Skylark

Introduction

As one of our most celebrated birds, in literature, poetry, art and music, the Skylark hardly needs an introduction.

The Skylark is one of 19 species that make up the UK Farmland Bird Indicator. As a group, these species are amongst our most declining birds, and Skylark numbers have fallen precipitously since the mid-1970s. However, the latest UK population trend indicates a small upturn in this species' fortunes.

The Skylark is found across Britain & Ireland and can be heard singing its song on high at any time of the year on sunny days. In the summer months, the song of the Skylark becomes a force of nature, whilst in the winter Skylarks often gather in large flocks on farmland, saltmarsh and dunes. Skylarks can lay up to four clutches a year, but this has likely been limited by agricultural intensification in recent decades, and the switch from spring to autumn crop sowing in particular. This switch may also reduce overwinter survival due to loss of winter stubbles.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

ID Videos

This section features BTO training videos headlining this species, or featuring it as a potential confusion species.

Skylark & Woodlark

Meadow Pipit, Tree Pipit & Skylark

Songs and Calls

Song:

Alarm call:

Flight call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

The Skylark declined rapidly from the mid 1970s until the mid 1980s, when the rate of decline slowed. BBS data show further decline, with fluctuations in Scotland and Wales. The BBS map of change in relative density between 1994-96 and 2007-09 indicates that decrease was severe in Northern Ireland and eastern England but that numbers rose in Scotland during that period, especially in the northwest. There has been a decline across Europe since 1980 (PECBMS: PECBMS 2020a>).

Distribution

In winter, Skylarks are widespread throughout Britain, except at higher altitudes; densities are highest in the south and east of England and in coastal areas. In Ireland, they are sparsely distributed, favouring southern, eastern and coastal regions. The range expands to the uplands in the breeding season and Skylarks become widespread throughout Britain and most of Ireland. Densities are relatively high in the lowlands, particularly in eastern Britain, in the lower hills of western England and Wales, and along the western coastal fringes of Scotland and Ireland.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

Despite many decades of breeding population decline lossed have not yet been severe enough to generate range losses in Britain. However, in Ireland there was a substantial range contraction of 14% between 1968–72 and 2008–11

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

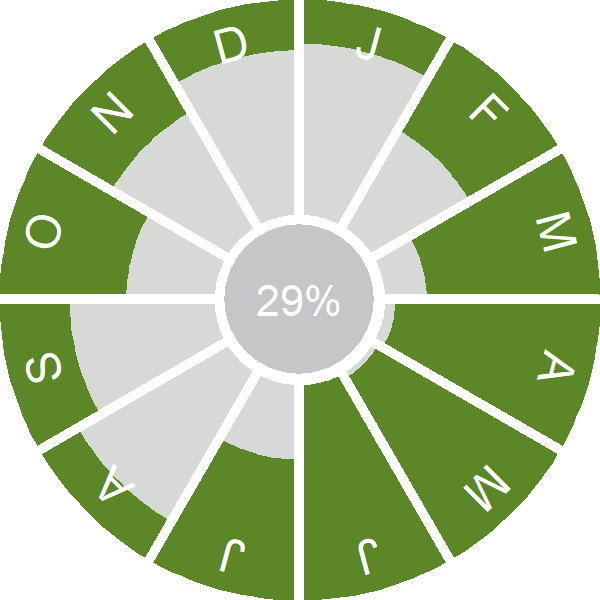

Seasonality

Skylarks are present throughout the year but most often detected in spring/summer when singing and in autumn during daytime visible migration; noticeably low recording during late summer moult.

