Yellowhammer

Introduction

The male Yellowhammer's bright yellow head shines like a beacon in its favoured hedgerow habitat and contrasts beautifully with its deep chestnut body.

The female Yellowhammer is a more subtle version of the male but no less beautiful. The Yellowhammer is a bird of farmland and is one of the 19 species that make up the UK Farmland Bird Indicator, an annual health check of our farmlands birds. As a group they are beleaguered and the Red-listed Yellowhammer is no exception, with a long-term decline in UK breeding numbers.

The Yellowhammer is widely distributed in both the breeding season and winter. It can be found from the northern tip of Scotland to the most south westerly tip of Cornwall, and in Ireland. However, it is less prevalent in upland areas and in the farthest north-west regions of Scotland and the island of Ireland.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

ID Videos

This section features BTO training videos headlining this species, or featuring it as a potential confusion species.

Farmland buntings

Songs and Calls

Song:

Call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

Yellowhammer abundance began to decline on farmland in the mid 1980s. The BBS map of change in relative density between 1994-96 and 2007-09 indicates that in Britain there was a sharp divide between decrease over that period in the east and south and limited increase in the northwest; the population in Northern Ireland has also declined. Atlas surveys in 2008-11 indicate that range loss in Northern Ireland and western Britain, first noted in 1988-91, has continued strongly (Balmer et al. 2013). Recent BBS data confirms that the earlier trends have continued, with a moderate decrease since 1995 recorded in England and a steep decrease in Wales, contrasting with shallow increase in Scotland. The species, listed as green in 1996, has been red listed since 2002. There has been a decline across Europe since 1980 (PECBMS: PECBMS 2020a>).

