Sand Martin

Introduction

The smallest of our hirundines, the Sand Martin can be found nesting in colonies in sandy banks across Britain & Ireland.

The Sand Martin is amongst our earliest summer visitors to arrive, often being seen during the first two weeks of March. It is also one of our earliest to go again, with most birds leaving the country in early September, heading for wintering locations south of the Sahara. Compared to House Martins, Sand Martins have a plainer appearance, with mostly brown plumage apart from a white chin and belly.

A long-distance migrant to our shores, ringed Sand Martins have been shown to cover distances in excess of 4,000 km between the UK and their wintering locations. UK Sand Martin numbers have fluctuated in recent decades, but a recent uptick led to them being moved from the Amber to the Green List in 2015. In the breeding season, Sand Martins can be found across Britain & Ireland.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

ID Videos

This section features BTO training videos headlining this species, or featuring it as a potential confusion species.

Hirundines & Swift

Songs and Calls

Call:

Alarm call:

Flight call:

Begging call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

This species is unusually difficult to monitor, because active and inactive nest holes are difficult to distinguish, and because whole colonies frequently disperse or shift to new locations as suitable sand cliffs are created and destroyed. WBS counts were of apparently occupied nest holes along riverbanks but BBS and WBBS record birds seen. WBS/WBBS suggests a stable or shallowly increasing population, with wide fluctuations, although the decrease during the late 1990s and early 2000s was steep enough to raise BTO alerts in previous reports. BBS counts also show that large year-to-year changes occur, but do not yet reveal a clear long-term trend. Though previously amber listed through its 'depleted' status in Europe, the species was moved to the UK green list in 2015 (Eaton et al. 2015).

Distribution

Breeding Sand Martins occur throughout Ireland whereas in Britain they are localised south of a line from the Wash to the Severn Estuary. They remain scarce in the Outer Hebrides and are absent from Shetland.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

In Wales and Ireland Sand Martin range has been relatively stable. In Scotland there are range extensions into the northwest and onto some of the Inner Hebrides and to Orkney. Abundance has increased in Ireland, Scotland and northern England but decreased across much of southern England.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

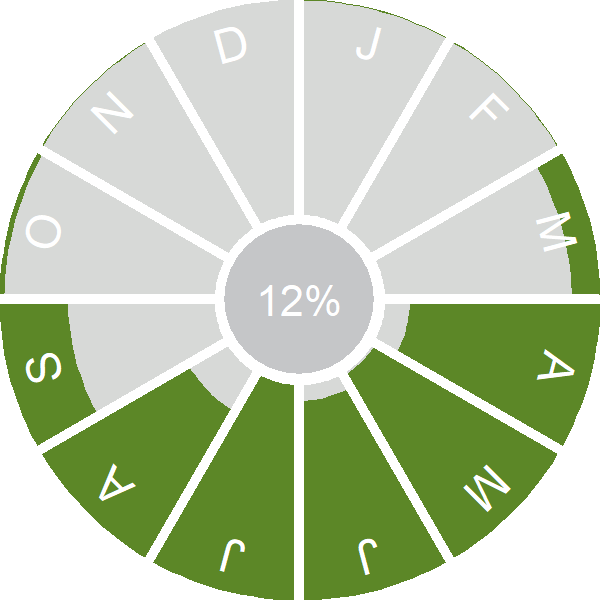

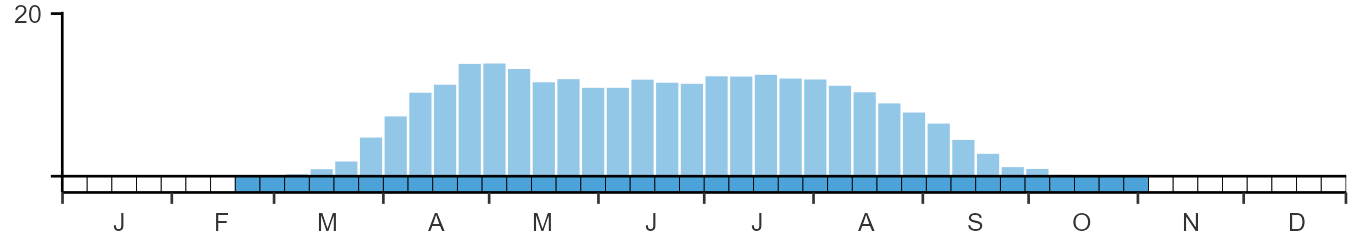

Seasonality

Sand Martin is one of the earliest summer visitors, arriving from mid March onwards, departing through August and September.

