Whinchat

Introduction

A bird of grassland and meadow, the Whinchat, with its dark face and orange breast has its stronghold in the north and west of the UK.

The Whinchat is a summer visitor to Britain & Ireland, arriving during April but leaving a little earlier than most. Birds can be seen at migration watchpoints during August. It is estimated that Wales holds around a third of the UK breeding population. UK Whinchat numbers have fallen steadily since the late-1990s, likely due to habitat degradation. This species is on the UK Red List.

Whinchats have striking plumage, with a noticeable white eye stripe and orange throat and chest. Males are more strongly coloured than females. The Whinchat spends the winter months in Africa and ringing data reveal several recoveries, with one bird travelling 5,465 km from its Scottish ringing site to Ghana.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

ID Videos

This section features BTO training videos headlining this species, or featuring it as a potential confusion species.

Stonechat, Whinchat and Wheatear

Songs and Calls

Song:

Call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

Whinchats were not monitored by census surveys until the BBS began in 1994. By then, however, Gibbons et al. (1993) had already identified a major range contraction, mainly from lowland England, that was probably at least partly due to more intensive management of farmland (Marchant et al. 1990). Further extinctions have occurred since then among the remaining pockets of lowland breeders in apparently suitable habitat (Balmer et al. 2013) and the species has declined even in upland stronghold areas (Henderson et al. 2014). In the uplands, Whinchat habitat is now somewhat restricted, being sandwiched between intensive agriculture at lower levels and higher land unsuitable for breeding, and limited also by aspect (Calladine & Bray 2012). In a study focused on upland grasslands, a 95% decline was noted between 1968-80 and 1999-2000 (Henderson et al. 2004). BBS data indicate that strong population decline has taken place since 1995, raising alerts for the UK as a whole as well as for England. Nest-record samples are small, but indicate a substantial recent rise in nest losses at the egg stage. In 2012 and 2013, BTO conducted a Wales Chat Survey for Whinchats, Stonechats and Wheatears. The Welsh population was estimated at 2,825 pairs (95% CIs: 1,046-6,027), but could not be easily compared with previous estimates to assess tends (Henderson et al. 2017).

There has been a decline across Europe since 1980 (PECBMS: PECBMS 2020a>). On the strength of its UK decline, Whinchat was moved from the green to the amber list of conservation concern in 2009 and subsequently from amber to the UK red list at the latest review in 2015 (Eaton et al. 2015). It is among a suite of species that winter in the humid zone of West Africa and correspondingly are showing the strongest population declines among our migrant species (Ockendon et al. 2012, 2014).

Distribution

Whinchats are increasingly confined to the marginal uplands of Scotland, northern England, central Wales, Exmoor, Dartmoor and the Isle of Man. Breeding in the lowlands is uncommon in the south with the exception of a few populations in southwest England such as Salisbury Plain. Whinchats are rare breeders In Ireland, with small populations in the Antrim Hills, Kildare bogs, Wicklow Hills and Shannon Callows.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

The breeding range of the Whinchat has been steadily contracting, by 47% in Britain and by 76% in Ireland since 1968–72. Whinchats have been lost from much of central and southeast England and successive atlases have charted further losses in the lowlands and upland fringes.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

