Tree Pipit

Introduction

A summer visitor to the forests of the UK, the Tree Pipit is probably best known for its parachuting, lilting song-flight.

Tree Pipits arrive in the UK from their wintering grounds during April. They are only rarely found on the island of Ireland, and only on passage. The species is very much a bird of forest edge and open clearings with isolated trees, from which the males launch themselves into their impressive displays, flying high into the air before parachuting earthbound whilst all the time singing their beautiful song. The UK population fell sharply at the end of the 20th century and the species is on the Red List.

Tree Pipits differ from other pipits in having a short hind claw that may reflect its arboreal habits, with most other pipits being birds of grassland. Ringing data show the long-distance migratory habits of Tree Pipits, with birds reported from as far north as Iceland and a far south as Mauritania.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

ID Videos

This section features BTO training videos headlining this species, or featuring it as a potential confusion species.

Meadow Pipit, Tree Pipit & Skylark

Songs and Calls

Song:

Call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

Tree Pipits occur in greatest abundance in Wales, northern England and Scotland, and thus the marked CBC decline between the first two atlas periods may reflect the range contraction that occurred then in central and southeastern England (Gibbons et al. 1993). BBS data for the species have shown a further severe decrease in England since 1995 and moderate decrease in Wales, although these losses has been offset by moderate increases in Scotland. Recent atlas data show further losses of range, especially in eastern England (Balmer et al. 2013). There has been a decline across Europe since 1980 (PECBMS: PECBMS 2020a>). The species was moved from the green to the amber list of UK Birds of Conservation Concern in 2002, and in 2009 to red, on the strength of its UK population decline (Eaton et al. 2009). It is among a suite of species that winter in the humid zone of West Africa and correspondingly are showing the strongest population declines among our migrant species (Ockendon et al. 2012, 2014). The number of fledglings per breeding attempt increased in the 1970s and 1980s but have since fallen again. Laying dates have shifted earlier by approximately one week.

