Yellow Wagtail

Introduction

The Yellow Wagtail is a summer visitor, breeding primarily in southern and eastern Britain.

This is a strongly migratory species, wintering in trans-Saharan Africa and returning from early April to breed in grassy habitats, particularly in proximity to cattle. There has been a major decline in numbers since the 1970s, albeit with more stability over the last decade. The decline appears strongly linked to agricultural intensification.

Along with the decline in numbers, the Yellow Wagtail has also undergone range contraction. Most of our breeding birds are now found in central and northern England. It is extinct as a breeding bird on the island of Ireland, where is now only found while on passage.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

ID Videos

This section features BTO training videos headlining this species, or featuring it as a potential confusion species.

Yellow-coloured wagtails

Songs and Calls

Song:

Call:

Flight call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

Britain holds almost the entire world population of the distinctive race flavissima, so population changes in the UK are of global conservation significance. Yellow Wagtails have been in rapid decline since the early 1980s, according to CBC/BBS and especially WBS/WBBS and, after a shift from the green to the amber list in 2002, the species was moved to the red list in 2009 (Eaton et al. 2009). Gibbons et al. (1993) identified a range contraction towards a core area in central England, concurrent with the early years of decline. Further range contraction has occurred extensively since then, especially in the west and south and in parts of East Anglia (Balmer et al. 2013). The European trend, which comprises several races of the species, has shown a decline since 1980 (PECBMS: PECBMS 2020a>).

Distribution

The majority of the UK's Yellow Wagtails now breed in England, with none breeding in Ireland and only a few squares occupied in Wales and Scotland during 2008–11. Densities are highest in East Yorkshire, Lincolnshire, the Fens, Broadland and the Essex and Kent coastal marshes.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

Breeding Yellow Wagtails have been lost from many parts of southern England, northwest England, Wales, the Scottish Borders and the Central Belt. In the remaining range relative abundance has decreased with only East Lincolnshire and East Yorkshire showing signs of growth.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

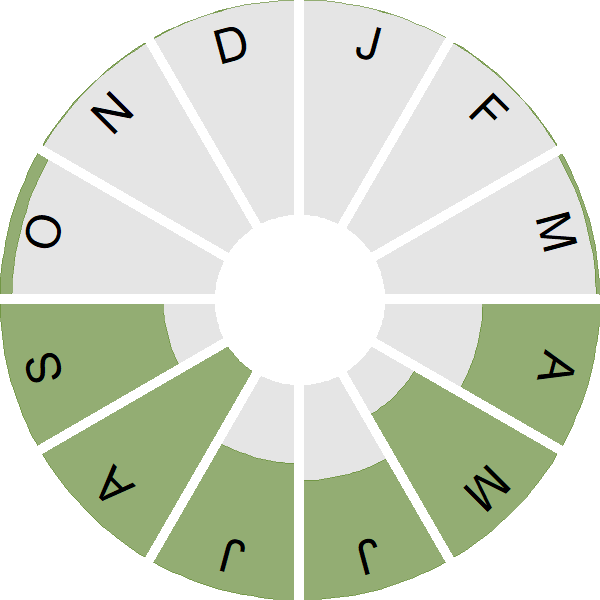

Seasonality

Yellow Wagtail is a localised summer migrant, arriving in April; can be seen more widely during autumn passage, often at wetlands, but most have departed by October.

