Wood Warbler

Introduction

Very much a bird of western Oak woods, the Wood Warbler, with its yellow throat and silvery-white underparts is the least common of the UK's breeding leaf warblers.

The Wood Warbler visits Britain & Ireland from April to September and is very much a bird of western Britain, from Dartmoor to north-west Scotland, reflecting its Atlantic Oak breeding habitat. Small numbers of breeding birds can be found elsewhere in the UK and Ireland but they are the exception. The Wood Warbler's song, likened to a spinning coin, is a good way to locate a male in spring.

The Wood Warbler has been on the UK Red List since 2009 as a bird in need of conservation action due to a decline in its numbers. It spends the winter months south of the Sahara.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

Songs and Calls

Song:

Call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

Wood Warblers, which have a westerly distribution in Britain, were monitored relatively poorly until BBS began. Little change was evident at the few CBC plots on which the species occurred (Marchant et al. 1990). The species' breeding range varied little between the first two atlas periods (Gibbons et al. 1993), but has subsequently withdrawn from large areas of lowland England (Balmer et al. 2013). BBS shows a rapid and significant decline since 1995, and accordingly the species was moved from the green to the amber list in 2002; the continued decline warranted a further shift to the red list in 2009. With declines evident across northern and western Europe, this previously 'secure' species is now provisionally categorised as 'declining' (BirdLife International 2004). There has been a decline across Europe since 1980 (PECBMS: PECBMS 2020a>).

Distribution

Breeding Wood Warblers are mainly found in western Britain where they favour mature closed-canopy woodland, particularly Sessile Oak and Silver Birch. The highest densities are associated with wooded uplands, mainly in southwest England, Wales and the Marches, the Peak District, the northern Pennines and Cumbria. In Scotland the main strongholds are in Galloway and in the western Highlands from Argyll to Inverness-shire.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

Between 1968–72 and 1988–91 Wood Warblers were lost from many areas of southern and central England, although the overall range size remained almost unchanged. Subsequently there has been a 37% range contraction since the 1988–91 Breeding Atlas. The losses are particularly evident on lower ground in the south and east, and around the margins of the core areas.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

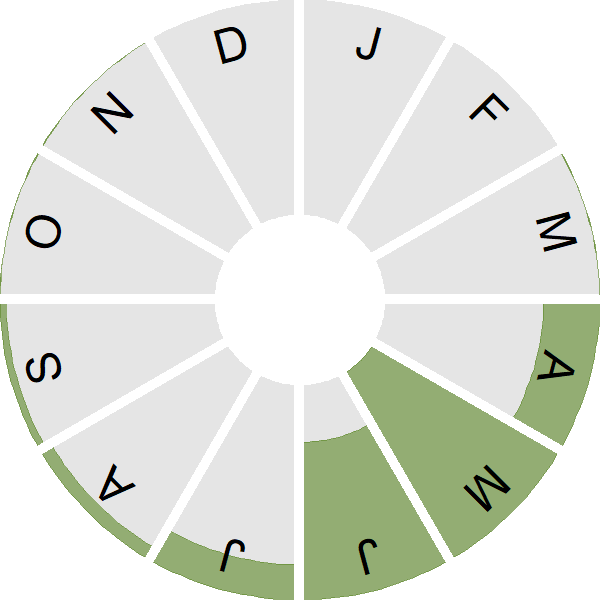

Seasonality

Wood Warbler is a scarce summer visitor, arriving from mid April and seen rarely during autumn migration in August and September.

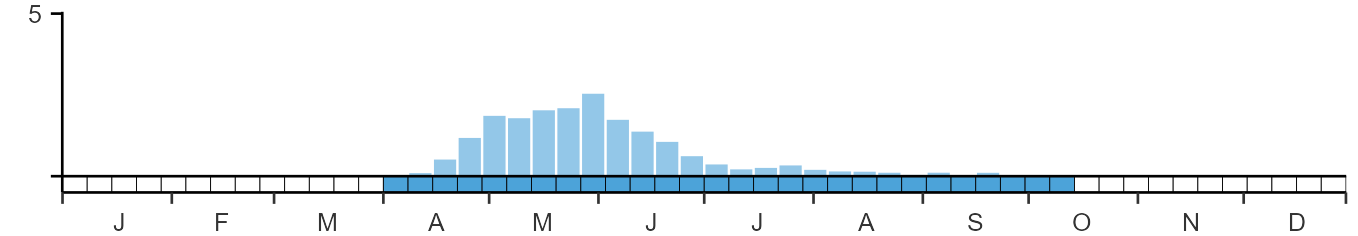

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Incubation

Fledging

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

lifespan

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Passeriformes

- Family: Phylloscopidae

- Scientific name: Phylloscopus sibilatrix

- Authority: Bechstein, 1793

- BTO 2-letter code: WO

- BTO 5-letter code: WOOWA

- Euring code number: 13080

Alternate species names

- Catalan: mosquiter xiulaire

- Czech: budnícek lesní

- Danish: Skovsanger

- Dutch: Fluiter

- Estonian: mets-lehelind

- Finnish: sirittäjä

- French: Pouillot siffleur

- Gaelic: Ceileiriche-coille

- German: Waldlaubsänger

- Hungarian: sisego füzike

- Icelandic: Grænsöngvari

- Irish: Ceolaire Coille

- Italian: Luì verde

- Latvian: svirlitis

- Lithuanian: žalioji pecialinda

- Norwegian: Bøksanger

- Polish: swistunka lesna

- Portuguese: felosa-assobiadeira

- Slovak: kolibiarik sykavý

- Slovenian: grmovšcica

- Spanish: Mosquitero silbador

- Swedish: grönsångare

- Welsh: Telor Coed

- English folkname(s): Wood/Yellow Wren

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

There is little evidence explaining either the demographic or ecological drivers of the decline in this species and the causes are largely unknown.

