Author:

Benedict Macdonald

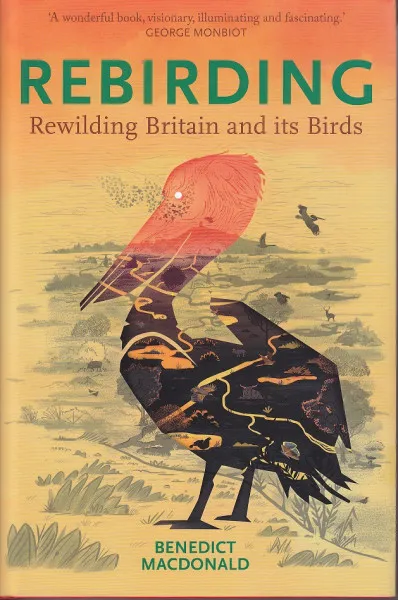

Publisher: Pelagic Publishing, Exeter

One of the few personal joys of these recent challenging months is that I’ve had the time to read many nature books. Some of which have been thrilling reads, and today I thought I would share my thoughts on one of the most revolutionary nature publications in recent times, Rebirding.Rebirding explores how humans have shaped British ecosystems since the end of the last ice age, and how recent farming methods have led to impoverished ecosystems and serious declines in many of our native species. Undeterred however, author Benedict Macdonald presents us with bold new solutions that could bring our threatened wildlife back from the brink. Until the release of Rebirding, Benedict Macdonald was a relatively unknown writer and naturalist, though many would have been aware of his contributions over the years to wildlife magazines such as Birdwatching and Nature’s Home. He also co-produced the Netflix series Our Planet, helping with the script with his knowledge of natural history. Rebirding is his book debut, and I was very much looking forward to reading what visions he has for restoring Britain’s wildlife. Interest in the subject of restoration ecology - or rewilding - has exploded in recent years, with multiple books, such as Feral and Wilding, winning several awards, so I was also wondering whether this book would be as compelling as some of the others. He didn’t disappoint. Rebirding, for the most part, is a fantastic read.What Macdonald has produced here is a gloriously ambitious yet theoretically achievable manifesto to save Britain's wildlife, and he’s done so in a very readable way. The book is extremely thorough, with hundreds of references cited throughout the book, though it doesn’t read like an academic journal. It’s very easy to follow, and I think this will be a fascinating read even to those with just a casual interest in saving nature.The first half of the book focuses more on how Britain once looked in its natural state, and what species it has lost over the last few thousand years. Such species include those that are globally extinct, like mammoths, rhinos and aurochs, and species that exist elsewhere, such as bears, wolves and lynx. For me, reading such passages caused some mixed emotions. On the one hand, sadness that we’ve lost these species, but on the other, the thought of these animals walking around together in the same area made me feel quite tranquil. Macdonald encourages such imagination by often starting chapters with a description of walking around a wildlife-rich landscape which could be in our grasps if we conserve our wildlife properly. Although it does feel a little repetitive, often they make you want to jump into the pages themselves to see such a world yourself. The book is compelling as it is beautiful, and one of the main reasons for this is that Macdonald tells us that much of what we think is right for wildlife, is in fact wrong. I’m sure many of us have a picture of pre-human Britain as being one dense forest, but Macdonald wastes no time in telling us that was simply never the case, and instead, Britain once contained a dynamic mixture of many habitats, such as grasslands, scrub, and open woodlands that were kept in balance by mammalian herbivores. These are the landscapes we should be attempting to restore, and we should not be content with simply planting a load of trees (which often form wildlife deserts).Another example is that, while most of us would think that national parks are havens for wildlife, in reality, a lot are poorly managed for wildlife to thrive. This is also the case for many of our protected sites and nature reserves, which are often over-managed to accommodate only a few species. Yet in such passages he never descends too much into bitter pessimism, and he keeps such chapters light and optimistic by offering slight improvements that could enhance their biodiversity.When talking about what we can do to rescue our wildlife from the brink - which is the main focus of the second half of the book - what repeatedly emerges is that there are many economic incentives to rewilding. A key fact to remember is that only 6% of Britain's surface is built upon, so there is huge scope to change our countryside in ways that could create employment and economic prosperity, and several examples are explored in this book. Such ideas quash the opinion that conservation is an economic burden that hampers progress, and what makes these suggestions so interesting is that a lot of them are based on models and case studies that currently exist elsewhere in Europe in countries with much higher levels of biodiversity. Sometimes it makes you wonder why we haven’t adopted them all this time.The book will of course be a better read for those who are already familiar with the birds found in Britain, but not massively so, as the ecology of a few species that appear repeatedly throughout the book are described in its earlier chapters. Despite its title, this is not solely a book that will appeal to birders. Birds of course are mentioned throughout, but the types of ecosystems that Macdonald is hoping to restore will also be those with higher diversity of other animal groups, such as insects and mammals and reptiles. Birds of course have co-evolved with other faunal groups for millions of years, so naturally optimum habitats for bird communities will also be the optimum habitats for these other groups.For a book of under 300 pages, Rebirding is unusual in having multiple subheadings throughout its chapters. Some of these are better placed than others, but I eventually grew to like them, because one thing that you will struggle to do with this book is to binge-read it. Many of the chapters reveal such bold and thought-provoking ideas that at times you just want to stop at certain points and let them wash over you for a while. That’s how powerful this book is at times.The book isn’t perfect however. Occasionally, I felt that some case studies could have been fleshed out a bit more, especially the Netherlands Oostavaardersplassen project, which is one of the first case studies he talks about in this book. I also felt that Chapter 2, which goes through the changes that Britain has undergone over the past few centuries, felt a bit disjointed, with it not knowing whether to focus on landscape changes over time or on the fortunes of particular species. But these are just small gripes in what is an amazing writing debut.I don’t often comment about the cover of a book, but I think this one deserves some attention. Looking at the habitat in the background, it’s hard to define what sort of landscape you’re in, as you can see wetland species as well as those of woodland and grasslands. But of course, this mosaic of different habitats in one area is exactly what Macdonald is hoping for us to achieve as that’s how it looked before human intervention. But this isn’t a hypothetical landscape; In the background you can see the Burrow Mump, which is a famous landmark of the Somerset levels, so you can see that this is his vision for the region. In the foreground is a transparent ‘ghost’ of a Dalmation Pelican, reminding us that this species was once breeding in Britain, and I think having this famous and charismatic species as the main focus point of the cover was a very good idea. The colours are also impressive. I think the orange and yellow background colour gives an impression of dawn, which is fitting, as the reintroduction of species back into Britain will itself be a new dawn for how we treat our wildlife and landscapes in a sustainable way.Overall, Rebirding is a fantastic book that will likely inspire you to get actively involved in saving Britain's wildlife. This is a read you won’t regret.Book reviewed by Gethin Jenkins-Jones