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

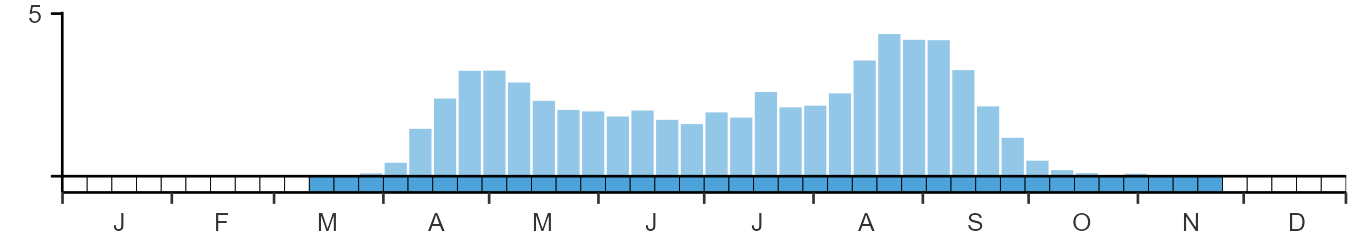

Habitats

Breeding season habitats

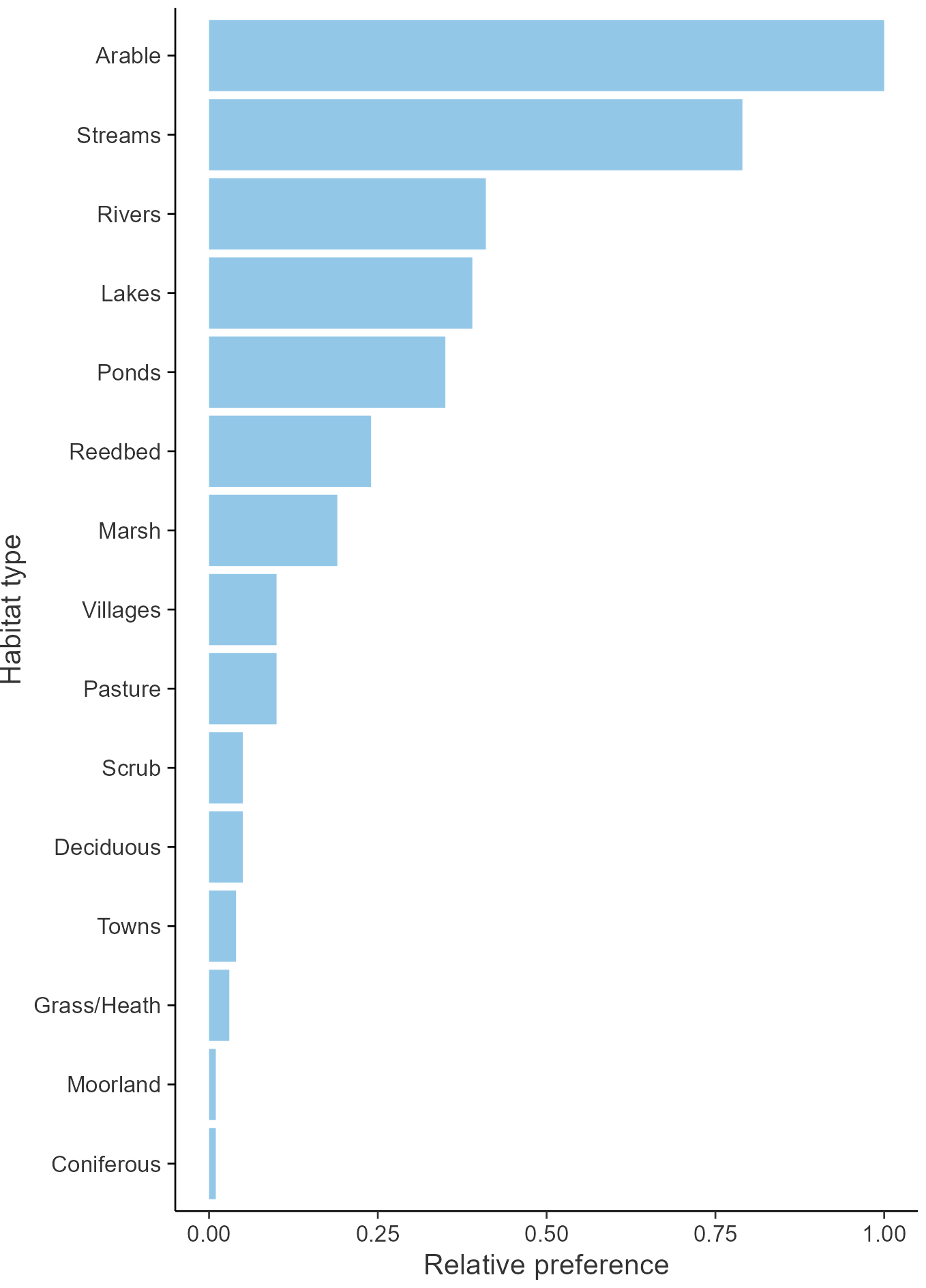

Relative frequency by habitat

The graph shows the habitats occupied in the breeding season, with the most utilised habitats shown at the top. Bars of similar size indicate the species is equally likely to be recorded in those habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Incubation

Fledging

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

lifespan

Survival of adults

Survival of juveniles

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Passeriformes

- Family: Motacillidae

- Scientific name: Motacilla flava

- Authority: Linnaeus, 1758

- BTO 2-letter code: YW

- BTO 5-letter code: YELWA

- Euring code number: 10170

Alternate species names

- Catalan: cuereta groga

- Czech: konipas lucní

- Danish: Gul Vipstjert

- Dutch: Gele Kwikstaart

- Estonian: hänilane

- Finnish: keltavästäräkki

- French: Bergeronnette printanière

- Gaelic: Breacan-buidhe

- German: Schafstelze

- Hungarian: sárga billegeto

- Icelandic: Gulerla

- Irish: Glasóg Bhuí

- Italian: Cutrettola

- Latvian: dzeltena cielava

- Lithuanian: geltonoji kiele

- Norwegian: Gulerle

- Polish: pliszka zólta

- Portuguese: alvéola-amarela

- Slovak: trasochvost žltý

- Slovenian: rumena pastirica

- Spanish: Lavandera boyera

- Swedish: gulärla

- Welsh: Siglen Felen

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

Agricultural intensification is the ultimate cause of population declines. However, the mechanisms underlying the decline remain unclear.