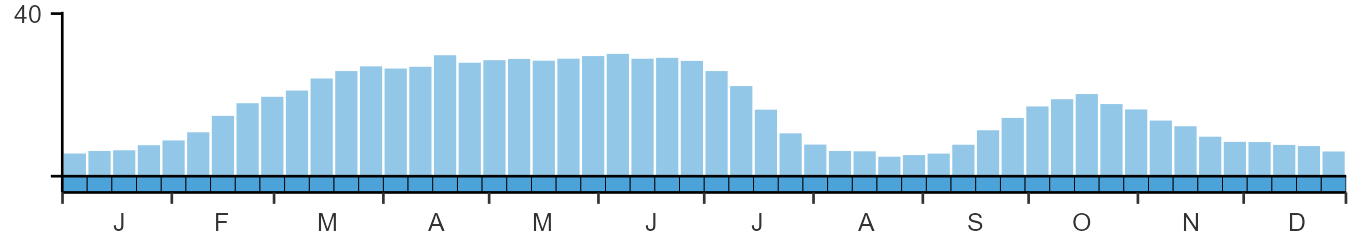

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

Habitats

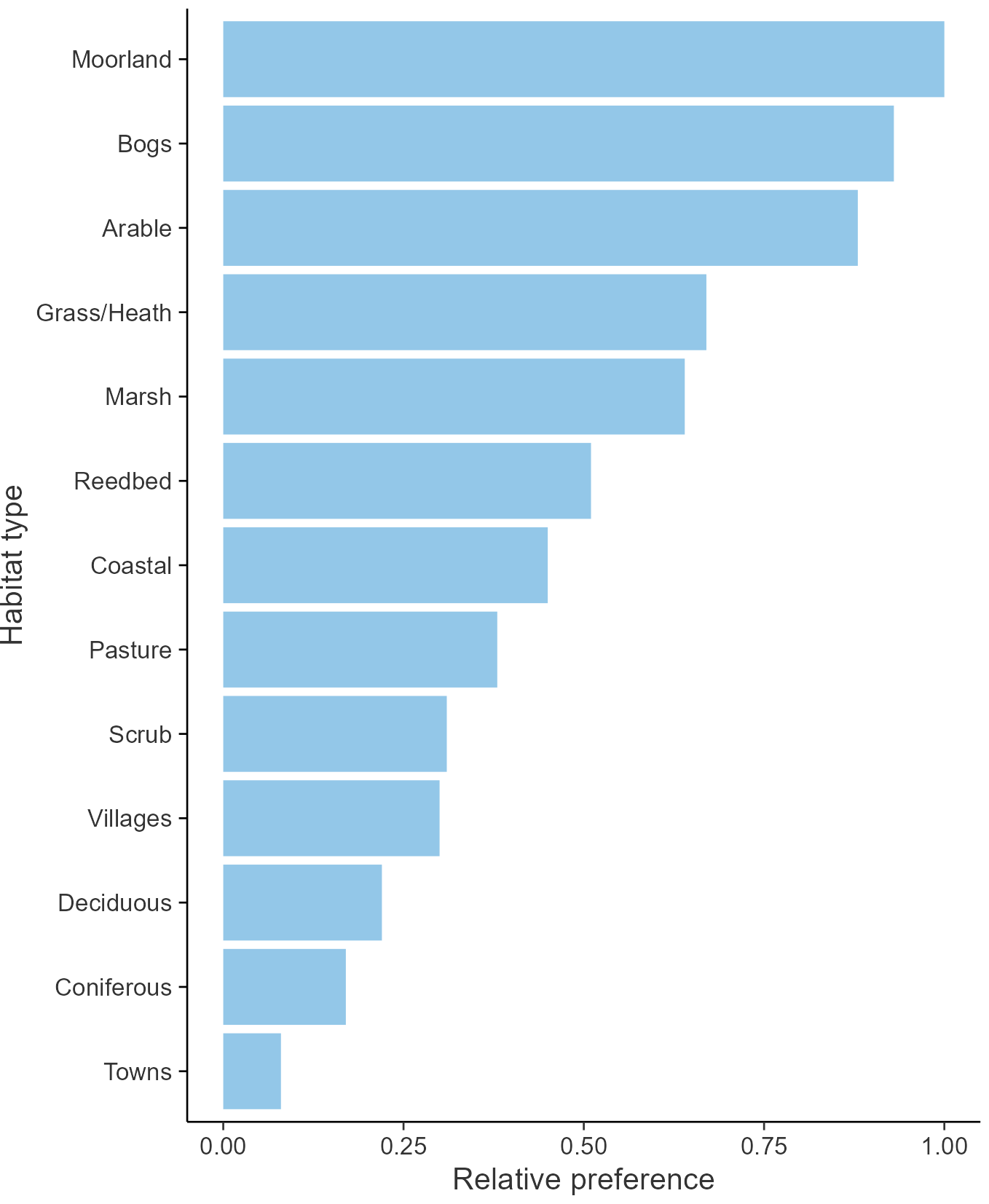

Breeding season habitats

Relative frequency by habitat

The graph shows the habitats occupied in the breeding season, with the most utilised habitats shown at the top. Bars of similar size indicate the species is equally likely to be recorded in those habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Incubation

Fledging

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

lifespan

Survival of adults

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Passeriformes

- Family: Alaudidae

- Scientific name: Alauda arvensis

- Authority: Linnaeus, 1758

- BTO 2-letter code: S.