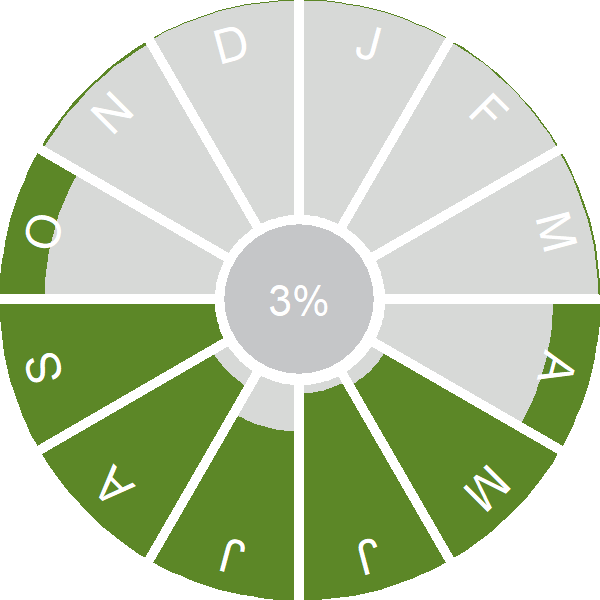

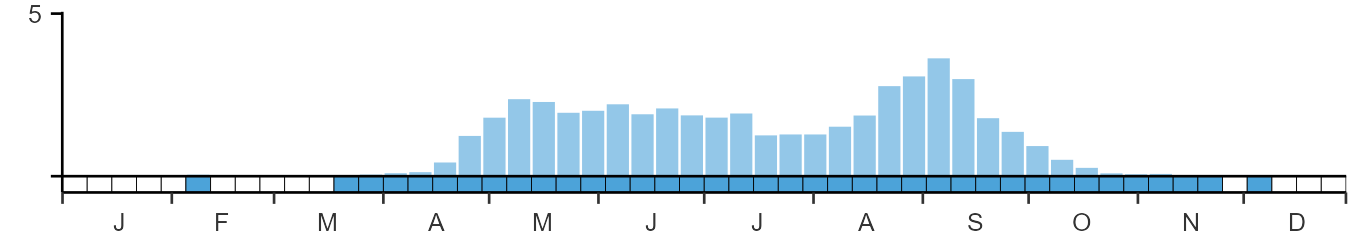

Seasonality

Whinchat is a summer visitor, arriving through April and early May; there is a pronounced autumn passage in August and September.