Distribution

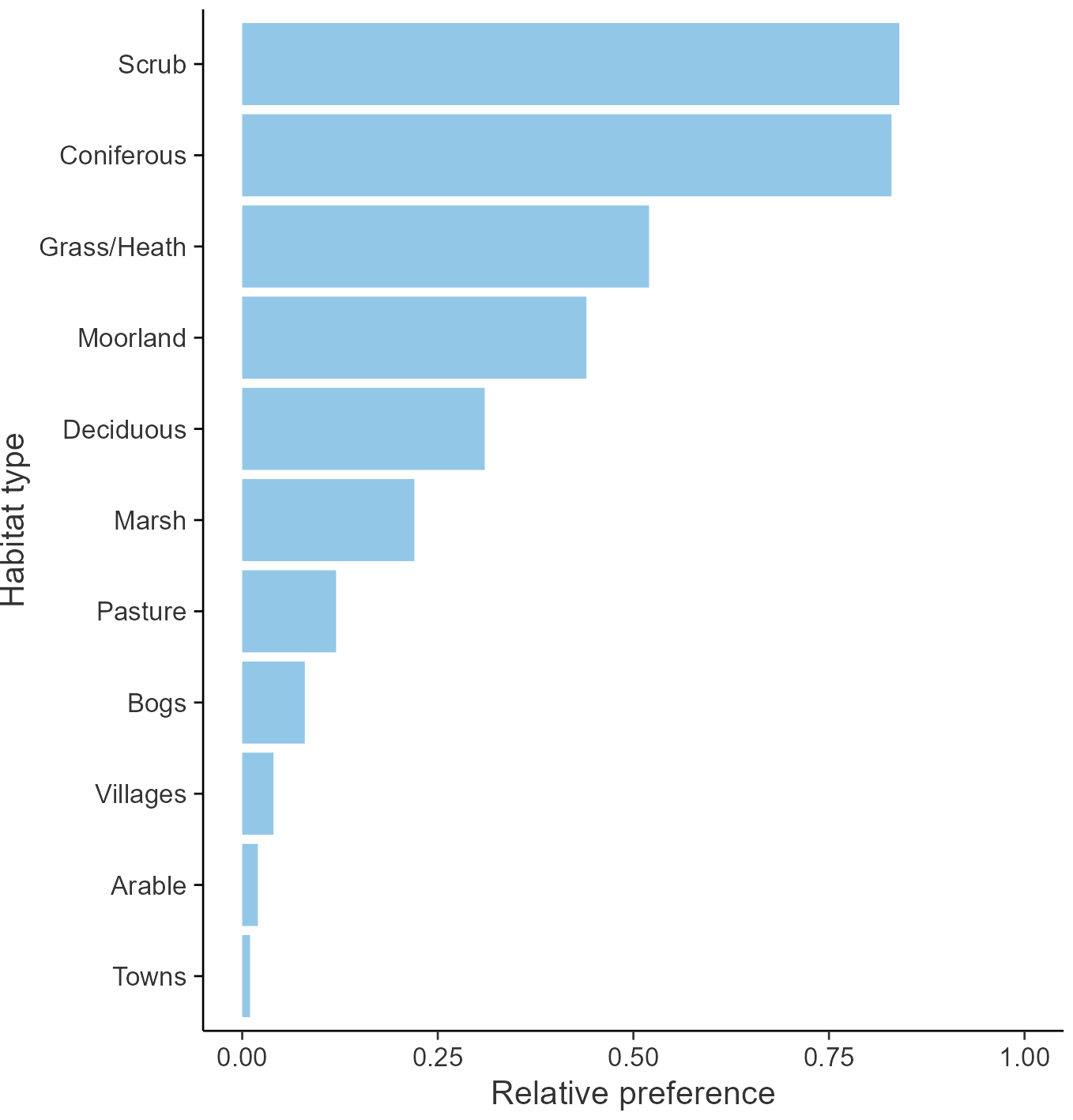

Tree Pipits are summer visitors to wooded and scrub habitats in Britain, occupying areas with prominent song-posts coupled with a sparse field and shrub layer. Such conditions are provided by heavily grazed woods in upland areas, early and clear-fell stages of conifer plantations and lowland heaths and scrubby downland. Tree Pipit distribution is biased towards the west and north, although there are significant populations on southern heaths and in association with forest plantations in East Anglia. They are rare breeders in Ireland.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

The British breeding range of the Tree Pipit is now 29% smaller than is was in 1968–72. Losses have spread from central England in to southeast and northern England and the Scottish Central Belt. In core upland breeding areas abundance has also declined, although there are notable increases in eastern Scotland.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

Seasonality

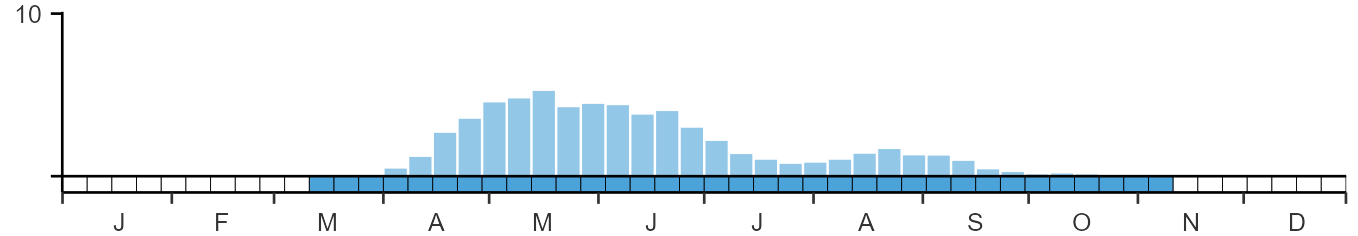

Tree Pipit is a localised summer visitor, arriving through April when it is easily detected by its song; a scarce and under-recorded passage migrant in autumn during August and September.

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

Habitats

Breeding season habitats

Relative frequency by habitat

The graph shows the habitats occupied in the breeding season, with the most utilised habitats shown at the top. Bars of similar size indicate the species is equally likely to be recorded in those habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Incubation

Fledging

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

lifespan

Survival of adults

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Passeriformes

- Family: Motacillidae

- Scientific name: Anthus trivialis

- Authority: Linnaeus, 1758

- BTO 2-letter code: TP

- BTO 5-letter code: TREPI

- Euring code number: 10090

Alternate species names

- Catalan: piula dels arbres

- Czech: linduška lesní

- Danish: Skovpiber

- Dutch: Boompieper

- Estonian: metskiur

- Finnish: metsäkirvinen

- French: Pipit des arbres

- Gaelic: Riabhag-choille

- German: Baumpieper

- Hungarian: erdei pityer

- Icelandic: Trjátittlingur

- Irish: Riabhóg Choille

- Italian: Prispolone

- Latvian: koku cipste

- Lithuanian: miškinis kalviukas

- Norwegian: Trepiplerke

- Polish: swiergotek drzewny

- Portuguese: petinha-das-árvores

- Slovak: labtuška hôrna

- Slovenian: drevesna cipa

- Spanish: Bisbita arbóreo

- Swedish: trädpiplärka

- Welsh: Corhedydd y Coed

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

The availability of suitably structured habitat is important and lack of this may have contributed to the decline, possibly through a decrease in nest survival, although evidence for this is based largely on one site, and analysis of data from six other areas concluded that changes in woodland structure were unlikely to be the main driver of population change. This species being a long-distance migrant, problems on its wintering grounds should not be ruled out.