- BTO 5-letter code: SKYLA

- Euring code number: 9760

Alternate species names

- Catalan: alosa comuna

- Czech: skrivan polní

- Danish: Sanglærke

- Dutch: Veldleeuwerik

- Estonian: põldlõoke

- Finnish: kiuru

- French: Alouette des champs

- Gaelic: Uiseag

- German: Feldlerche

- Hungarian: mezei pacsirta

- Icelandic: Sönglævirki

- Irish: Fuiseog

- Italian: Allodola

- Latvian: lauku cirulis

- Lithuanian: dirvinis vieversys

- Norwegian: Sanglerke

- Polish: skowronek (zwyczajny)

- Portuguese: laverca

- Slovak: škovránok polný

- Slovenian: poljski škrjanec

- Spanish: Alondra común

- Swedish: sånglärka

- Welsh: Ehedydd

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

There is good evidence to indicate that the most likely cause of declines in Skylark is agricultural intensification, specifically the change from spring to autumn sowing of cereals, which reduces the number of breeding attempts possible and may also reduce overwinter survival due to loss of winter stubbles.

Further information on causes of change

Demographic trends presented here show that an increase in clutch and brood sizes and a decrease in the daily failure rate of nests at the chick stage until the 1990s, since partially reversed; the number of fledglings per breeding attempt has not changed. Chamberlain & Crick (1999) and Siriwardena et al. (2000b) found that breeding success per nesting attempt increased during the steepest period of decline, suggesting that these demographic changes have not contributed to the causes of population decline. The available data do not allow tests for effects of survival. Conversely, it is easy to test for effects on breeding success, especially locally and with respect to contemporary as opposed to historical land use. This creates a big imbalance in the amounts of evidence available.

Agricultural intensification has been put forward as the ultimate cause of Skylark declines. The relevant changes in agriculture have been decreases in preferred crops (spring cereals and cereal stubble) and an increase in unfavourable habitats (winter cereals, oilseed rape and intensively managed or grazed grass) (Chamberlain & Siriwardena 2000). There is good evidence that the most likely cause of the decline is the change from spring to autumn sowing of cereals. This practice restricts opportunities for late-season nesting attempts, because the crop is by then too tall. Chamberlain et al. (2000a) used habitat data from CBC surveys to show that the occurrence of autumn-sown, winter cereals increased from 33% to 78% between 1965 and 1995. Evans et al. (1995) and Wilson et al. (1997) all found that Skylarks deserted areas of autumn-sown crops as soon the sward reached a critical height, which occurred before the end of the breeding season. Jenny (1990), Chamberlain et al. (1999, 2000a, 2000b) and Donald & Vickery (2000) all recorded low and seasonally declining densities of Skylarks in cereals and suggested that this was at least partly due to the effects of changing vegetation structure. As well as preventing nesting, crop development also influences the positioning of the nests and hence their productivity: as the crop develops the birds are forced to nest closer to tramlines with a consequent increase in nest predation rate (Donald & Vickery 2000, Morris & Gilroy 2008). Skylark plots in crop fields have been found to support higher densities of breeding pairs (Schmidt et al. 2017) and may have the potential to help reverse population declines, but further research is needed on this subject.

Analyses by Chamberlain & Crick (1999) provided detailed evidence from both regional and habitat-based analyses that the greatest declines in Skylark numbers were associated with agricultural habitat, although their evidence suggests that different patterns of decline were unlikely to be due to differences in breeding success per attempt between habitats. However, Siriwardena et al. (2001) showed that the population trend can be explained by national changes in crop areas, together with a cold winter in 1981/82.