Further information on causes of change

Nest failures now seem more likely to occur at the chick stage, although nest record samples are small. There has been no real change in the number of fledglings per breeding attempt, with a very shallow increase in productivity until the mid-1990s being followed by a similar decrease.

Bibby (1989) postulated that soils, climate, competition or predator numbers have probably had an effect on Wood Warbler numbers but provided no evidence in support. Smart et al. (2007) state that the loss of oak trees, the decrease in canopy cover, and the large increases in understorey cover could have been particularly detrimental for Wood Warbler, but again, direct evidence to validate this is largely lacking. Mallord et al. (2016) found no evidence that changes in woodland structure affected populations in their study areas in the west of the UK. Bellamy et al. (2017) found that nest predation was slightly lower in areas with more medium-height vegetation (e.g. brambles) but concluded that the effect of vegetation management would be small, apart from in extreme cases where very low cover exists. Smart et al. (2007) and Amar et al. (2006) did find that Wood Warblers have tended to decrease more in woods with fewer dead limbs on trees and at sites surrounded by more woodland, which suggests that changes in dead wood could be important or that dead limbs could be a surrogate for other changes in habitat, although Smart et al. (2007) found an overall increase in the amount of dead wood, which should have been beneficial for this species. In another Welsh study, Mallord et al. (2012b) found that Wood Warblers were associated with a number of structural features of the study woods, which could relate to their past management; they suggest that management should aim to restore habitat quality through introducing a moderate grazing regime.

Studies in Poland, where an average of over 70% of nests were lost and predators were responsible for over 80% of the losses, have reported that varying predation rates were a main factor responsible for variation in production between years and habitats (Wesolowski 1985). Wesolowski & Maziarz (2009) provided further evidence relating to this, finding that both Wood Warbler numbers and ratios of their change were significantly negatively correlated with rodent numbers. However, predators in Poland were mainly medium-sized carnivores (Maziarz et al. 2019) hence the observed correlation with rodent numbers may relate to changes in predator behaviour when rodent numbers were high.

Note that the findings from Poland cannot necessarily be linked to UK trends as different predators have been observed here. In Wales, nest predators during 2009-11 were mainly avian and rates of predation did not appear to have changed since 1982-84 (Mallord et al. 2012a). Subsequent analysis, looking at nests from the New Forest (2011-13) and Dartmoor (2012-13) alongside those from Wales also identified avian predators as the most important, but also found that higher predation rates had occurred in the New Forest where the predators were more diverse (Bellamy et al. 2017).

Mismatch between timing of breeding and the seasonal peaks of caterpillar abundance is potentially not a serious problem for Wood Warblers, because of their ability to feed their young successfully on flying insects and spiders (Mallord et al. 2017).

This species is a long-distance migrant and therefore changes outside the breeding grounds cannot be ruled out. A wintering study identified some possible resilience to forest loss as wintering birds can still use degraded habitats, but only where a substantial number of trees remain (Mallord et al. 2018). Data suggest that loss of tree cover in the wintering range may not be a key driver of the historical declines (Buchanan et al. 2019). However continued loss of trees in the future is likely to affect Wood Warblers in winter (Mallord et al. 2018).

Information about conservation actions

Habitat management to provide and maintain good quality woodland is likely to be important to conserve this declining species, with Mallord et al. (2012b) suggesting that habitat should be restored by implementing a moderate grazing regime. Wood Warblers require large areas of broad-leaved woodland and territories are associated with habitat variables including higher canopy height and intermediate levels of canopy cover, slope steepness and field level vegetation (Mallord et al. 2012b). Grass and sedge tussocks were important for nest survival in a study in Switzerland, which suggested stands with little or no shrub layer should be preferred to encourage ground level vegetation (Grendelmeier et al. 2015), although a UK study found predation rates decreased slightly when there was more medium height vegetation (Bellamy et al. 2018). Nests are located on steeper slopes (Bellamy et al. 2018); hence broad-leaved woodlands on slopes should be prioritised for conservation (Huber et al. 2017).

Publications (1)

Loop-migration and non-breeding locations of British breeding Wood Warbler Phylloscopus sibilatrix

Author: Burgess, M., Castello, J., Davis, T. & Hewson, C.

Published: 2022

New research has revealed the wintering grounds and migration stopovers of British-breeding Wood Warbler, a declining species on the UK Birds of Conservation Concern Red List.

16.11.22

Papers