Pheasant

Introduction

The non-native Pheasant is easily the most common bird roaming the UK countryside and the species most often shot by humans.

The male Pheasant is a handsome long-tailed bird with metallic iridescent plumage. His courtship display, an explosive double pitched bark and vigorous vibrating of wings, is intended to woo multiple brown-coloured females. Sharp spurs on the back of male's legs are used to fight-off would be competitors.

The majority of UK Pheasants are reared for shooting from imported eggs and chicks. Tens of millions are released annually into the countryside where they consume untold numbers of invertebrates and plants. Breeding Bird Survey data show the increase in Pheasant numbers, and only the far north-western corner of Britain escapes its presence.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

Songs and Calls

Call:

Alarm call:

Flight call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

Pheasants have increased steeply in abundance since the 1960s. BBS shows shallow increases in England, Scotland and Wales, and a rapid increase in Northern Ireland, since 1994, with most of these increases occurring during the first ten years of the survey. During 1968-88, a period when the total biomass of birds in Britain fell by an estimated 10%, CBC data indicate that Pheasant biomass rose by about 2,500 tonnes - more than ten times more than any other species (Dolton & Brooke 1999). The increase has been fuelled by a concurrent steep rise in the numbers of Pheasants released onto shooting estates (game-bag data). Numbers have increased across Europe since 1980, again influenced by releases by hunters (PECBMS: PECBMS 2020a>).

Distribution

Following introduction in the 11th century, Pheasants are now widely distributed with the exception of northwest Scotland, and they are scarce on the Outer Hebrides, Skye and Shetland.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

There have been small gains in Pheasant range in the north and west of Scotland, Wales and parts of Ireland, particularly in the west and southwest.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

Seasonality

Pheasants are recorded throughout the year, with obvious cycle of detection: easily seen in spring when displaying, low detection in summer when hidden in crops, and another peak in autumn as birds are released for shooting.