Distribution

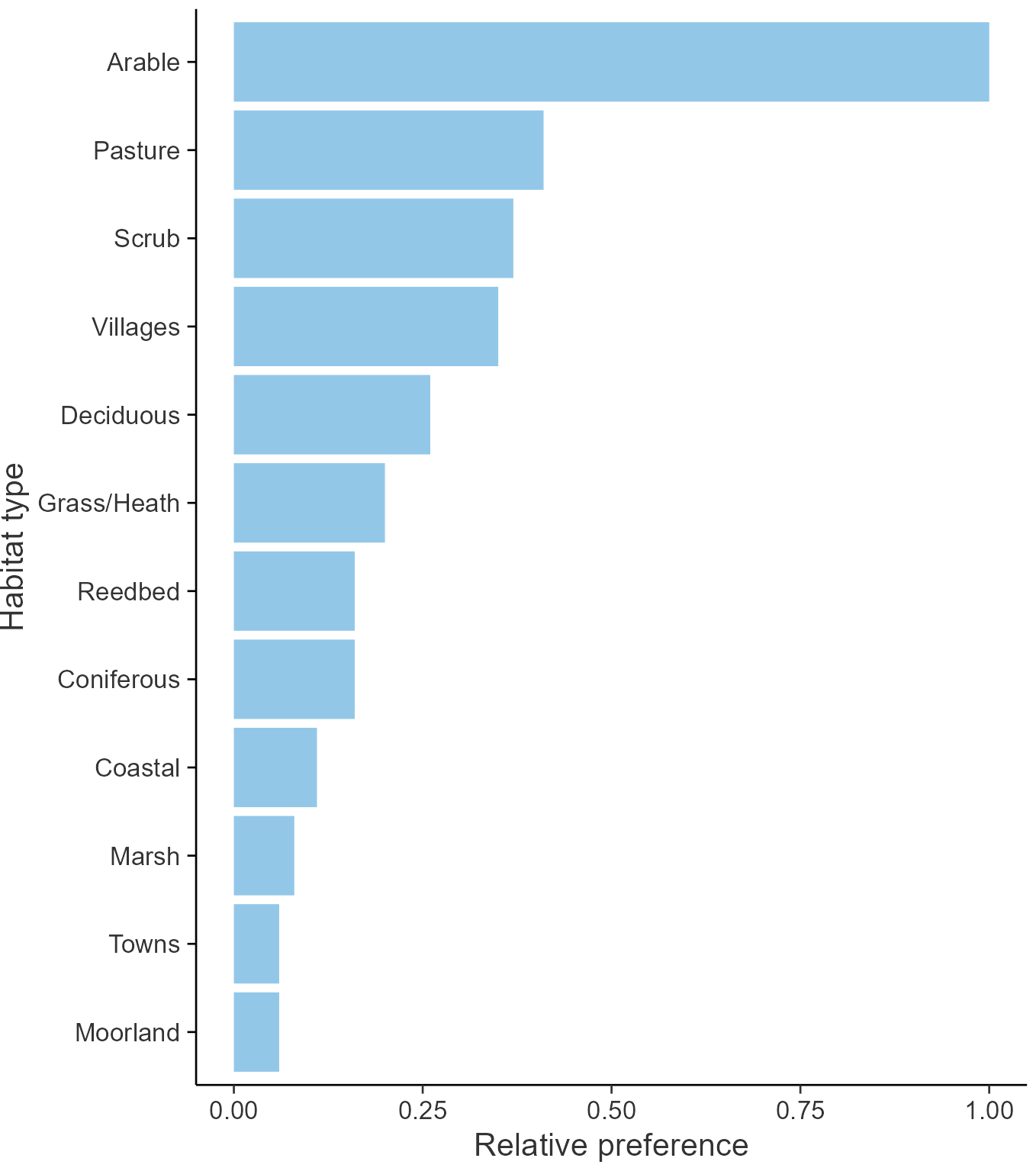

The winter and breeding-season distributions of the largely sedentary Yellowhammer are almost identical, encompassing low-lying areas of mainland Britain and southern and eastern Ireland. They rarely breed in the Outer Hebrides or Northern Isles. With a strong association with arable farmland, densities are generally highest in eastern Britain and are lower in Ireland, even in the southeast.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

Population declines have brought about major range contractions, of 61% in Ireland and 21% in Britain since the 1968–72 Breeding Atlas. In Britain losses have gradually accumulated in the west and in the Pennines. In both Britain and Ireland, atlas data suggest that densities have decreased throughout the remaining range between 1988–91 and 2008–11.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

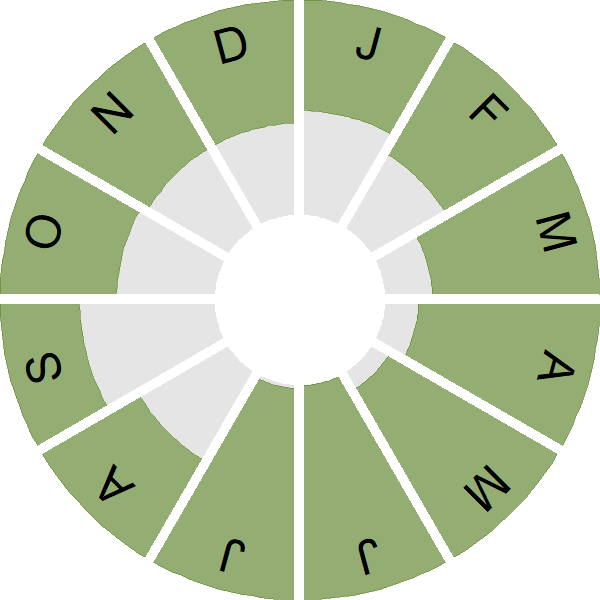

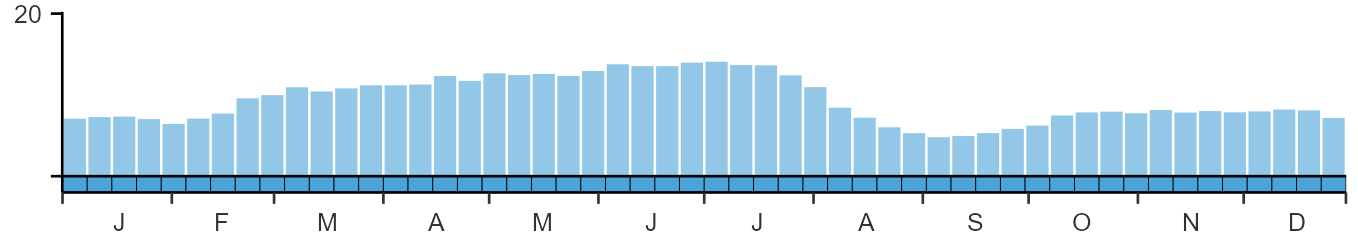

Seasonality

Yellowhammer is widely recorded throughout the year.

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

Habitats

Breeding season habitats

Relative frequency by habitat

The graph shows the habitats occupied in the breeding season, with the most utilised habitats shown at the top. Bars of similar size indicate the species is equally likely to be recorded in those habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Incubation

Fledging

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

lifespan

Survival of adults

Survival of juveniles

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Passeriformes

- Family: Emberizidae

- Scientific name: Emberiza citrinella

- Authority: Linnaeus, 1758

- BTO 2-letter code: Y.