There is also some evidence that the increase in autumn sowing may depress overwinter survival by reducing the area of stubbles (Wilson et al. 1997, Donald & Vickery 2000, 2001). Donald & Vickery (2001) used data from BTO and RSPB studies to show that, in winter, cereal stubbles were strongly selected by Skylarks, probably owing to the presence of spilt grain and regenerating weeds, and go on to state that the area of stubbles has declined greatly in recent years. Gillings et al. (2005) identified better population performance in areas with extensive winter stubble, presumably because overwinter survival is relatively high. In a study in France, autumn sown fields were avoided by Skylarks in winter, and a steep depletion in seed abundance was observed in other fields between December and March, with Skylarks showing much stronger flocking behaviour in late winter when seed availability was lowest, suggesting this may be a key period during the winter (Powolny et al. 2018). Note, however, that definitive evidence about Skylark survival rates in the UK and what may have influenced them is not available because the species is rarely ringed and ring-recovery sample sizes are extremely small.

Use of pesticides and associated declines in weed populations and weed-seed abundance have been suggested as another factor in the decline of Skylarks (Wilson 2001). Wilson et al. (1997) found higher densities of Skylarks in organic systems. Chamberlain & Crick (1999) suggest that the use of toxic pesticides mediated through effects on food supplies may be responsible for declines in invertebrate food, due to non-target insects being killed by insecticide and insect food-plants being killed by herbicide. However, since this would in theory affect breeding success, it doesn't seem to have been a problem. Donald et al. (2001) state that, although recent agricultural changes have affected diet and possibly body condition of nestlings, these effects are unlikely to have been an important factor in recent population declines. There may also be implications for overwinter survival, as herbicides reduce weeds, and hence seeds for the winter, making stubbles and uncropped land less valuable as a food resource. However, the increases in pesticide use have happened at the same time as the switch to autumn sowing, so is hard to detect this as a specific effect.

There is some evidence to suggest that high densities of raptors may reduce the abundance of local Skylark populations (Amar et al. 2008b). Chamberlain & Crick (1999) state that recovery of Sparrowhawk numbers has been most evident in the most intensively farmed areas, and that this is correlated with the declines in Skylark numbers across habitats and regions. However, this apparent link cannot be taken as evidence of a causal relationship as there have been many other broad-scale changes in the countryside that are at least as well correlated with Skylark changes. They state that it is doubtful whether predation alone could account for the decreases in Skylark numbers.

Information about conservation actions

Skylark is among the most well-studied farmland species, and the decline is believed to have been caused by agricultural intensification, in particular the change from spring to autumn sowing of crops, which reduces the number of breeding attempts and also the availability of stubbles during the winter. Actions or policies which provide or encourage a mosaic habitat including some spring sown crops and/or some overwinter stubble would therefore benefit Skylarks. If overwinter survival is a significant driver of the declines, actions which provide overwinter food may also help (e.g. set-aside or cover crops).

A substantial amount of work has been undertaken to research options which enable the autumn sowing of crops whilst still enabling Skylarks to raise more than one brood. In particular, these have focused on the provision of 'Skylark plots' (small gaps deliberately left within crops) (Schmidt et al. 2017; Donald & Morris 2005), which are now an option in agri-environment schemes. Plots can be created either at the time of sowing (by turning off the seed drill) or at a later date (by spraying herbicide). The former is a better option for Skylark, as the plots have greater vegetation cover and higher invertebrate abundance, and should be preferred. If plots are created by spraying this should be done no later than December (Dillon et al. 2009).

The provision of grass buffer strips around fields with cereal crops is another agri-environment option which may benefit Skylarks: a study in Sweden found more beetles and spiders in fields with buffer strips and also more Skylarks, but suggested that they may need to be implemented at a landscape scale to be most effective (Josefsson et al. 2013).

Where Skylarks are not nesting in cereal crops, delaying mowing or reducing the number of cuts on silage fields, and reducing stock densities could help improve breeding productivity (Donald et al. 2002).

Policies which reduce the use of pesticides may also benefit Skylarks in the UK: A study modelling population trends predicted that declines would occur or would be worsened in all scenarios including the use of insecticides (Topping et al. 2005).

Publications (1)

The risk of extinction for birds in Great Britain

Author: Stanbury, A., Brown, A., Eaton, M., Aebischer, N., Gillings, S., Hearn, R., Noble, D., Stroud, D. & Gregory, R.

Published: 2017

The UK has lost seven species of breeding birds in the last 200 years. Conservation efforts to prevent this from happening to other species, both in the UK and around the world, are guided by species’ priorities lists, which are often informed by data on range, population size and the degree of decline or increase in numbers. These are the sorts of data that BTO collects through its core surveys.

01.09.17

Papers