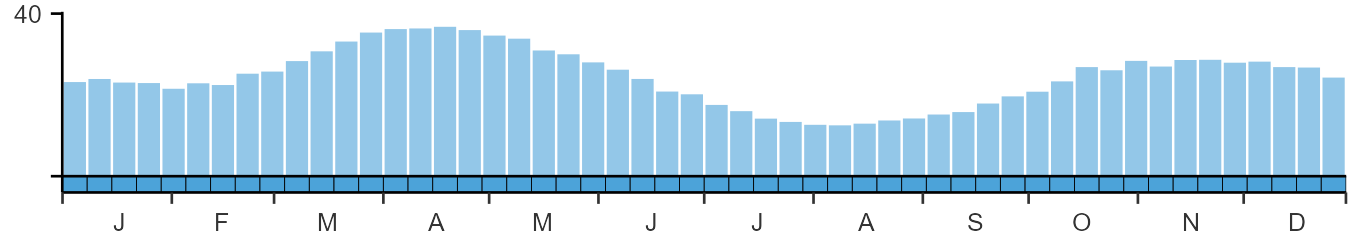

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

Habitats

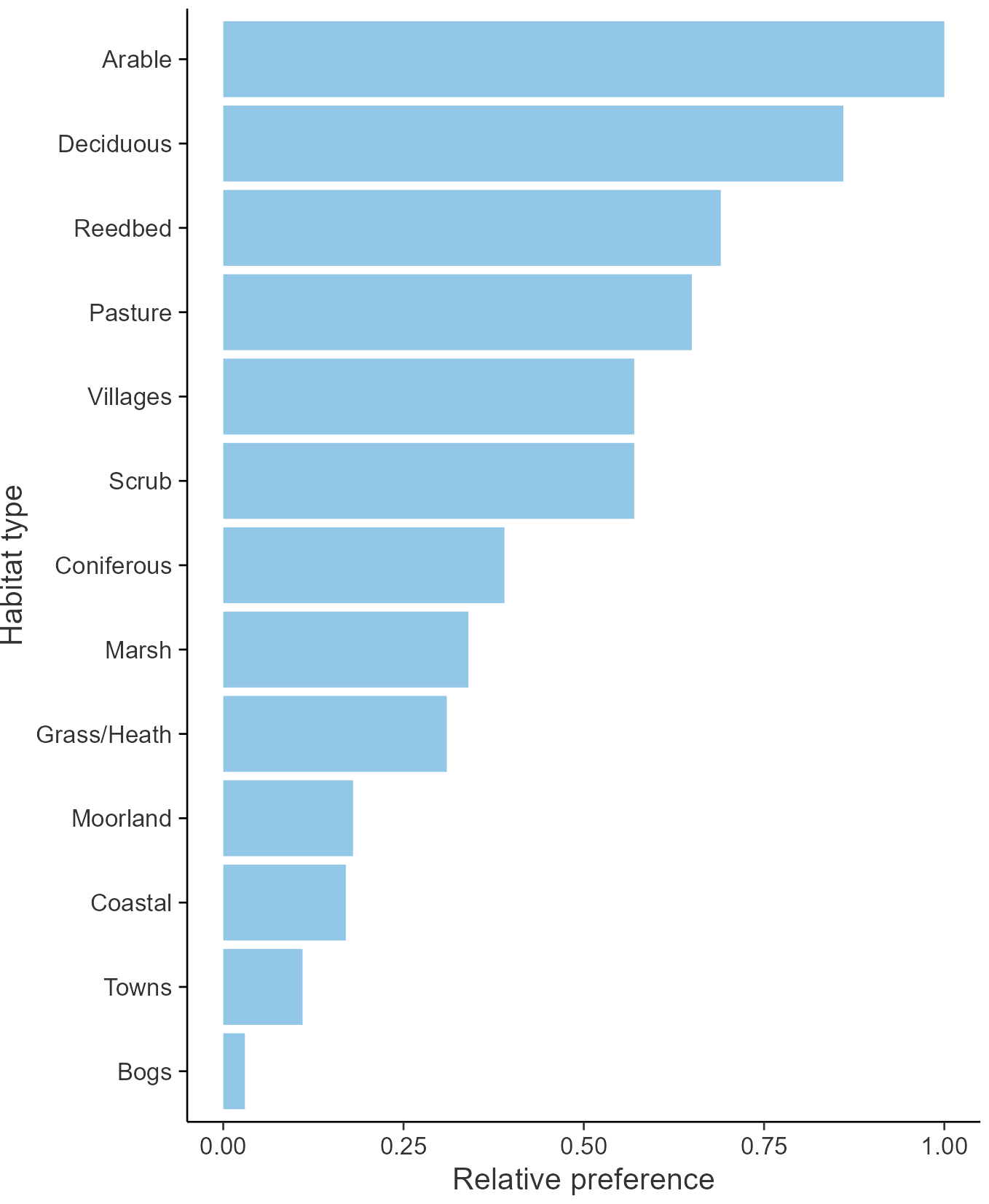

Breeding season habitats

Relative frequency by habitat

The graph shows the habitats occupied in the breeding season, with the most utilised habitats shown at the top. Bars of similar size indicate the species is equally likely to be recorded in those habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

lifespan

Survival of adults

Survival of juveniles

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Galliformes

- Family: Phasianidae

- Scientific name: Phasianus colchicus

- Authority: Linnaeus, 1758

- BTO 2-letter code: PH

- BTO 5-letter code: PHEAS

- Euring code number: 3940

Alternate species names

- Catalan: faisà comú

- Czech: bažant obecný

- Danish: Fasan

- Dutch: Fazant

- Estonian: faasan e. jahifaasan

- Finnish: fasaani

- French: Faisan de Colchide

- Gaelic: Easag

- German: Jagdfasan

- Hungarian: fácán

- Icelandic: Fashani

- Irish: Piasún

- Italian: Fagiano comune

- Latvian: medibu fazans

- Lithuanian: medžiojamasis fazanas

- Norwegian: Fasan

- Polish: bazant (zwyczajny)

- Portuguese: faisão

- Slovak: bažant obycajný

- Slovenian: fazan

- Spanish: Faisán vulgar

- Swedish: fasan

- Welsh: Ffesant

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

The population size of this species is principally determined by releases of reared birds for shooting, which have increased sixfold since 1960. Little is known about the impacts of changes in demographic parameters among wild-breeding birds.