- BTO 5-letter code: YELHA

- Euring code number: 18570

Alternate species names

- Catalan: verderola

- Czech: strnad obecný

- Danish: Gulspurv

- Dutch: Geelgors

- Estonian: talvike

- Finnish: keltasirkku

- French: Bruant jaune

- Gaelic: Buidheag-bhealaidh

- German: Goldammer

- Hungarian: citromsármány

- Icelandic: Gultittlingur

- Irish: Buíóg

- Italian: Zigolo giallo

- Latvian: dzeltena sterste

- Lithuanian: geltonoji starta

- Norwegian: Gulspurv

- Polish: trznadel (zwyczajny)

- Portuguese: escrevedeira-amarela

- Slovak: strnádka obycajná

- Slovenian: rumeni strnad

- Spanish: Escribano cerillo

- Swedish: gulsparv

- Welsh: Bras Melyn

- English folkname(s): Yellow Bunting

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

Declines in annual survival have been proposed as the demographic mechanism for decline, due to winter resource limitation, although ring-recovery data are sparse and so most evidence for this is indirect.

Further information on causes of change

Yellowhammer is unique among farmland birds in that its population was stable until the mid 1980s, followed by a decline, suggesting that it alone was affected by some change that occurred in the 1980s (Siriwardena et al. 1998a). There is some evidence that survival rates decreased during the initial period of decline (Siriwardena et al. 1998b, 2000a, Kyrkos 1997), and that breeding performance tended to improve (Siriwardena et al. 2000b). Long-term demographic trends presented here (see above) show that nest failure rate at the egg stage decreased during the decline and the breeding improvement consequently improved. Cornulier et al. (2009) confirmed that change in breeding frequency was not a cause of decline, as the number of breeding attempts was increasing. As mean laying dates are calculated across all broods, the increase in the number of breeding attempts is also likely to explain why, unlike most other species, the mean date is now later than it was in the 1960s.

Best estimates of the variation in adult and first-year Yellowhammer survival (from ring recoveries) suggest that it has been sufficient to explain the species' decline (Kyrkos 1997). Reductions in winter seed availability as a result of agricultural intensification (for example, the loss of winter stubbles and a reduction in weed densities) are widely believed to have contributed to the population decline, presumably through impacts on survival rates. Siriwardena et al. (2007), found that Yellowhammer declines were less steep in areas where the species received more overwinter provisioning, providing experimental evidence for winter resource limitation. Food availability (and therefore, as a conservation measure, supplementary feeding) in late winter appears to be particularly important because demand for seed food is greatest at this time and this is also when the food supply resulting from agri-environment conservation measures is at its lowest (Siriwardena et al. 2007). Further evidence comes from Gillings et al. (2005), who used two complementary extensive bird surveys undertaken at the same localities in summer and winter to show that the areas of extensive stubble in winter were correlated with better population performance, presumably because overwinter survival is relatively high. This is supported by another study, in Oxfordshire (Wilson et al. 1996), which found that the only habitat type for which a clear preference was displayed in winter was stubble. In Northern Ireland, Colhoun et al. (2017) observed an increase in abundance over five years on farms participating in established agri-environment schemes, but found no direct positive association with the provision of seed rich habitat or any other specific management options. In Wales, experimental provision of ryegrass plots appeared to fill the late winter 'hunger gap' and Yellowhammer body condition was positively related to the amount of ryegrass eaten; however breeding numbers did not change (Johnstone et al. 2019).

In terms of changes to habitat, Kyrkos et al. (1998) found that Yellowhammer breeding density decreased with increasing proportion of farmland under grassland. It may be that modern improved grassland has neither the weed density required by adult Yellowhammers nor sufficient invertebrate prey for birds feeding nestlings. The dense sward structure of highly fertilised leys may also reduce access to invertebrate prey (Perkins et al. 2000). This is supported by the results of Douglas et al. (2010a) who found that foraging in grass margins was increased by experimental mowing, showing that access to prey in dense vegetation limits feeding activity. Siriwardena et al. (2000b, 2000c) provide further evidence that grazing supported the lowest breeding performance, although the best breeding performance was associated with mixed farmland, suggesting that loss of heterogeneity in the landscape may be a factor in the decline, although they state that this is unlikely to be the main mechanism behind the declines. Bradbury & Stoate (2000) further suggest that loss or degradation of hedges and field margins, loss of stubbles and intensification of grassland management may have reduced nest-site and food availability for farmland Yellowhammers.