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

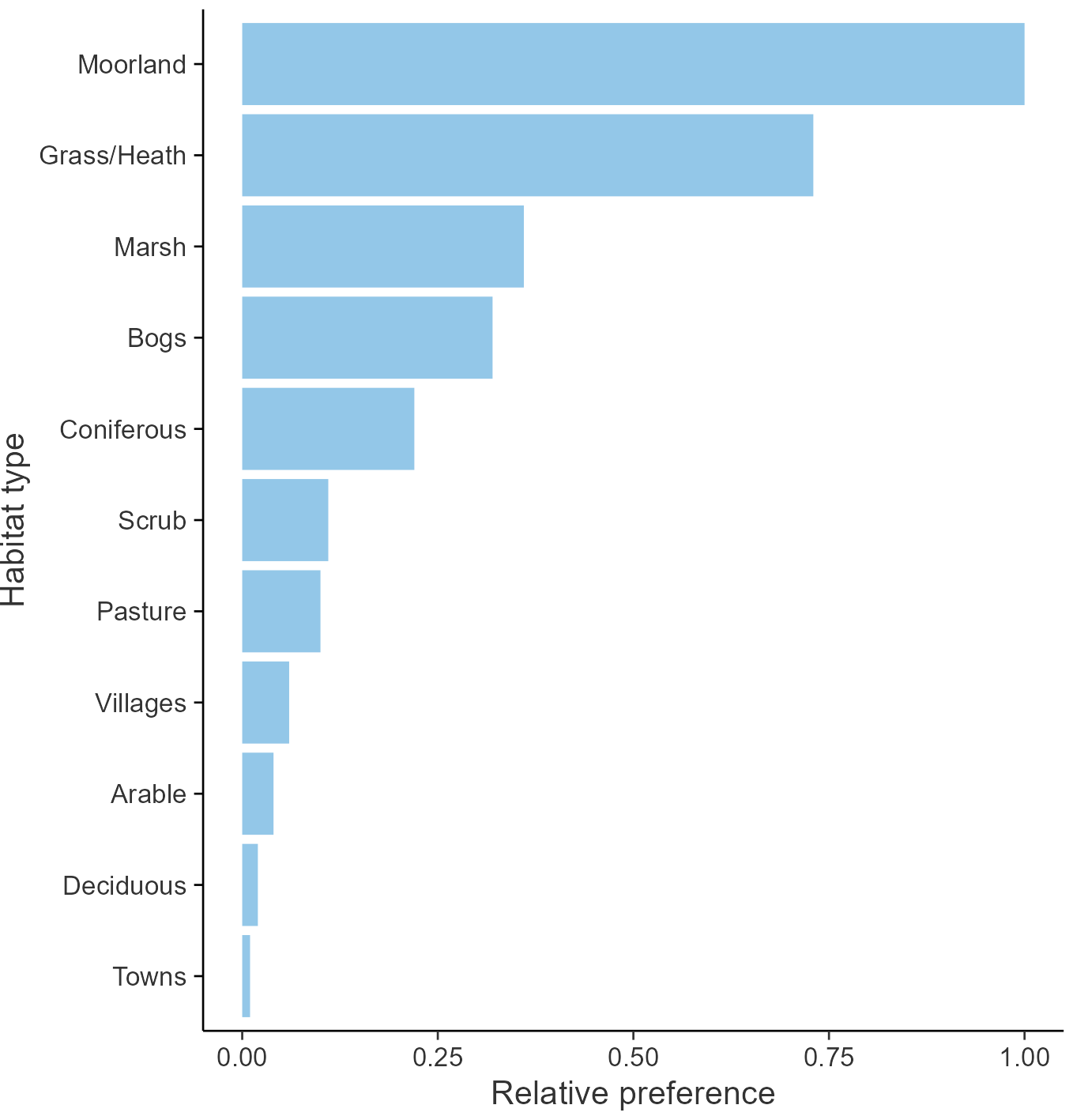

Habitats

Breeding season habitats

Relative frequency by habitat

The graph shows the habitats occupied in the breeding season, with the most utilised habitats shown at the top. Bars of similar size indicate the species is equally likely to be recorded in those habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Incubation

Fledging

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

lifespan

Survival of adults

Survival of juveniles

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Passeriformes

- Family: Muscicapidae

- Scientific name: Saxicola rubetra

- Authority: Linnaeus, 1758

- BTO 2-letter code: WC

- BTO 5-letter code: WHINC

- Euring code number: 11370

Alternate species names

- Catalan: bitxac rogenc

- Czech: brambornícek hnedý

- Danish: Bynkefugl

- Dutch: Paapje

- Estonian: kadakatäks

- Finnish: pensastasku

- French: Tarier des prés

- Gaelic: Gocan-conaisg

- German: Braunkehlchen

- Hungarian: rozsdás csuk

- Icelandic: Vallskvetta

- Irish: Caislín Aitinn

- Italian: Stiaccino

- Latvian: lukstu cakstite

- Lithuanian: paprastoji kiauliuke

- Norwegian: Buskskvett

- Polish: poklaskwa

- Portuguese: cartaxo-nortenho

- Slovak: prhlaviar cervenkastý

- Slovenian: repaljšcica

- Spanish: Tarabilla norteña

- Swedish: buskskvätta

- Welsh: Crec yr Eithin

- English folkname(s): Furzechuck

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

There is good evidence that the long-term historical decline of the Whinchat may be due to changes in management of grassland and semi-managed meadows, with reduction in habitat quality (invertebrates and structure) and scale, both being common features of existing populations. More ringing or colour-ringing data and more nest record data are necessary to fully establish productivity or survival as drivers of population change; however, recent research suggests that productivity is more likely to be the main driver.