Further information on causes of change

Changes in agricultural practices have been proposed as the main reason for declines via their impact on the quality of foraging and breeding habitats. The magnitude of Yellow Wagtail decline appears to vary between habitats, being strongest in wet grassland and marginal upland areas (Henderson et al. 2004, Wilson & Vickery 2005). Chamberlain & Fuller (2000, 2001) found that there were greater range contractions in regions dominated by pastoral agriculture. The decline in pastoral habitats has been proposed to be due to agricultural intensification, specifically farmland drainage, the conversion of pasture to arable land, changes in grazing and cutting regimes, the loss of insects associated with cattle and changes to grassland ecosystems in marginal upland areas (Gibbons et al. 1993, Chamberlain & Fuller 2000, 2001, Flyckt 1999, Vickery et al. 2001, Nelson et al. 2003, Bradbury & Bradter 2004, Henderson et al. 2004). Such changes are likely to have reduced the quality of grasslands as a nesting and foraging habitat.

Data from eastern England suggest a strong avoidance of grassland and preference for spring-sown crops (Mason & Macdonald 2000), though breeding can also be successful in landscapes dominated by winter cereals (Kirby et al. 2012). A detailed autecological study by Gilroy et al. (2008) provides good evidence that, on arable land, soil penetrability had a significant influence on the abundance of Yellow Wagtails, together with crop type and soil type, as these influenced invertebrate capture rates. There was a strong relationship between Yellow Wagtails and soil penetrability, suggesting a potential causative link between soil degradation and population decline (Gilroy et al. 2008). Breeding-season length may also be limited in cereal-dominated areas, as Yellow Wagtails avoid autumn-sown cereals late in the season (Gilroy et al. 2009, 2010). Predation was also considered and it was found that predation rate was closer nearer to tramlines and field-edges (Morris & Gilroy 2008). It is uncertain how important nest predation in tramlines is as a limiting factor for Yellow Wagtail populations but no studies have reported predation as a major driver of population decline for this species. Work carried out by Benton et al. (2002) showed that, in Scotland, arthropod abundance was significantly related to agricultural change and that this was also linked to measures of farmland bird density. Although Yellow Wagtail does not breed on Scottish farmland, it is an obligate insectivore, so this evidence adds support to the hypothesis that reduced food availability due to agricultural change may have contributed to the declines in this species.

Yellow Wagtails are long-distance migrants, moving to wintering grounds in western Africa south of the Sahara. Factors relating to conditions on the wintering grounds may also play a role (Bradbury & Bradter 2004, Heldbjerg & Fox 2008, Stevens et al. 2010) but evidence for this is lacking.

Information about conservation actions

The decline of the Yellow Wagtail since the 1980s is believed to be driven by agricultural intensification and resultant habitat changes, although the exact mechanism behind the decline is unclear and therefore specific evidence-based conservation actions to reverse the decline are limited. However, there is good knowledge about breeding habitat preferences.

The research suggests that changes to cattle farming and associated grassland may have reduced quality and food availability; hence actions which enable low intensity pastoral farming may benefit Yellow Wagtails, including a reduction in the use of fertilisers, herbicides and pesticides to provide more diverse semi-natural grasslands. A detailed study of Yellow Wagtail breeding ecology by Bradbury and Bradter (2004) provided good evidence of the species' breeding requirements on grassland. Territories were associated with a greater proportion of bare earth in the sward, the presence of shallow-edged ponds or wet ditches in the field, and a greater probability of a prolonged winter/spring flood, although the relative importance of these and how they impact on demographic processes was indecipherable.

Where Yellow Wagtails nest in arable fields, providing spring sown crops may help improve breeding productivity by extending the breeding season (Mason & McDonald 2000). Alternatively, providing a mosaic of crops may enable Yellow Wagtails to raise early broods in autumn sown cereal fields but switch to other crops (e.g. potatoes) for later broods (Gilroy et al. 2010).

Publications (1)

Birds of Conservation Concern Wales 4: the population status of birds in Wales

Author: Johnstone, I.G., Hughes, J., Balmer, D.E., Brenchley, A., Facey, R.J., Lindley, P.J., Noble, D.G. & Taylor, R.C.

Published: 2022

The latest review of the conservation status of birds in Wales. The report assessed all 220 bird species which regularly occur in Wales. There are now 60 species of bird on the Red List, with 91 on the Amber List and just 69 - less than a third of the total number of species - on the Green List.

06.12.22

Reports Birds of Conservation Concern