Further information on causes of change

A detailed, eight-year study in Thetford Forest conducted by Burton (2009) provides good evidence that there was a significant decrease in daily nest survival during the chick stage and that overall nesting success was lowest in clearfells and recently planted stands. Overall nesting success appeared to be determined at the habitat scale, and Burton suggested that this may have been because the broad differences in cover between habitats affected the likelihood of nest predation (the main cause of nest failure). Charman et al. (2009) also found that Tree Pipits have high failure rates at the chick stage and implicate predation. It should be noted that records from Thetford Forest, in southeast England, probably contribute over half the nest records for this species each year; thus these trends may not be representative of the UK as a whole. Research by Mallord et al. (2016) found no evidence that changes in woodland structure affected populations in six study areas in the west of the UK.

This species prefers open ground within woodlands and upland grazed woods lacking understorey, and also occupies clearfells, restocks, new plantations, heaths and commons where trees provide songposts (Fuller 1995, Burton 2007, Charman et al. 2009). The species' decline has been greatest in lowland England, particularly in the wider countryside in woodland and common land (Gibbons et al. 1993) and, accordingly, several authors have proposed that the population decline may be linked to the changing forest structure as new plantations mature, and the reduced management of lowland woods (Fuller et al. 2005, Amar et al. 2006, Charman et al. 2009). Data provided by the Repeat Woodland Bird Survey (RWBS) gives reliable evidence that sub-canopy vegetation increased markedly in almost all regions covered between the 1980s and the early 2000s and analyses found that declines of Tree Pipit occurred in woods with higher maximum tree height and increased foliage (Amar et al. 2006, Smart et al. 2007). Fuller & Moreton (1987) and Burton (2007) provide evidence, respectively, for associations with young coppice and, within coniferous plantations, for young restocks, and a disassociation with closed-canopy woodlands. Amar et al. (2006) state that the lack of new plantations and restocks in southern Britain may have contributed to the decline of this species, although specific analyses providing evidence for this were lacking. They also found that Tree Pipit declined more in sites with more tracks, suggesting disturbance can be an issue (Amar et al. 2006, Smart et al. 2007). Burgess et al. (2015) agree that declining availability of young coniferous woodland contributed to Tree Pipit population decline in England. Targeted management, such as the provision of large blocks of habitat and the retention of mature trees for use as songposts, was found to be beneficial (Burton 2007).

In upland habitats, Fuller et al. (2006) provided evidence showing that both overgrazing and agricultural abandonment of marginal habitats may have detrimental effects on Tree Pipits.

Hewson et al. (2007) analysed the Repeat Woodland Bird Survey and BBS/CBC data and found declines in all of the seven long-distance migrant species considered, including Tree Pipit. Thus, although specific evidence relating to factors operating on the wintering grounds is lacking, these cannot be ruled out as causes of population decline.

Information about conservation actions

The strong decline which occurred in the 1990s is possibly linked to changes in woodland structure, although the evidence for this is contradictory (see Causes of Change section, above). Tree Pipits prefer young coppice or restocks and hence rotational management over large forest areas may be needed to ensure that optimal habitat continues to be available on an ongoing basis. Targeted management, such as the provision of large blocks of habitat and the retention of mature trees for use as song posts, was found to be beneficial in Thetford Forest in East Anglia, with the retention of trees enabling the species to use newly cleared areas immediately rather than waiting a few years until new trees were tall enough to be used as song posts (Burton 2007).

There is also evidence that disturbance can be an issue (Amar et al. 2006; Smart et al. 2007); hence actions to reduce disturbance should also be considered, such as limiting or preventing access to key sites or by focusing recreational activity towards specific areas (e.g. by targeted placement of car parks).

Publications (1)

Evaluating the potential effects of capturing and handling on subsequent observations of a migratory passerine through individual acoustic monitoring

Author: Petrusková, T., Kahounová, H., Pišvejcová, I., Čermáková, A., Brinke, T., Burton, N.H.K. & Petrusek, A.

Published: 2021

This study of Tree Pipits highlights the role that acoustic monitoring can play as a non-intrusive method for the identification of individuals in long-term monitoring studies.

04.05.21

Papers