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

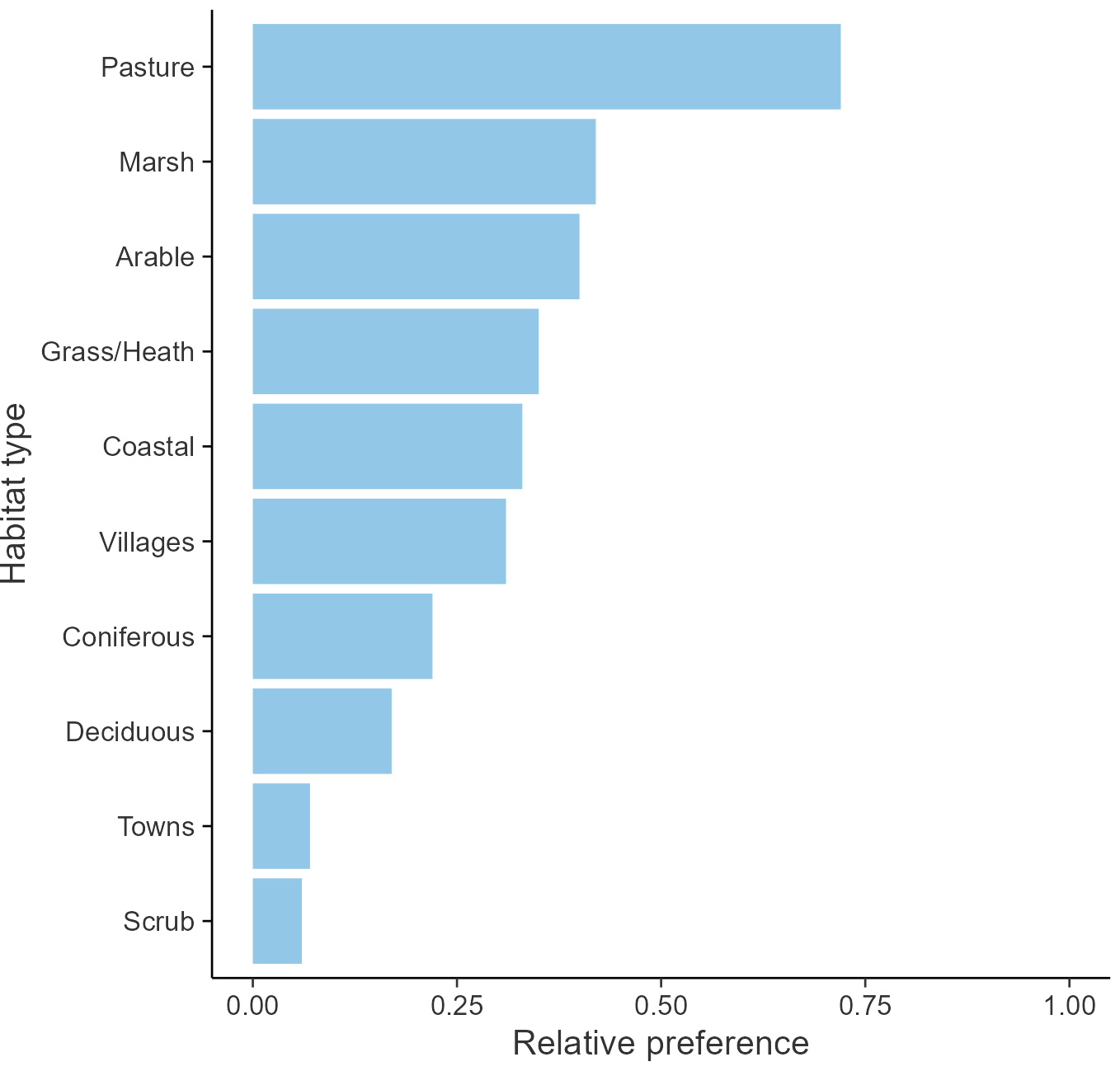

Habitats

Breeding season habitats

Relative frequency by habitat

The graph shows the habitats occupied in the breeding season, with the most utilised habitats shown at the top. Bars of similar size indicate the species is equally likely to be recorded in those habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Incubation

Fledging

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

lifespan

Survival of adults

Survival of juveniles

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Passeriformes

- Family: Hirundinidae

- Scientific name: Riparia riparia

- Authority: Linnaeus, 1758

- BTO 2-letter code: SM

- BTO 5-letter code: SANMA

- Euring code number: 9810

Alternate species names

- Catalan: oreneta de ribera comuna

- Czech: brehule rícní

- Danish: Digesvale

- Dutch: Oeverzwaluw

- Estonian: kaldapääsuke

- Finnish: törmäpääsky

- French: Hirondelle de rivage

- Gaelic: Gobhlan-gainmhich

- German: Uferschwalbe

- Hungarian: partifecske

- Icelandic: Bakkasvala

- Irish: Gabhlán Gainimh

- Italian: Topino

- Latvian: krastu curkste

- Lithuanian: paprastoji urvine kregžde

- Norwegian: Sandsvale

- Polish: brzegówka (zwyczajna)

- Portuguese: andorinha-do-barranco / andorinha-das-barreiras

- Slovak: brehula hnedá

- Slovenian: breguljka

- Spanish: Avión zapador

- Swedish: backsvala

- Welsh: Gwennol y Glennydd

- English folkname(s): Water Swallow

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

The main drivers of change are uncertain. The number of fledglings per breeding attempt has not changed although this is based on a small sample. There is some evidence that population changes may be linked to overwinter survival but the ecological processes for this are unclear and the findings from different studies have sometimes been inconsistent.

Further information on causes of change

Arrival dates in the UK advanced by over three weeks between the 1960s and the 2000s (Newson et al. 2016), but laying dates have not changed so it is unclear whether this may have an effect on the population. Nest-record samples are small, but indicate that nest failure rates have decreased enormously since the 1960s; however brood size has also decreased and no trend can be detected in the numbers of fledglings per breeding attempt.