Further information on causes of change

It must be noted that numbers of this introduced gamebird are determined principally by releases of reared birds for shooting (Marchant et al. 1990, Pringle et al. 2019). Such releases increased approximately sixfold between 1960 and 2004 (game-bag data) when around 35 million birds were released annually (PACEC 2006). This has since increased to around 44 million birds in 2012 and 47 million birds in 2016 (Aebischer 2019). Around 35% to 40% of released birds are shot, with the remainder dying from other causes or dispersing away from the release site (Madden et al. 2018, Sage et al. 2018). 'Release efficiency' has declined since 1990, i.e. numbers being released have increased faster than numbers being shot (Robertson et al. 2017). Robertson (1991) studied records of Pheasant nests from the Nest Record Scheme and found that productivity is probably too low to sustain a population. There is little else known about changes in demographic parameters of Pheasants in the UK. However, modelling suggests that climate change may have had a positive impact on the long-term trend for this species, possibly caused by either improved breeding success or increased survival of released birds (Pearce-Higgins & Crick 2019).

Information about conservation actions

As a non-native introduced breeding species, Pheasant does not have a conservation status in the UK.

Large numbers of Pheasants are released annually in the UK, and concerns have been raised that this may impact negatively on the conservation status of some native species. There is evidence that high densities of released Pheasants and Red-legged Partridges may be having a positive effect on some avian predator populations, by providing additional winter food resources and hence reducing winter mortality of predators; this may in turn impact negatively on other UK native birds during subsequent breeding seasons through increased levels of nest predation (Pringle et al. 2019).

High Pheasant densities potentially have other negative effects, which have not been adequately studied, on native UK birds: these include their effect on the structure of the field layer in woodland, the spread of disease and parasites and competition for food (Fuller et al. 2005). Infection with caecal nematodes from farm-reared Pheasants may be contributing to the decline of Grey Partridges in Britain (Tompkins et al. 2000b), although Sage et al. (2002) found that this had no population impact.

Publications (3)

The proportion of common pheasants shot using lead shotgun ammunition in Britain has barely changed over five years of voluntary efforts to switch from lead to non-lead ammunition

Author: Green, R.E., Taggart, M.A., Pain, D.J., Clark, N.A., Cromie, R., Dodd, S.G., Elliot, B., Green, R.M.W., Greenwood, L., Huntley, B., Leslie, R., Porter, R., Price, M., Roberts, J., Robinson, R.A., Smith, K.W., Smith, L., Spencer, J., David Stroud, D. & Thompson, T.

Published: 2025

A full voluntary transition from lead to non-lead shotgun ammunition by 2025 only resulted in a slight, non-significant downward trend in the proportion of Pheasants killed using lead shot over the five-year transition period.

06.03.25

Papers

Supplementary bird feeding as an overlooked contribution to local phosphorus cycles.

Author: Abraham, A., Doughty, C., Plummer, K. & Duvall, E.

Published: 2024

Putting out food for wild birds at garden feeding stations is a common practice, and one of a number of different forms of providing supplementary food to free-living birds. Another is the provision of grain and growers pellets by game managers to support Pheasants and other gamebirds post release. The act of putting out supplementary food may have wider effects on our ecosystems because of the nutrients present in the food, as this piece of research reveals.

07.08.24

Papers

Limited effectiveness of actions intended to achieve a voluntary transition from the use of lead to non-lead shotgun ammunition for hunting in Britain

Author: Green, R.E., Taggart, M.A., Pain, D.J., Clark, N.A., Clewley, L., Cromie, R., Green, R.M.W., Guiu, M., Huntley, B., Huntley, J., Leslie, R., Porter, R., Roberts, J., Robinson, J.A., Robinson, R.A., Sheldon, R., Smith, K.W., Smith, L., Spencer, J. & Stroud, D.

Published: 2023

The SHOT-SWITCH project was set up to monitor the effectiveness of voluntary initiatives to move away from the use of lead shot in game shooting. In the study’s third season, reported here, 94% of Pheasants sampled had been killed using lead ammunition, a slightly but significantly smaller proportion than in the preceding two seasons. There is currently no evidence that voluntary initiatives to promote the replacement of lead with non-lead ammunition by suppliers and retailers of wild-shot game are working.

01.03.23

Papers