Increased use of pesticides may have also played a role in decreasing breeding success. Boatman et al. (2004) used an experimental set-up to look at the effect of pesticides on breeding performance, and further evidence was provided by Morris et al. (2005), who showed that increased use of pesticides results in reduced invertebrate abundance, lower brood production and fewer chicks fledging. Hart et al. (2006) also demonstrated how insecticide applications can depress Yellowhammer breeding productivity. Whittingham et al. (2005) found that the local availability of rotational set-aside was a good predictor of sites chosen for breeding territories, which could reflect the benefits of both sparse vegetation (access to bare ground for foraging) and lack of pesticide use. Similarly, McHugh et al. (2016b) found that territories were preferentially located close to enhanced field margins, and suggested that the more open sward structure in these margins may increase prey availability.

Information about conservation actions

The decline from the 1980s is believed to be linked to changes to farming practices resulting from agricultural intensification, with decreased survival believed to be the main cause. Therefore, conservation actions which help improve survival by ensuring additional food is available during winter are most likely to be able to reverse the decline. Food availability in late winter (the 'hunger gap') appears to be a problem for Yellowhammer (Siriwardena et al. 2007) and winter stubble (Gillings et al. 2005; Anderson 2014) and set-aside (Whittingham et al. 2005) are important. As well as the retention of stubble and the provision of set-aside areas, other options which could increase the amount of seed available over winter include the direct provision of supplementary food, the planting of wild bird seed or game cover, and the provision of semi-natural habitats, e.g. through the provision of buffer strips and conservation headlands, and through less intensive farmland management practices. Provision of ryegrass plots helped to fill the 'hunger gap' in Wales (Johnstone et al. 2019).

Although breeding productivity is not believed to be the main driver of decline, some potential issues during the breeding season have been noted and conservation actions which improve breeding performance may also help the recovery. These could include: reducing the usage of pesticides (Boatman et al. 2004; Morris et al. 2005; Hart et al. 2006); and the provision of 'enhanced margins' which provide invertebrate rich herbaceous vegetation adjacent to hedges, such as wild flower mixes, agricultural legumes or nectar plots (Stoate & Szczur 2010; Burgess et al. 2015; McHugh et al. 2016b). Where enhanced margins have not been provided and grass margins are heavily fertilised, mowing of margins may help increase accessibility to invertebrates in dense swards (Perkins et al. 2000; Douglas et al. 2010a).

Note, however, that Dunn et al. (2016) warn that, while land management can promote high densities, breeding success can be reduced by density-dependent effects on provisioning rates, thereby creating an ecological trap. Hence, agri-environment policies should try to ensure that breeding conservation actions are widely applied in order to make them effective.

Publications (3)

Breeding periods of hedgerow-nesting birds in England

Author: Hanmer, H.J. & Leech, D.I.

Published: Spring 2024

Hedgerows form an important semi-natural habitat for birds and other wildlife in English farmland landscapes, in addition to providing other benefits to farming. Hedgerows are currently maintained through annual or multi-annual cutting cycles, the timing of which could have consequences for hedgerow-breeding birds.The aim of this report is to assess the impacts on nesting birds should the duration of the management period be changed, by quantifying the length of the current breeding season for 15 species of songbird likely to nest in farmland hedges. These species are Blackbird, Blackcap, Bullfinch, Chaffinch, Dunnock, Garden Warbler, Goldfinch, Greenfinch, Linnet, Long-tailed Tit, Robin, Song Thrush, Whitethroat, Wren and Yellowhammer.

05.03.24

Reports Research reports

Birds of Conservation Concern Wales 4: the population status of birds in Wales

Author: Johnstone, I.G., Hughes, J., Balmer, D.E., Brenchley, A., Facey, R.J., Lindley, P.J., Noble, D.G. & Taylor, R.C.

Published: 2022

The latest review of the conservation status of birds in Wales. The report assessed all 220 bird species which regularly occur in Wales. There are now 60 species of bird on the Red List, with 91 on the Amber List and just 69 - less than a third of the total number of species - on the Green List.

06.12.22

Reports Birds of Conservation Concern

The State of the UK's Birds 2020

Author: Burns, F., Eaton, M.A., Balmer, D.E., Banks, A., Caldow, R., Donelan, J.L., Douse, A., Duigan, C., Foster, S., Frost, T., Grice, P.V., Hall, C., Hanmer, H.J., Harris, S.J., Johnstone, I., Lindley, P., McCulloch, N., Noble, D.G., Risely, K., Robinson, R.A. & Wotton, S.

Published: 2020

The State of UK’s Birds reports have provided an periodic overview of the status of the UK’s breeding and non-breeding bird species in the UK and its Overseas Territories since 1999. This year’s report highlights the continuing poor fortunes of the UK’s woodland birds, and the huge efforts of BTO volunteers who collect data.

17.12.20

Reports State of Birds in the UK