Further information on causes of change

Whinchat is a species historically associated with lowland cultivated grassland and semi-natural meadows (Muller et al. 2005, Britschgi et al. 2006, Broyer 2009) as well as upland hill slopes (Calladine & Bray 2012). Specifically Whinchats have been shown to favour areas of long,structurally diverse tussock rich grassland, with a high density of tussocks and an abundance of perches to forage from (Border et al. 2016). Its historical decline in the lowlands has been linked to losses of suitable habitat and changes in management of grassland (Holloway 1996). Early mowing of grassland habitats generally causes direct losses of nests and even mortality of incubating females and, indirectly, makes the birds more conspicuous to predators (Gruebler et al. 2008). As the predator avoidance strategy of recently fledged young is to sit still and hide, they remain vulnerable to mowing for up to 14 days after they have left the nest, and mowing has been identified as the most important threat to this species by one European study which compared it with other factors affecting breeding productivity including predation and weather (Tome et al. 2020). Grassland intensification reduces invertebrate availability, through direct removal with cut grass, and by reducing vegetation diversity due to the application of fertilisers (Britschgi et al. 2006).

An increasing proportion of the population in Europe is now found in the uplands, where agricultural intensification has been less marked (Muller et al. 2005, Archaux 2007, Broyer 2009), although some upland areas may now be at an early stage of intensification (Strebel et al. 2015). In the UK, Whinchats are now largely considered an 'upland' species because lowland populations are now rare and confined to expansive protected habitats, such as Salisbury Plain (Henderson et al. 2014). Upland margins have become refuges for species that have declined in farmland (Fuller et al. 2006), with upland grassland and moorland now supporting the breeding population of Whinchats (Stillman & Brown 1994, Gillings et al. 2000). However, even here populations have declined in the last 20 years (Henderson et al. 2014). Calladine & Bray (2012) point out that such Whinchat habitat in the uplands is becoming more limited than may at first appear. Certainly, upland margins are vulnerable to long-term changes in grazing pressure, which has been increasing since the mid 1970s (Fuller & Gough 1999, Fuller et al. 2006).

Demographic data are insufficient to investigate whether trends in breeding productivity or survival have influenced population size in the UK, but one intensive study on Salisbury Plain found that while adult return rates were good, first year return rates were low, and did not appear to be sufficient to maintain the observed population trend, perhaps suggesting high natal dispersal even though this population appears to be isolated (Border et al. 2017); At the same time, nest losses to predation were high (Taylor 2015). Sufficient data are available to carry out modelling using survival estimates and Whinchat trends across Europe (Fay et al. 2020) , which concluded that adult mortality does not explain the trends, and that low productivity is most likely to be the main driver of European trends. Meanwhile, a study over three winters at one site in Nigeria show high survival rates of marked Whinchats within and between winters, suggesting that mortality at this site occurs primarily outside the wintering period and probably during migration (Blackburn & Cresswell 2016a, 2016b). Another study found that British breeding Whinchats winter over a wide area in Africa, suggesting that winter factors are unlikely to have driven UK declines unless they operate over a very broad scale (Burgess et al. 2020).

Information about conservation actions

There is good evidence that the decline of this species is related to more intensive habitat management. The conservation and re-creation of semi-natural habitat to maintain and increase the diversity (of both invertebrates and habitat structure) is likely to benefit Whinchats, in particular in upland areas which have become important for this species and which are also now subject to increasing agricultural intensification. These upland margins are vulnerable to long-term changes in grazing pressure.

Where Whinchats are nesting in pasture, the most important conservation action is delaying mowing. Early mowing of grassland causes direct loss of nests and also makes birds more conspicuous and therefore more vulnerable to predators ( Gruebler et al. 2012; Strebel et al. 2015). Furthermore, there are concerns that delaying mowing until after almost all nests have fledged may not be sufficient, as the predator avoidance strategy of recently fledged young is to sit still and hide meaning that they remain vulnerable to mowing for ten to 14 days after they have left the nest (Tome & Denac 2012; Tome et al. 2020). Policies to enable and encourage delayed mowing should therefore ensure that mowing does not take place until the end of this additional period of vulnerability.