Rainfall in the species' trans-Saharan wintering grounds prior to the birds' arrival promotes annual survival and thus abundance in the following breeding season (Szep 1995). A study in Italy found that, since around 2000, this link no longer held there, perhaps because more recent wintering conditions had been less extreme, although the data suggested that there may still be some weak influence of winter climate on survival (Masoero et al. 2016). However, another recent study confirmed that winter climate and conditions on passage were still the main drivers of breeding abundance at a site in Lancashire (Mondain-Monval et al. 2020). Annual survival rates from RAS sites in the UK for 1990-2004 were correlated positively with minimum monthly rainfall during the wet season in West Africa (Robinson et al. 2008). Mark-recapture in Cheshire during 1981-2003 found that, after allowing for the effects of African rainfall, some demographic measures were density dependent, with adult survival low when wintering densities (measured as the size of the western European population) were high and recruitment low when the local Cheshire population was high (Norman & Peach 2013). This study did not replicate an earlier finding (Cowley & Siriwardena 2005) that summer rainfall on the breeding grounds has a negative influence on survival rates through the following winter.

Information about conservation actions

The drivers of change for this species are uncertain, but may relate at least in part to conditions in wintering areas; hence it is unclear whether conservation actions taken in the UK will have any significant effect on the population.

However, the building of artificial sandbanks and nest holes to provide nesting habitat for Sand Martins has successfully attracted them to breed at sites in the UK (Hopkins 2001). Another method which has been used successfully to create artificial burrows is by drilling holes, e.g. into a limestone cliff (Gulickx et al. 2007).