanian: eurazine juršarke

- Norwegian: Tjeld

- Polish: ostrygojad (zwyczajny)

- Portuguese: ostraceiro

- Slovak: lastúrniciar strakatý

- Slovenian: školjkarica

- Spanish: Ostrero euroasiático

- Swedish: strandskata

- Welsh: Pioden Fôr

- English folkname(s): Sea Pie

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

The main causes of the recent decline are unclear.

Further information on causes of change

The increase in nest failure rates during the 27-day egg stage (25 days for incubation and 2 days for laying) probably results from the spread of the species into less favourable habitats, where nest losses through predation or trampling may be more likely. A 95% decline over 1990-2015 at a study area in Perthshire, Scotland, was attributed to land use and crop type changes (Bell & Calladine 2017). The trend towards earlier laying may be linked to recent climate change (Crick & Sparks 1999).

Information about conservation actions

The causes of the recent decline are unclear and hence conservation requirements are also uncertain. Oystercatchers breed in wetland habitat both along the coast and inland, and therefore actions to improve breeding habitat for other waders may also improve breeding success for Oystercatchers. These could include maintaining and restoring saltmarsh and other wetland habitats, less intensive management of grasslands (including reduced drainage to raise water) and delaying mowing of grasslands in which waders are breeding.

Declines in the Netherlands have been attributed to over-exploitation by shell-fisheries in the Wadden Sea and hence reduced survival during winter (van de Pol et al. 2014). Exploitation of shellfish has also affected some sites in the UK (e.g. Norris et al. 1998; Atkinson et al. 2003), although it is unclear if the UK population declines have been caused by it. However, the majority of the UK breeding population winters around the UK coast, with many estuaries holding protected status as they support nationally and internationally important numbers of Oystercatchers and other wetland species during winter. Appropriate management of shellfish numbers at key wintering sites is therefore likely to be important for this species, along with other policies to ensure these sites continue to be protected and habitat quality maintained or improved (e.g. Goss-Custard et al. (2019).

Publications (11)

Decline in the numbers of Eurasian Oystercatchers Haematopus ostralegus on the Exe estuary Special Protection Area

Author: Goss-Custard, J.D., Austin, G.E., Frost, T.M., Sitters, H.P. & Stillman, R.A.

Published: 2024

The Exe Estuary in Devon is a nationally important site for Oystercatchers wintering in the UK. However, the proportion of this species found in south-west England and wintering on the Exe declined from 60% in the late 1980s to 35% by the late 2010s. This study uses 45 years of data collected by volunteers taking part in the Wetland Bird Survey (WeBS) to investigate why.

07.11.24

Papers

How effective has the management of Cockle and Mussel fisheries on The Wash estuary been in ensuring that there is sufficient food for birds?

Author: Kirkland, M., Atkinson, P.W., Clark J.A. & Robinson, R.A.

Published: 2024

The Wash is England’s largest Special Protection Area, with Oystercatchers being a designated feature. During the winter, Oystercatchers rely heavily on Cockles and Blue Mussels for their food requirements, creating the potential for conflict with the human fisheries for these species.

10.07.24

Reports Research reports

Changes in breeding wader populations of the Uist machair and adjacent habitats between 1983 and 2022

Author: Calladine, J., Fuller, R., Hodkinson, D., Franks, S. & Boyle, J.

Published: 2023

Periodic surveys of machair and associated habitats on the west coast of North Uist, Benbecula and South Uist have documented marked changes in the composition of an important breeding wader assemblage. Within the study area of there was a 25% decline in the total number of breeding waders recorded between 1983 and 2022.

15.06.23

Papers

Modelling important areas for breeding waders as a tool to target conservation and minimise conflicts with land use change

Author: Calladine, J., Border, J., O’Connell, P. & Wilson, M.

Published: 2022

The future of Britain’s breeding wader populations depends on land use policy and local management decisions, both of which require robust evidence and appropriate tools if they are to support the conservation of these priority species. One of the biggest challenges has been the geographical scale at which national data on wader abundance and distribution are available. These data are coarse in their resolution, making them poorly suited to directing conservation initiatives or informing land management decisions at a local scale. But can a statistical approach produce high-resolution maps of predicted wader abundance that are sufficiently accurate to be used for decision-making?

27.09.22

Papers

Sensitivity mapping for breeding waders in Britain: towards producing zonal maps to guide wader conservation, forest expansion and other land-use changes. Report with specific data for Northumberland and north-east Cumbria

Author: O’Connell, P., Wilson, M., Wetherhill, A. & Calladine, J.

Published: 2021

Breeding waders in Britain are high profile species of conservation concern because of their declining populations and the international significance of some of their populations. Forest expansion is one of the most important, ongoing and large-scale changes in land use that can provide conservation and wider environmental benefits, but also adversely affect populations of breeding waders. We describe models to be used towards the development of tools to guide, inform and minimise conflict between wader conservation and forest expansion.Extensive data on breeding wader occurrence is typically available at spatial scales that are too coarse to best inform waderconservation and forestry stakeholders. Using statistical models (random forest regression trees) we model the predicted relative abundances of 10 species of breeding wader across Britain at 1-km square resolution. Bird data are taken from Bird Atlas 2007–11, which was a joint project between BTO, BirdWatch Ireland and the Scottish Ornithologists’ Club, and modelled with a range of environmental data sets.

09.12.21

Reports Research reports

Pilot study to investigate Oystercatcher (Haematopus ostralegus) feeding behaviour to enhance bird food modelling and shellfisheries management on The Wash

Author: Clewley, G.D., Franks, S.E., Clark, N.A. & Robinson, R.A.

Published: 2021

26.04.21

Reports

Monitoring Breeding Waders in Wensleydale: trialling surveys carried out by farmers and gamekeepers

Author: Jarrett, D., Calladine, J., Wernham, C., Wilson, M.

Published: 2017

21.11.17

Reports

Consequences of population change for local abundance and site occupancy of wintering waterbirds

Author: Méndez, V., Gill, J.A., Alves, J.A., Burton, N.H.K. & Davies, R.G.

Published: 2017

Protected sites for birds are typically designated based on the site’s importance for the species that use it. For example, sites may be selected as Special Protection Areas (under the European Union Directive on the Conservation of Wild Birds) if they support more than 1% of a given national or international population of a species or an assemblage of over 20,000 waterbirds or seabirds. However, through the impacts of changing climates, habitat loss and invasive species, the way species use sites may change. As populations increase, abundance at existing sites may go up or new sites may be colonized. Similarly, as populations decrease, abundance at occupied sites may go down, or some sites may be abandoned. Determining how bird populations are spread across protected sites, and how changes in populations may affect this, is essential to making sure that they remain protected in the future.

20.09.17

Papers

The decline of a population of farmland breeding waders: a twenty-five-year case study

Author: M.V. Bell, Calladine, J.

Published: 2017

The breeding populations of many different wader species are in decline across the globe, and the UK is no exception. These declines have been linked to increased predator numbers, changes in agricultural practices, and in the management of the wider landscape. There is an urgent need for information on how such changes in land management, particularly within farmland, may affect breeding waders. This information can then be used to inform future land management decisions.

12.04.17

Papers Bird Study

Oystercatcher starvation on the Wash - a case of poor food supplies

Author: Clark, N.A.

Published: 1995

01.01.95

Papers

Differential distribution of Oystercatchers Haematopus ostralegus overwintering on the Wash, east England

Author: Dit Durell, S.E.A.le V. & Atkinson, P.W.

Published: 2004

01.01.04

Papers Bird Study