As well as early mowing, agricultural intensification also leads to decreases in the availability of invertebrates in grassland habitats, in particular important nestling food (Britschgi et al. 2006). Hence actions and policies such as reducing the application of fertilisers and insecticides, and maintaining or creating a suitable habitat mosaic for Whinchats are also important.

On British moorland, Whinchats are most visible in tall vegetation, such as bracken (Allen 1995) and scrub, but mainly where there is grassy ground cover (Pearce-Higgins & Grant 2006), and vegetation height is more complex instead of uniform (Buchanan et al. 2017). In all its breeding habitats, lowland and upland, common features are perches (tall flower stems, bracken, light scrub, small trees) admixed with structurally varied, insect rich, grassland (to provide food and tussocks for nest sites). Vegetation that does not allow access to ground invertebrates is too dense to suit this species (Thompson et al. 1995), and grazing may help provide suitable mosaic conditions (Murray et al. 2016, Douglas et al. 2017). On the other hand, grazing can reduce tussock density for nest sites and reduce breeding success by exposing nests to increased risk from predation (Taylor 2015).

Publications (5)

The benefits of protected areas for bird population trends may depend on their condition

Author: Brighton, C.H., Massimino, D., Boersch-Supan, P., Barnes, A.E., Martay, B., Bowler, D.E., Hoskins, H.M.J. & Pearce-Higgins, J.W.

Published: 2024

BTO-led research highlights the importance of the quality of protected areas in their effectiveness.

28.03.24

Papers

Upward elevational shift by breeding Whinchat Saxicola rubetra in response to cessation of grazing in upland grassland

Author: Calladine, J. & Jarrett, D.

Published: 2021

This study in the Scottish uplands shows that cessation of grazing which results in more uniform tall ground vegetation leads to Whinchats breeding at higher elevations. Whinchats prefer ground vegetation with a varied structure and these changes result in them heading to higher ground where the environment can prove to be too harsh for them.

28.08.21

Papers

Nest monitoring does not affect nesting success of Whinchats Saxicola rubetra

Author: Border, J.A., Atkinson, L.R., Henderson, I.G., Hartley, I.R.

Published: 2017

A new paper, resulting from a collaborative study between BTO and Lancaster University showed that monitoring nests has no effect on daily survival rates of Whinchat nestlings. To ensure that monitoring efforts do not affect survival rate of nestlings and young birds, it is important to assess their impact. Nest monitoring could potentially lead predators to the nest or cause parents to desert or reduce parental care effort to their nestlings. This paper investigated 39 nests to determine whether monitoring has an adverse effect on daily survival rate in Whinchats at Salisbury Plain, Wiltshire.Nests were either visited only once upon their initial detection, or every two days during the incubation period. The visited nests did not have a lower survival rate than the non-visited nests, suggesting that there are no adverse effects of monitoring on incubation.During the nestling stage, the nests were monitored once a day on three consecutive days, by using a video camera to record the parents’ behaviour. This part of the study found that nest disturbance by setting up monitoring equipment temporarily reduced the feeding behaviour of the parents, but this only added up to 0.52% of total nestling time; a non-significant portion of the total time a nestling spends with its parents. In conclusion, this study found that monitoring Whinchat nests every two to three days has no negative effect on survival rate, and although birds can become slightly disturbed, they will soon resettle into normal behaviour. The authors emphasise that precautions to minimise potential impact on nests should always be taken and that guidelines for nest monitoring should always be adhered to.

30.12.17

Papers

Habitat selection by breeding Whinchats Saxicola rubetra at territory and landscape scales.

Author: Border, J. A., Henderson, I. G., Redhead, J. W. & Hartley, I. R.

Published: 2016

12.12.16

Papers

An experimental evaluation of the effects of geolocator design and attachment method on between-year survival on whinchats Saxicola rubetra

Author: Blackburn, E., Burgess, M., Freeman, B., Risely, A., Izang, A., Ivande, S., Hewson, C. & Cresswell, W.

Published: 2016

24.02.16

Papers